Alexander Spotswood

Alexander Spotswood | |

|---|---|

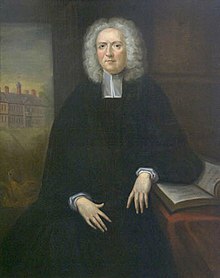

Charles Bridges, Portrait of Alexander Spottswood, 1736. Governor's Palace (Williamsburg, Virginia) | |

| Colonial Lieutenant Governor of Virginia | |

| In office 23 June 1710 – 27 September 1722 | |

| Monarch | Anne – George I (from 1 August 1714) |

| Preceded by | Robert Hunter |

| Succeeded by | Hugh Drysdale |

| Deputy Postmaster General of North America | |

| In office 1730–1739 | |

| Preceded by | John Lloyd |

| Succeeded by | Head Lynch |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 12 December 1676 English Tangier, Morocco |

| Died | 7 June 1740 (aged 63) Annapolis, Province of Maryland |

| Resting place | Temple Farm, Yorktown (?) |

| Spouse |

Anne Brayne (m. 1724) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Great Britain |

| Branch/service | British Army |

| Years of service | 1693–1740 |

| Rank | Major-General |

| Battles/wars | |

Alexander Spotswood (12 December 1676 – 7 June 1740) was a British Army officer, explorer and lieutenant governor of Colonial Virginia; he is regarded as one of the most significant historical figures in British North American colonial history.

After a brilliant but unsatisfactory military career, in 1710 he was nominated colonial governor of Virginia, a post which he held for twelve years. During that period, Spotswood engaged in the exploration of the territories beyond the western border, of which he was the first to see the economic potentials. In 1716 he organised and led an expedition west of the mountains, known as Knights of the Golden Horseshoe Expedition, with which he established the Crown's dominion over the territory between the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Shenandoah Valley, thus taking a decisive step for the future British expansion to the West.

As the governor of Virginia, Spotswood's first preoccupation was to make sea routes safe and fight against the pirates. After a long effort, the famous pirate Blackbeard was hunted down and killed in 1718. In addition, Spotswood promoted the economic growth of the colony by founding the metallurgical settlements of Germanna; introduced the juridical instrument of habeas corpus; and introduced the rules for the commercial relations with Native Americans and those for the tobacco export trade. His tenure was characterised by a growing conflict with the Virginian political classes, which ended with his removal from office.

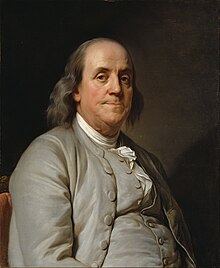

Years later, between 1730 and 1739, Spotswood was Postmaster General for British America and, with his young friend Benjamin Franklin, extended the postal service network north of Williamsburg and improved its efficiency.

At the outbreak of the War of Jenkins' Ear, Spotswood was called back into army service. Promoted to major general, he was put in command of the colonial troops stationed in America with the task of preparing a military action against the Spanish stronghold of Cartagena de Indias, but, in Annapolis, where he was to consult with the local governors, he died suddenly in 1740.

Origins and youth

[edit]

Alexander Spotswood was born in Tangier, a city on the African shore of the Strait of Gibraltar, in 1676. At that time the city, under English occupation, was run by a local governor and housed a garrison, where Spotswood's father, Robert, practiced as surgeon,[1] first as surgeon George Elliott's assistant, succeeding him when he died and marrying his widow, Catharine Maxwell, who gave him an only son, Alexander. Alexander's older half-brother (by his mother's first marriage to George Elliott) was Roger Elliott, who became one of the first governors of Gibraltar.[2]

Both parents had Scottish origins, and the father, although economically ruined, could boast an illustrious lineage. His family had ancient baronial origins and had enjoyed great prestige until the time of the English revolution. There had been illustrious Spotswoods, such as judge Robert Spottiswoode (Alexander's grandfather) and Archbishop John Spottiswoode.[3]

In 1684, following attacks of native Berber troops under the guide of governor Ali ben Abdallah, the city of Tangier was evacuated and the Spotswood family returned to England, where the father died in 1688. In May 1693, at the age of sixteen, Spotswood enlisted in the English Army, the army of the Kingdom of England, with the rank of Ensign in the Earl of Bath's Regiment of Foot. He served first in Ireland and then in the Flanders. Over the years, distinguishing himself for skill, courage and intelligence, he climbed the military hierarchy to the rank of lieutenant colonel.[1]

First army experience

[edit]The War of Spanish Succession broke out in 1701. The main European powers fought each other throughout the following decade. John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, was in command of the English army stationed in central Europe. Alexander Spotswood was part of it as deputy quartermaster general. The troops remained quartered along the River Rhine for three years for the protection of the Netherlands. Marlborough's army descended into Bavaria In 1704, taking the Franco-Bavarian forces by surprise. The Battle of Blenheim took place on August 13 and ended in a major British victory. During the battle Spotswood was severely wounded in the chest during a heavy artillery attack. Medicated on the battlefield, he was then sent to London to convalesce. He survived the and kept the cannonball, which he used to show his friends and guests.[4]

He returned to the Flanders almost two years later. On 11 July 1708 he fought in the Battle of Oudenaarde, in the Netherlands, where his horse was killed and he fell prisoner to the French troops. But Duke of Marlborough, once again the winner of the battle, obtained his release by negotiating personally with the enemy, and Spotswood returned to his duties as quartermaster general to oversee the corn supply for the troops.

However, his disappointment for the slowdown of his military career was growing. Despite the good relationship with and the trust of his superiors, he was stuck in the rank of lieutenant colonel. His ambitions, fuelled by the many but never kept promises of promotion, were continuously frustrated. In September 1709, having spent half of his life in the army, he took his leave and returned to London.[4]

Governor of Virginia

[edit]

During the war, Spotswood had made good friends not only with the Duke of Marlborough, but also with another of his commanders, George Hamilton, 1st Earl of Orkney.[1] Hamilton had held the post of governor of the colony of Virginia from 1704, but resided in London and was represented on American soil by a plenipotentiary delegate, with a nominal mandate as deputy governor. In 1707 the deputy governor, Robert Hunter, had been captured by the French at sea and the colony was thus temporarily administered by a local government.[5] At the suggestion of Hamilton himself, with perhaps an additional push by Marlborough, on February 18, 1710 Queen Anne appointed Spotswood as vice governor of Virginia. On April 3, Spotswood left for the Americas from the port of Spithead, in southern England, aboard the man-of-war HMS Deptford, in convoy with other British ships to ward off pirate attacks.[6]

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, Virginia was the most prosperous and populous of the Thirteen Colonies. The inhabitants numbered around 80,000, including 20,000 slaves – most of them from the Bight of Biafra – employed in the vast tobacco plantations, at the service of a confederation of landowners.[7] The export of tobacco was still one of the most lucrative activities, but in recent times, due to the war against the French and the consequent closure of the Atlantic trade routes, it was not as rewarding as in the past, and overproduction had caused prices to drop. In addition, in a period considered the golden age of piracy, the southern waters of British America were swarming with pirates and corsairs. Coming from the Caribbean Sea, they sailed northwards along the American coastline as far as Virginia, making harmful raids. Moreover, the land borders of the colony were at that time threatened by the aggressive behaviour of numerous Native American tribes.[8]

Arrival at the colony

[edit]After ten weeks of good navigation, the convoy arrived in Virginia on June 20, and landed at the Hampton Roads bay (then known as Kecoughtan, the local Algonquian name).[6] Three days later, Spotswood was in Williamsburg, the capital of the colony, where he was sworn in as governor, in the newly built Capitol.[9] The Virginians gave him an enthusiastic welcome, both because he was the first governor present on the territory after four vacant years, and because he brought with him a royal decree that extended to colonial citizens the right of habeas corpus, granted to the subjects in England since the time of the Bill of Rights of 1689.[10]

For the previous four years the colony had been ruled by the twelve members of the Governor's Council, who were appointed by the King. Just like the fifty representatives of the House of Burgesses (who were elected by their Virginian peers), they belonged to the class of the great landowners whose real aim was to establish a de facto oligarchy.[11] Their interests often clashed with those of the Crown, and in the oversea territories their interests generally prevailed.[12] On July 5 Spotswood made his first encounter with this problem. A resolution passed by the Governor's Council prior to his arrival had abolished the application of the annual payments for the tobacco lease and established the principle that tobacco be exchanged at a public sale. Now, considering the low revenues, the Crown had decided to return to the old method of trade, but the Governor's Council, whose members controlled the public sale of tobacco, refused to implement the new rule. Spotswood favoured the council's opinion, and this was the first public conflict of interests between the Crown, of which Spotswood would be for years to come a staunch supporter, and the wishes of the local ruling classes.[13]

On October 26 of the same year began a long meeting of the House of Burgesses and the Governor's Council – the first since 1706 – during which Spotswood listed some points in the program he intended to implement, namely,: to strengthen the military defence of the colony; to keep down the number of slaves escaping from the plantations; to extend the postal service; to complete the construction of the Governor's Palace in Williamsburg. In addition, following the Crown's suggestions, he proposed to rebuild the College of William and Mary which had been destroyed by a fire five years earlier, and to establish a court of oyer and terminer (a sort of superior criminal court) that would have to meet every six months.[14]

Threats at the borders

[edit]Meanwhile, another pressing issue reawakened his military vocation. A colonial militia of about 15,000 men was deployed to protect the land borders. The majority of the troop came from the lower labouring classes, were poorly armed and operated under the orders of inexperienced commanders.[12] Since his arrival in Virginia, Spotswood had shown concern about the colony's vulnerability and had started to reorganise and strengthen the militia to match the task of defending the colony.[15] During the summer of 1711, he personally supervised the installation of a series of cannons in the ports between Yorktown and Jamestown to prevent a possible French naval invasion.[16]

In September 1711, the Tuscarora, an Indian nation whose territories extended from Virginia to the heart of North Carolina,[17] engaged in an extended period of conflict with the settlers for commercial and border protection reasons and, during a series of attacks on settlements and plantations on the Carolina-Virginia border, killed hundreds of colonists.[18] That was the beginning of the so-called Tuscarora War. Spotswood, well aware that it was a real war, considering how badly equipped the militia was, requested weapons and ammunition from England, which however would take a few months to arrive. His aim being to prevent other tribes from joining the Tuscarora revolt, he headed south with the 15,000 militia men and stopped on the bank of the Nottoway River. The local tribes proved to be well disposed towards the British and offered them military support against the Tuscarora. As a guarantee, Spotswood demanded that each tribe deliver two of the young sons of the tribal chiefs as hostages, to be educated in Williamsburg at the William and Mary's College. The objective was twofold: to give them a Christian education, so that they could return later as missionaries to their own tribes – within the framework of a wider operation to civilise the Indians –, and at the same time to guarantee for a certain period of time the friendship of those tribes.[19]

In early December, hostages from several tribes arrived in Williamsburg. The House of Burgesses, however, was not happy about this resolution, as they would have liked a more direct military action against the Indians. Spotswood argued that a field operation could not be sustained and that his initiatives were, for the time being, "a sober way of waging war." However, an amount of £20,000 was set aside to wage war against the Tuscarora, and discussions carried on until Christmas, when Spotswood dissolved the assembly.[20] Between the summer and the fall of the following year, some of the rebel Tuscarora chiefs were captured and transferred to North Carolina for trial.[21]

Contrasts with the House of Burgesses

[edit]The War of Spanish Succession ended in April 1713, and the British victory led to the reopening of the Atlantic trade routes and the annexation of new colonies. The Virginian economy was revitalised, and in particular the tobacco export trade which in recent years had been severely affected by the conflict.[22] Tobacco in those days was also used as a means of payment and was sold by the weight. To make more profit traders often added poor quality to high-quality varieties, causing prices to drop. Previous colonial governments had made attempts on several occasions to regulate the trade, but nothing had ever really come of it.[23]

So, in November 1713, Spotswood, to bring the tobacco market under control and set limits to the practices of the big landowners, submitted to the House of Burgesses the Tobacco Inspection Act. The new law, supported by the Governor's Council, required tobacco to be inspected before shipment to Europe. In Spotswood's intentions there would thus be a reduction in the quantities exported, resulting in an increase in the quality of the goods and a consequent increase in demand and in price.[24] To soften the opposition of the House of Burgesses', Spotswood appointed as inspectors some of the representatives in favour of his proposal, which was finally approved. The reform, however, produced only partial results compared with the expectations: prices did not rise immediately, and the inspection procedure was disliked by the landowners.[4][25]

Yet another initiative by Spotswood caused him to lose the favour of the Virginian elite. In December 1714, he had the Indian Trade Act passed. All commercial activities with the Indians south of the James River were placed under the exclusive control of the Virginia Indian Company, established with an allocation of £10,000.[26] The measure should have put an end to the illegal trade that took place along the border and which, according to Spotswood, was one of the reasons for the unrest of the Indians, and at the same time was against the interests of the colonials who were trading privately with the Indian tribes.[27] William Byrd II, an influential member of the Governor's Council who wanted Spotswood's position for himself, was in control of much of the trade with the Indians, particularly the Cherokee, to whom he sold cloth and weapons. Shortly after the law was passed, Byrd left for England on personal business, but certainly also with the intention of bringing Spotswood discredit in the various branches of the royal administration.[28][29]

The disputes between Spotswood and the members of the House of Burgesses grew until they degenerated in 1715. During an assembly held between August and September the representatives, instead of concentrating on the problems of the colony's defence as was Spotswood's recommendation, challenged the Indian Trade Act and the Tobacco Inspection Act. The discontent generated by the latter among landowners and merchants had played a fundamental role in the last elections of the House of Burgesses. Almost all the representatives who had previously supported the act had lost their seat, and a large section of the newly elected were in disagreement.[4] The scarce rainfall of the previous year had provided the tobacco traders with reasons to justify the request of being allowed to sell all the tobacco produced, regardless of its quality, ignoring therefore the provisions of the Tobacco Inspection Act.[30]

After five weeks of time-wasting discussions – which irritated him all the more now that some Indian tribes at the border were becoming hostile, putting the application of the Indian Trade Act at risk –,[31] Spotswood put an end to the debates and closed the assembly.[32] It was not so much the closing of the Assembly that intensified the hostility of the representatives against the governor, it was rather his definition of the House of Burgesses as "a Set of Representatives, whom Heaven has not generally endowed with the Ordinary Qualifications requisite to Legislators".[4][33] In early 1716, an anonymous letter from Virginia to the London Board of Trade denounced Spotswood for alleged violations of the law, even more strongly than previous still anonymous letters,[34] and accused him of greed and tyranny.[35]

First explorations of the western frontier

[edit]Despite the contrasts with the House of Burgesses, during the middle years of his tenure, Spotswood concentrated mainly on the exploration beyond the western frontier, beyond the foothills of Piedmont.[36] On account of the Tuscarora war, the situation at the border had become tense again, but after one hundred years of periods of war followed by periods of peace, the British and the Indians had learned that, in the absence of a winner, they had better try and live together.[37] To deal with the Indian threat, since his arrival in Virginia Spotswood had sent rangers to patrol the border and explorers in search of a pass through the Blue Ridge Mountains.[38] In the spring of 1714, he personally joined an expedition to explore the upper reaches of the York and Mattaponi Rivers.[39] These explorations took place for precise strategic purposes. The French had long been trying to open a connection between their colonies in New France and the forts along the Mississippi River; their possible success – which Spotswood believed imminent – would soon cut off the British from the interior of the region, based as they were along the coast near the mouth of the James River.[40]

In the summer of 1714, having sufficiently secured the borders, Spotswood went into action by establishing two forest settlements beyond the Tidewater border, which for the past century had signed the limit of British expansion.[41] The first settlement, Fort Christanna, stood on the southern bank of the Meherrin River, near the border with North Carolina. Built for the headquarters of the Virginia Indian Company, the company created under the Indian Trade Act, the fort housed a school for the education of Indians to the Christian way of life.[42] Spotswood's objectives, in addition to those of immediate strategic utility already pursued at the time of the Tuscarora war, were ambitious: to turn the traditionally semi-nomadic Indians into a resident population.[39]

The second settlement established by Spotswood was Germanna, situated north of a bend of the Rapidan River. A group of refugees from the Palatinate,[27] arrived in America in 1709 with the approval of Queen Anne following the destruction of their lands during the War of Spanish Succession,[43] had settled in the region and they had discovered deposits of silver and iron. Initially, nine families of German Protestants settled in Germanna, working for the local smelting furnaces.[44]

In October 1714, news came that Queen Anne had died in early August.[26] During the assembly of the House of Burgesses following the event, Spotswood proclaimed the new king, George I of Great Britain, and claimed the results obtained during the summer: the frontier had been secured; the economy was improving and the defence costs had been reduced thanks to the building of Fort Christanna, which made it easier to control the Indians by concentrating their commercial interests in a single area, and thanks to Germanna, where mining was already a profitable activity.[45]

Knights of the golden horseshoe expedition

[edit]

1716 saw the results of the previous explorations in the western territories. On June 12, Spotswood reported to the Governor's Council that some rangers had found a passage through the mountains and offered himself to lead an expedition beyond Piedmont, in regions then unknown. The Council approved the proposal, on the consideration of its commercial and strategic potential.[46]

Spotswood left Williamsburg with a few men on August 20, 1716, and headed for Germanna, where a meeting point had been fixed. Here the expeditionary force was formed, and on 29 August a group of sixty-three men set off for the mountains. The group included influential members of the settlers' community, servants, rangers, native guides and a good number of horses and dogs.[47] The group went up the Rapidan River, hunting animals and toasting the new king, through a dense bushy area crossed by numerous water streams. During the march, some men contracted measles and were left behind in a field hospital readily set up and manned by rangers. The rest of the group proceeded under the threats of bears and rattlesnakes, until they reached the source of the Rapidan River on the Blue Ridge Mountains, on 5 September.[48]

They crossed the mountains passing through a gorge by the name of Swift Run Gap at an altitude of 720 m, bordered by two mountain peaks. Spotswood named George the higher of the two in honour of the king, and his companions named the other Alexander in his honour.[49] They descended from the ridge towards the Shenandoah Valley: the first Westerners to set eyes and foot on it.[50] Crossing woods and meadows populated by elks and buffalos, after about ten kilometres they reached the bottom of the valley and the course of the Shenandoah River, which was renamed Euphrates.[51] Gun shots were fired here in honour of the king and a great toast was held.[52] Spotswood engraved the king's name on a rock and in an empty wine bottle introduced a card containing the British claim on the river and its territory. The bottle was buried in the riverbank.[53][54]

On September 7, the company left for Germanna, and in ten days was back in Williamsburg. The following winter, Spotswood gave each member of the expedition a miniature gold horseshoe with engraved in Latin: Sic juvat transcendere montes ("This is the way to cross the mountains").[55]

Since then, the expedition was also known as "Knights of the Golden Horseshoe Expedition" and described by Spotswood's biographer, Walter Havighurst, as "the most romantic episode in the history of Virginia".[47] It played a leading historical role not so much for the practical results it achieved, but for the impulse and the inspiration it provided for those who later wanted to venture in the exploration of the interior of the American colonies.[56]

The expedition also left considerable traces in American literature. A few months after the company's return, a humanities professor at William and Mary's College, Arthur Blackamore wrote a short poem in Latin celebrating the expedition: Expeditio Ultramontana. The original Latin text, considered to be among the best examples of Latin poetry in 18th century America, has been lost, but the English version that George Seagood produced in 1729 survives in its entirety.[57]

Over a century later, in 1835, William Alexander Caruthers published a chivalric novel, The Knights of the Golden Horse-Shoe, telling a somewhat revisited history of the expedition.[58][59] In the 20th century, the poet Gertrude Claytor wrote a commemorative poem of the Golden Horseshoe Expedition. Engraved on a bronze plaque, in 1934 it was posted near Swift Run Gap.[60]

Opposition in London and in Williamsburg

[edit]The success of the Transmontane Expedition was welcomed in the London administrative offices, but in less than a year a severe blow to the Spotswood's peace of mind came from the capital.[61]

At the beginning of the year 1717, a large group of influential London merchants wrote a letter to the Board of Trade declaring that the legislation promoted by Spotswood harmed the commercial interests of both the motherland and Virginia itself. The merchants reported that, due to the corruption of the inspectors by the landowners, the lower quality production was not only still on the market – in contradiction with the purposes of the Tobacco Inspection Act – but had actually overtaken the higher quality varieties. The Virginia Indian Company's monopoly on trade with Indians also deprived the merchants of a lucrative market, and this, coupled with heavy export regulations, made their activities unprofitable. The merchants therefore asked for the abolition of those laws which they considered an obstacle to the development of trade. The king thus put a veto on the Tobacco Inspection Act and on the Indian Trade Act, and Spotswood was forced to revoke both. William Byrd, in a letter from England to Philip Ludwell, a member of the Governor's Council, wrote that he had contributed to the abrogation of those laws and to the weakening of the position and influence of the governor.[62]

The House of Burgesses opposed public funding of Fort Christanna, which had to be dismantled as a consequence, although Spotswood feared that this would destabilise the border, leaving local Indian tribes without British support and at the mercy of the Carolina tribes. This put an end to the Indian Trade Act, but not to the principles it sought to implement, which remained central in Spotswood's policy for years to come.[63] As for the Tobacco Inspection Act, on the other hand, years later, in 1730, the same measures were successfully re-proposed and did not meet as strong an opposition as previously.[64] In all probability, the hostility of the House of Burgesses, rather than to a genuine intention to favour trade, was due to its tendency to oppose the actions of the governor, who had been fighting for years with the representatives for the effective control of the colony.[65]

During this period of time, in addition to William Byrd's mission to London, other members of the Governor's Council were openly taking position against Spotswood. The most determined among them was the Reverend James Blair, delegate of the Bishop of London and president of the College of William and Mary, one of the most powerful men in the colony, who had already been behind the dismissal of past governors Edmund Andros and Francis Nicholson.[66] The reason for this opposition was once again to be found in the resistance, on the part of the Virginians, to royal prerogatives affirmed by Spotswood, who claimed for the governor the right to appoint judges in criminal trials (through procedures called oyer and terminer). The members of the council, on the other hand, claimed to be the only ones entitled to do so.[67]

In any case, the Virginian popular opinion supported the governor, who was particularly popular with the small landowners, the yeomen class. And, despite Byrd's scheming against him in London and the revocation of his laws, Spotswood still enjoyed the protection of the King's ministers and of the members of the Board of Trade.[68]

Of pirates and Indians

[edit]In a letter sent in August 1717 to Secretary of State Joseph Addison, Spotswood reported that the only sources of concern left to impair the peace and quiet of the colony were piracy and the aggressive nature of the Indians.[69] Just a few months earlier, several armed Seneca gangs had moved from the Province of New York to the Virginia border, where they had engaged in raids and robberies.[70]

In March 1717, some chiefs of the Catawba tribe had gone to Fort Christanna to discuss a trade treaty with the British and Spotswood, who had long-awaited the good disposition of the Indians, had joined them. In the days of the meeting an episode took place which risked compromising the negotiations. One night, some Seneca or Mohawk Indians – enemies of the Catawba – entered the fort, where the governor was lying asleep, and killed some members of the delegation, who were not bearing arms as Spotswood had imposed. Others were kidnapped. Initially, the Catawba accused the British of having betrayed them and started to leave, but Spotswood, who was in danger of seeing his plans to secure the border undermined, sent a contingent to recover the abducted, reaffirmed his friendship with the Indians, and promised them greater protection. In the end, the Catawba agreed to trade at Fort Christanna and leave some of their children there to study, and the border situation seemed to improve, at least temporarily.[69][71]

The other looming threat were the pirates, who attacked ports and robbed ships, greatly hampering trade. The most famous and feared among them, Edward Teach, who went down in history as Blackbeard, had recently returned to sail the seas, having received the King's pardon and having later surrendered to the governor of North Carolina, Charles Eden, who was probably in cahoots with him.[72] When Blackbeard attacked a convoy of ships in front of Charleston Harbor in May 1718, looting and taking prisoners, the Carolina residents sought help from neighbouring Virginia.[34] Although he did not have a specific mandate from the king – which was necessary for the arrest and trial of pirates –, Spotswood decided to intervene, wary of Carolina's possibilities of dealing with the problem.[73] He quickly had former Queen Anne's Revenge quartermaster William Howard arrested, who had apparently retired from piracy and lived in Virginia, suspecting that he was still in contact with Blackbeard. From Howard, later pardoned, he learned that Blackbeard was with a few men in one of his usual shelters, the Ocracoke Inlet.[74]

Ocracoke was in North Carolina, out of his jurisdiction, but Spotswood was now determined to capture the pirate as quickly as possible, dead or alive, even by violating the sovereignty of another colony.[75] So, without waiting for the authorization of the House of Burgesses, he sent two warships against Blackbeard under the command of Navy Lieutenant Robert Maynard. On November 22, 1718, after five days of search, the pirates were taken by surprise. Maynard, aboard HMS Pearl, attacked Blackbeard's ship, who was killed in a short and bloody fight. Nine of his men died with him, and Maynard lost a dozen of his men.[76] Two days later, Maynard returned to Jamestown with fifteen prisoners, who were later hanged, and Blackbeard's severed head was stuck on the tip of the bowsprit.[77]

Home politics: towards a truce

[edit]The apparent quiet at the borders was the background of new conflicts within the colony. Spotswood soon faced sharp criticism from the House of Burgesses for his moves against the pirates, and when a dispute arose between Spotswood and Eden, the governor of North Carolina, over the legality of the arrest and killing of Blackbeard and his crew (they happened to be under the jurisdiction of North Carolina). Some members of the House of Burgesses published a controversial pamphlet in which they reported of illegal proceedings on the part of Spotswood and in particular of the lack of prior consultation with Governor Eden. It appears that Spotswood was highly likely aware of Eden's political weaknesses and of his compromises with the pirates, and that he purposely omitted to seek his cooperation.[78]

At the same time, relations with the Governor's Council also reached a critical point. In the early months of 1719, with the dispute over the pirates unresolved, a hard dispute arose over the powers of some sectors of the Church.[79] Led by James Blair and other members of the council, a first group was in favour of the current law which provided for the clergy to be directly appointed by an assembly of parishioners and without the approval of the governor. This law, which made the position of individual clergymen uncertain and dependent on the mood of parish assemblies, prompted a large part of the Virginia clergy to support Spotswood in his efforts to modify the law and give the governor, as the King's representative, the power to assign the clerical positions.[80] Both sides turned to the Bishop of London, accusing each other of interference and abuse of power.[81] The Bishop of London then called for an assembly of all the clergymen of Virginia to take place in Williamsburg in April at the William and Mary's College, in the presence of Blair and Spotswood.[82] Since the assembly failed to reach a decision, the situation remained unchanged and thus Blair was the winner of the contest[83]

This growing hostility of the council had already manifested itself during the previous year and Spotswood, unable to bring it under control, had tried to change its composition. In November 1718, he asked the Board of Trade to remove some advisers hostile to him, including Blair and Byrd, who was still in London, and to replace them with men he trusted.[84] The Board of Trade did not fully comply with Spotswood's requests: only two of the men he proposed were appointed and the only councillor removed, Byrd – who returned to Virginia early in 1720 – was almost immediately reinstated.[85]

1720 was the year of a change. Unable to get rid of them, the governor tried to make peace with the members of the council. Byrd, who was now resident in Virginia and could therefore be more easily controlled, became Spotswood's point of reference. The two met at the Capitol and resolved to cooperate. On April 29, 1720, during the next assembly of the council, the governor and the councillors officially declared their resolve to work in harmony from then on.[86] In this more relaxed situation, Spotswood obtained land concessions near Germanna and the western frontier, for a total of approximately 86,000 acres, where he began to build his private residence.[4] The Spotswood estate formed the core of the Spotsylvania County, which was established in 1720 in his honour.[87]

Meanwhile, the buildings of the Governor's Palace and of the Bruton Parish Church in Williamsburg, which Spotswood had personally collaborated to design, were completed. The Governor's palace, in particular, was the subject of criticism for its pomp and excessive costs, but its architecture was appreciated, so much so that in its time it became a model for all residences of prestige.[88]

The truce made official in 1720, although sincerely wanted by the parties involved, appears as a prelude to the final attack against Spotswood. During the summer of the following year, Byrd and Blair left for England, there to reiterate more forcefully their efforts against the governor.[4][29][89]

Last years of government

[edit]

Despite the territorial expansion established with the Expedition over the mountains, Spotswood deemed it necessary for Great Britain to expand further northwest, as far as the Great Lakes, to gain strategic advantage in view of an imminent war against the French. He had already obtained an accurate map of the entire western area of the Mississippi River System, hitherto virtually unknown to the British, to be used for an expedition to Lake Erie, where Spotswood intended to establish a settlement.[90] In February 1720, Spotswood proposed to go on a secret mission to London to present these ideas to the government and to illustrate in detail how it was possible and necessary to conquer Spanish Florida by attacking the Spaniards in St. Augustine, in order to prevent the French fleet from entering the waters of the Thirteen colonies from the Gulf of Mexico.[91][92]

The secret missions never took place, and Spotswood, during his last two years as governor, concentrated instead on resolving the Indian question. If piracy was in rapid decline after Blackbeard's death, the problems caused by the hostile and bellicose Indian tribes were increasingly worrying.[93] The first outbreak was on the Maryland border, and was fuelled by hostilities between the neighbouring tribes and those of Virginia. In the fall of 1720, tribes from Maryland attacked plantations in the Northern Neck, whereupon Spotswood, with the support of the governor of Maryland, called a meeting with the ambassadors of the five Iroquois Confederation tribes who were in conflict with the Virginia Indians.[94] During the meeting, which took place in Williamsburg in October 1721, three of the five ambassadors died, possibly poisoned. Despite this event, of which the Iroquois suspected the Virginia Indians, an agreement was reached by which the Potomac River became the frontier between the Indians of Virginia and the Iroquois, and no Indian was to cross it without the authorization of the British.[95]

Encouraged by the results, Spotswood began organizing a general meeting with the Iroquois tribes and their Sachems (supreme leaders), with the collaboration with the governors of Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New York.[95][96] By June 1722, the time was ripe for Spotswood to sail from Virginia with one delegate from the Governor's Council and one from the House of Burgesses, and many gifts for the Iroquois from the Virginia Indians and from the colony's government. He set sail for New York and from there, along with Pennsylvania governor William Keith and some New York government spokesmen, he left by land for the city of Albany, located on the banks of the Hudson River.[97]

The delegation, which arrived in Albany on August 20, was the most representative the British had ever set up in the Thirteen Colonies, and their commitment must have impressed the Indians. Within a few days they were joined by the leaders and warriors of the Mohicans, Oneida, Cayuga, Onondaga, and Seneca; practically all the nations in the Iroquois Confederation, followed later by the Powhatans and other tribes from Virginia. On August 29 the conference began, and Spotswood gave the inaugural address, during which he expressed hope for the continuing collaboration between the British and the Indians and reaffirmed that the Virginia tribes had had nothing to do with the death of the three Iroquois ambassadors in Williamsburg a few months earlier. He gave the Indian Chiefs pearl necklaces as a gift to demonstrate British good will. Then he asked officially for confirmation of their commitment of the previous year to put an end to the raids in Piedmont and to respect the natural boundaries of the Blue Ridge Mountains and of the Potomac River. The Indians took about ten days to answer, then the agreement, which was Spotswood's main objective, was ratified.[98][99]

On 12 September, the conference ended. During the farewell ceremony with the Indian leaders, Spotswood made a gesture of high symbolic value: he detached from the collar of his jacket a gold pin in the shape of a miniature horseshoe, like the one he had given to his companions for the Transmontane Expedition, which he used to wear as a good luck charm, and gave it to the Iroquois sachems, explaining that they could use it as a pass to go on a mission to Williamsburg. Spotswood also made a personal gift to the Indians of fine fabrics and work tools. Then he left by ship along the Hudson River, heading for the open sea.[100]

Removal from office

[edit]When he arrived in Williamsburg, Spotswood learned that, despite the popular support he enjoyed, the king had decided to revoke his position as governor.[101] On September 25, with Spotswood back in Williamsburg, James Blair, who had been absent for the past 12 months, and the new governor, Hugh Drysdale, an Irishman, arrived in the New World on the same ship. The Drysdale nomination, dated April 3, 1722, was made official and Drysdale was sworn in as governor on September 27.[100]

Historians are in disaccord when explaining the reasons behind the removal of Spotswood from office. Walter Havighurst identified Spotswood's character as main cause; a strong, sharp, and sometimes authoritarian character, prone to the regime of obedience in the military tradition, which the Virginia aristocracy was neither used to nor willing to accept.[102] In fact, during the twelve years at the helm in Virginia, the governor ended up into a conflict with each one of the strong powers of the colony, as well as with the more influential of his own men, from merchants to large landowners. The causes of his removal, which are never explicitly expressed in the official documents of the time, must be sought, according to Havighurst, in the controversy over the oyer and terminer courts, or over the more recent controversy on the clergymen's appointment.[103] However, the overall policy adopted by Spotswood was inevitably destined to enter into conflict with the political class of Virginia, representative of landowners and merchants interests, whose dominance and political interference Spotswood sought to stem, in particularly James Blair's and William Byrd's, who had the means, in terms of both power and influence, to overthrow a governor.[104]

The evaluations of Spotswood's contemporaries were also discordant. Harsh criticisms of some aspects of his work can be found in the writings of James Blair and William Byrd, whose letters have been preserved. Equally high praise, however, can be found in Robert Beverley (see his History and Present State of Virginia), who was one of the first historians born in Virginia, as well as Spotswood's companion in the Transmontane Expedition. Another Spotswood's political ally, Hugh Jones, professor at William and Mary's College, wrote in 1724, (The Present State of Virginia), that Virginia had become more civilised in the twelve years of Spotswood's tenure than in the previous one hundred years.[105]

Among modern historians prevails a generally positive opinion about the Spotswood administration: brilliant and significant in its character; a strong guide in a period of economic growth and cultural development.[4][106] Historian John Fiske, in the late nineteenth century, described Spotswood as one of the best and most capable governors of the British colonial period in America and praised him in particular for the founding of the Germanna smelting plant and for the audacity of the Transmontane Expedition.[107] The same opinion was expressed by historian Virginius Dabney, who described Spotswood as the most celebrated among the governors of Virginia during the colonial period.[108]

Between Virginia and England

[edit]After the experience of government, Spotswood moved to his private residence situated along the Rappahannock River, near Germanna, where he devoted himself to the administration of his large estate and to the management of his metallurgical enterprise. Part of the production of iron and cast iron was exported to England and the rest was destined to the local market. For the other activities, mining and agriculture, Spotswood made use at first of the Palatine refugees he had introduced in Germanna almost ten years earlier, and when the contract that bound them to him expired, he resorted to slaves from Africa. Spotswood's activities also included raising livestock, producing naval supplies, pitch, tar, and turpentine.[87]

However, having assigned land to himself in large quantities during his tenure as governor, he was accused in some circles of land grabbing. So, with the intention of coming to an advantageous agreement with the British Government in London on the amount of taxes due, and at the same time consolidating his right of ownership, Spotswood left for England in 1724. His stay in England lasted longer than expected on account of some complications, which included quantifying the extension of the land in his possession and the amount of tax to be paid. It lasted in all five years.[109]

Up till now, at age forty-eight, Spotswood had remained a bachelor waiting for the opportunity to marry a woman of high social standing. Now, on this occasion and in the capital, shortly after his arrival, Spotswood married Anne Butler Brayne, the daughter of a London esquire and godchild of James Butler, 2nd Duke of Ormond. They had four children, two boys and two girls.[110]

The last years

[edit]Having obtained favourable tax conditions, in February 1729 Spotswood crossed the Atlantic for the fourth and final time, with his wife and children. During his absence, the volume of production in the metallurgical plant had dropped and some slaves had escaped, but this had not affected the activities in the estate as a whole.[111] On the contrary, the prolonged active state of the furnaces made this the first stable site of this type in all of North America.[112]

As a private citizen, Spotswood financed the construction of a church in Germanna and began building another private residence in his own forest along the Rappahannock River. The construction ended in 1732. The structure, which was destroyed in the 1750s, had a park and a cherry tree boulevard, and was larger than the Williamsburg Governor's Palace. During this period, Spotswood made peace with William Byrd. After the completion of the building Byrd wrote a detailed description of the residence, which he called an "enchanted castle",[113] and of the solitary and measured lifestyle of its owner.[114][115]

During this time, Spotswood acquired another property near Yorktown, called Temple Farm. A few decades later the house, known as Moore House from the surname of Spotswood's son-in-law who inherited it, was the theatre of a crucial episode of the American Revolution, when in 1781 General Charles Cornwallis signed the final British surrender.[116]

During the last few years of his life, Spotswood stayed away from the frenzy of political life. At the time of Byrd's visit, some ministers in London were thinking of offering him (as Byrd testifies)[117] the post of governor of the colony of Jamaica, with the task of taking Spanish Havana with a military action. However, nothing came of it, as it was eventually decided to resort to more peaceful ways of dealing with the Spaniards. Spotswood accepted instead a less up-front mandate, which allowed him to return to projects developed during his years as governor: in 1730 he was appointed with a ten-year term Postmaster General for the thirteen colonies and the West Indies.[118]

At the time, the postal system covered only the coastal strip extending from New England to Pennsylvania up to Philadelphia. Virginia, cut off from courier routes, received mail once every two weeks.[119] In 1732, Spotswood extended the postal system to Williamsburg, where the mail started to arrive on a weekly basis.[120] Spotswood also entered into a partnership with the young publisher Benjamin Franklin, with whom he developed a personal friendship, appointing him, in 1737, postmaster for his city, Philadelphia.[121][122]

War of Jenkins' Ear and death

[edit]In October 1739, due to the constant attacks on the English merchant navy by Spanish naval ships, Britain declared war on Spain. The conflict would go down in history as the war of Jenkins' Ear, named after an English captain whose ear was cut off by the Spaniards. Spotswood, who had not lost interest in military affairs, proposed to the general command of London that he personally recruit a regiment of volunteers to be employed in South America. Having obtained approval, he was appointed major general and quartermaster of the troops stationed in America, crowning thus with a promotion his military career. He was to be the leader and the organiser of a military expedition against the Spanish stronghold of Cartagena de Indias, in present-day Colombia.[123]

At the beginning of the following May, Spotswood travelled to Annapolis, Maryland, to consult with the local governors, wait there for the arrival of his troops and later to set sail with them. But in Annapolis he was taken ill, and his death came quickly, on June 7, 1740, at the age of sixty-four. The expedition to Cartagena was postponed for a year, when the British forces placed the city under siege, but were utterly defeated.[4][124]

Spotswood's body was probably buried in Annapolis, but it is possible that it was brought back home to his Temple Farm property near Yorktown and buried near the York River.[124][125][126] In any case, the memory of Spotswood, and in particular of his government, lasted in Williamsburg for a long time to come.[127]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Havighurst, p. 4

- ^ Campbell, 1868, p. 12

- ^ Campbell, 1868, pp. 3–12; Havighurst, p. 5

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Shrock

- ^ Havighurst, p. 1; Howison, p. 413

- ^ a b Germanna Research Group

- ^ Wolfe, Brendan (11 August 2017). "Colonial Virginia". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ Havighurst, p. 2

- ^ Havighurst, p. 11

- ^ ^ Brock, p. ix; Fiske, p. 371

- ^ Campbell, 1860, p. 391; Havighurst, pp. 3, 21

- ^ a b Havighurst, p. 16

- ^ Havighurst, pp. 12–13

- ^ Ford, pp. 5-6; Havighurst, p. 18

- ^ Campbell, 1860, p. 404; Havighurst, p. 15

- ^ Campbell, 1860, p. 379; Havighurst, pp. 25–26

- ^ Havighurst, p. 26

- ^ Havighurst, p. 27; Shefveland, p. 93

- ^ Havighurst, pp. 28–29

- ^ Havighurst, pp. 30–31

- ^ Havighurst, pp. 32–33

- ^ Havighurst, p. 34

- ^ Havighurst, pp. 36–37

- ^ Havighurst, pp. 40–41

- ^ Havighurst, p. 42; Howison, p. 415

- ^ a b Havighurst, p. 48

- ^ a b Campbell, 1860, p. 381

- ^ Ford, pp. 29–30; Havighurst, p. 50

- ^ a b Long, Thomas L., and Quit, Martin H. (12 February 2021). "William Byrd (1674–1744)". Retrieved 11 April 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Havighurst, p. 54

- ^ Campbell, 1860, p. 392

- ^ Campbell, 1860, pp. 393–394; Havighurst, p. 55

- ^ Campbell, 1860, p. 395

- ^ a b Campbell, 1860, p. 396

- ^ Havighurst, p. 59

- ^ Howison, p. 416

- ^ Havighurst, p. 44; Shefveland, p. 95

- ^ Havighurst, pp. 22, 45; Shefveland, p. 94

- ^ a b Havighurst, p. 46

- ^ Fiske, p. 387–388; Havighurst, pp. 22–23

- ^ Fiske, p. 384

- ^ Campbell, 1860, p. 384

- ^ Havighurst, p. 27

- ^ Havighurst, p. 47

- ^ Havighurst, pp. 49–50

- ^ Havighurst, p. 68

- ^ a b Havighurst, p. 69

- ^ Havighurst, p. 70

- ^ According to some sources, the lowest peak was not called Mount Alexander, but Mount Spotswood. Campbell, 1860, p. 388

- ^ Fiske, p. 383

- ^ The name Euphrates has disappeared from maps in favour of the original Native American one. Fiske, p. 385

- ^ Campbell, 1860, p. 389

- ^ Fiske, p. 386; Havighurst, p. 71

- ^ Carpenter, Delma (October 1965). "The Route Followed by Governor Spotswood in 1716 across the Blue Ridge Mountains". Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 73, n.4. Virginia Historical Society: 405–412.

- ^ Some sources report jurat instead of juvat, which changes the meaning to "Thus, [he] swears to cross the mountains", but this lesson appears corrupted

- ^ Campbell, 1860, p. 389–390; Havighurst, p. 72; Howison, p. 418

- ^ Seagood's English translation can be found in: The William and Mary Quarterly. Vol. 7. Williamsburg. 1894. pp. 30–37.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Caruthers' text can be found here: The Knights of the Golden Horse-Shoe. 1882.

- ^ Havighurst, p. 72

- ^ Marshall, Ian (1998). Story Line: Exploring the Literature of the Appalachian Trail. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. pp. 104–106. ISBN 9780813917979.

- ^ Howison, p. 418

- ^ Havighurst, p. 75

- ^ Havighurst, p. 76

- ^ Havighurst, p. 42

- ^ Havighurst, p. 77

- ^ Havighurst, p. 8

- ^ Campbell, 1860, p. 398. For a thorough dissertation on the dispute, see Ford's monography The controversy between Lieutenant-Governor Spotswood [...], 1891, which contains the relative acts of the House of Burgesses

- ^ Havighurst, p. 78

- ^ a b Havighurst, p. 74

- ^ Havighurst, p. 73

- ^ Shefveland, pp. 99–100

- ^ Fiske, p. 366–367

- ^ Lee, pp. 95, 99

- ^ Lee, p. 105

- ^ Lee, p. 127

- ^ Havighurst, p. 81; Lee, pp. 123

- ^ Campbell, 1860, p. 397; Lee, p. 124

- ^ Lee, pp. 130–131

- ^ Havighurst, p. 83

- ^ Campbell, 1860, p. 400

- ^ Havighurst, p. 85

- ^ Havighurst, p. 86

- ^ Havighurst, p. 87

- ^ Havighurst, p. 88

- ^ Havighurst, pp. 89–90

- ^ Havighurst, pp. 91–92

- ^ a b Havighurst, p. 107

- ^ Havighurst, p. 92

- ^ Havighurst, p. 105

- ^ Havighurst, p. 90

- ^ Havighurst, p. 91

- ^ Letter dated 1 February 1720 to the London Board of Trade, in The Official Letters of Alexander Spotswood, pp. 328–335.

- ^ Havighurst, p. 97

- ^ Havighurst, p. 98

- ^ a b Havighurst, p. 99

- ^ Shefveland, p. 108

- ^ Havighurst, p. 100

- ^ The full text of the treaty can be found in: O'Callaghan, Edmund Bailey. Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York. Vol. 5. Albany: Weed, Parsons, and Co. pp. 657–681.

- ^ Campbell, 1860, p. 408; Havighurst, pp. 101–102

- ^ a b Havighurst, p. 103

- ^ Fiske, p. 389; Howison, p. 422

- ^ Havighurst, p. 104; Howison, p. 414

- ^ Ford, pp. 27–28

- ^ Campbell, 1860, pp. 403–404; Fiske, p. 389

- ^ Jones, Hugh (1724). The Present State of Virginia (PDF). London.

[T]he Country may be said to be altered and improved in Wealth and polite Living within these few Years, since the Beginning of Colonel Spotswood's Government, more than in all the Scores of Years before that, from its first Discovery.

- ^ Havighurst, p. vii

- ^ Fiske, pp. 303, 370–372

- ^ Hershberger Miller, Cathy. "Alexander Spotswood". e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Havighurst, p. 109

- ^ Campbell, 1868, pp. 15, 19–20

- ^ Havighurst, p. 108

- ^ Campbell, 1860, p. 405

- ^ Byrd, p. 132

- ^ Byrd, William (1841). "A Progress to the Mines". The Westover Manuscripts. Petersburg: Edmund Ruffin. pp. 123–143.

- ^ Havighurst, pp. 109–110

- ^ Campbell, 1868, p. 17

- ^ Byrd, p. 137

- ^ Campbell, 1860, p. 404; Havighurst, p. 111

- ^ Smith, p. 268

- ^ Campbell, 1860, p. 422; Smith, p. 269

- ^ Smith, p. 270

- ^ Lemay, Leo (2006). The life of Benjamin Franklin. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 384. ISBN 9780812238556.

- ^ Havighurst, p. 113

- ^ a b Havighurst, p. 114

- ^ Campbell, 1860, p. 407; Campbell, 1868, p. 18

- ^ The hypothesis of a burial in Yorktown, although not supported by the presence of a tombstone, seems to be reflected in some findings. See "Most of Virginia History" (PDF). Richmond Times-Dispatch (published 1 January 1915). 17 April 2021.

- ^ Havighurst, p. 112

Bibliography

[edit]- Brock, Robert Alonzo. "Preface". The Official Letters of Alexander Spotswood. pp. vii–xvi.

- Campbell, Charles (1860). History of the Colony and Ancient Dominion of Virginia. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 663250119.

- Campbell, Charles (1868). Genealogy of the Spotswood Family in Scotland and Virginia. Albany: Joel Munsell. OCLC 367860919.

- Fiske, John (1897). Old Virginia and Her Neighbours. Vol. 2. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 370–390.

- Fontaine, William Winston (1881). The Descent Of General Robert Edward Lee From Robert The Bruce, Of Scotland. Louisville: Southern Historical Society. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- Ford, Worthington Chauncey (1891). The controversy between Lieutenant-Governor Spotswood [...]. Brooklyn: Historical Printing Club.

- Havighurst, Walter (1967). Alexander Spotswood: Portrait of a Governor. Williamsburg: Holt McDougal. OCLC 574526670.

- Howison, Robert Reid (1846). A History of Virginia. Philadelphia: Carey & Hart. OCLC 609214258.

- Lee, Robert Earl (1974). Blackbeard the Pirate. Winston-Salem: John F. Blair. ISBN 0-89587-032-0.

- Shefveland, Kristalyn Marie (2016). Anglo-Native Virginia: Trade, Conversion, and Indian Slavery in the Old Dominion, 1646–1722. Athens: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-82035-025-7.

- Smith, William (1916). "The Colonial Post-Office" (PDF). The American Historical Review. 21 (2). Oxford University Press: 258–275. doi:10.2307/1835049. JSTOR 1835049.

Spotswood's correspondence

[edit]- The Official Letters of Alexander Spotswood. Collections of the Virginia Historical Society. Richmond: Virginia Historical Society. 1882. OCLC 865705257., collection of Spotswood's letters as governor of Virginia from 20 June 1710 to 28 July 1721.

- Cappon, Lester J.; Spotswood, Alexander; Spotswood, John (1952). "Correspondence of Alexander Spotswood with John Spotswood of Edinburgh". The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 2. 60 (2). Richmond: Virginia Historical Society: 211–240. JSTOR 4245835. OCLC 950897697., correspondence between Alexander Spotswood and his cousin John Spotswood.

External links

[edit]- Germanna Research Group. "Alexander Spotswood". Archived from the original on 4 October 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- Morgan, Gwenda (2008) [2004]. "Spotswood, Alexander". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/26164. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Shrock, Randall (12 February 2021). "Alexander Spotswood (1676–1740)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities.

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- Doyle, John Andrew (1898). "Spottiswood, Alexander". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 53.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Spotswood, Alexander". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- People from Tangier

- Royal Lincolnshire Regiment officers

- Foundrymen

- Colonial governors of Virginia

- 1676 births

- 1740 deaths

- British emigrants to the Thirteen Colonies

- People from English Tangier

- Spottiswoode family

- British Army major generals

- British Army personnel of the War of the Spanish Succession

- British Army personnel of the War of Jenkins' Ear

- People involved in anti-piracy efforts

- British slave owners