Battle of New Orleans

| Battle of New Orleans | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of 1812 | |||||||

The battle as painted by Jean Hyacinthe de Laclotte, a member of the Louisiana Militia, based on his sketches made at the scene | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| c. 5,700[3] | c. 8,000[3][a] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

Location in Louisiana | |||||||

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815, between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson,[3] roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the French Quarter of New Orleans,[7] in the current suburb of Chalmette, Louisiana.[1][3]

The battle was the climax of the five-month Gulf Campaign (September 1814 to February 1815) by Britain to try to take New Orleans, West Florida, and possibly Louisiana Territory which began at the First Battle of Fort Bowyer. Britain started the New Orleans campaign on December 14, 1814, at the Battle of Lake Borgne and numerous skirmishes and artillery duels happened in the weeks leading up to the final battle.

The battle took place 15 days after the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, which formally ended the War of 1812, on December 24, 1814, though it would not be ratified by the United States (and therefore did not take effect) until February 16, 1815, as news of the agreement had not yet reached the United States from Europe.[8] Despite a British advantage in numbers, training, and experience, the American forces defeated a poorly executed assault in slightly more than 30 minutes. The Americans suffered 71 casualties, while the British suffered over 2,000, including the deaths of the commanding general, Major General Sir Edward Pakenham, and his second-in-command, Major General Samuel Gibbs.

Background

[edit]In August 1814, Britain and the United States began negotiations to end the War of 1812.[9] However, British Secretary of State for War and the Colonies Henry Bathurst issued Pakenham's secret orders on October 24, 1814, commanding him to continue the war even if he heard rumors of peace. Bathurst expressed concern that the United States might not ratify a treaty and did not want Pakenham either to endanger his forces or miss an opportunity for victory.[10][b] Prior to that, in August 1814, Vice Admiral Cochrane had convinced the Admiralty that a campaign against New Orleans would weaken American resolve against Canada and hasten a successful end to the war.[c]

There was a major concern that the British and their Spanish allies wanted to reclaim the territories of the Louisiana Purchase because they did not recognize any land deals made by Napoleon (starting with the 1800 Spanish cession of Louisiana to France, followed by the 1804 French sale of Louisiana to the United States). This is why the British invaded New Orleans in the middle of the Treaty of Ghent negotiations. It has been theorized that if the British had won the Battle of New Orleans, they would have likely interpreted that all territories gained from the 1803 Louisiana Purchase would be void and not part of U.S. territory.[13] There was great concern by the Americans that Britain would hold onto the territory indefinitely, but it is left unanswerable due to the outcome of the New Orleans battle. This is contradicted by the content of Bathurst's correspondence,[10][14] and disputed by Latimer,[15][16] [17] with specific reference to correspondence from the Prime Minister to the Foreign Secretary dated December 23, 1814.[18]

Opposing forces

[edit]Prelude

[edit]Lake Borgne

[edit]

A fleet of British ships had anchored in the Gulf of Mexico to the east of Lake Pontchartrain and Lake Borgne by December 14, 1814, under the command of Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane.[19][20] An American flotilla of five gunboats, commanded by Lieutenant Thomas ap Catesby Jones, blocked British access to the lakes. On December 14, around 980 British sailors and Royal Marines under Captain Nicholas Lockyer[19] set out to attack Jones's force. Lockyer's men sailed in 42 rowboats, almost all armed with a small carronade. Lockyer captured Jones's vessels in a brief engagement. Casualties included 17 British sailors killed and 77 wounded, while 6 Americans were killed, 35 wounded, and the remaining crews captured.[21][22] The wounded included both Jones and Lockyer.

One unintended consequence is that it is believed the gunboat crews in captivity were able to mislead the British as to Jackson's strength in numbers, when they were questioned.[23][24][25] There is a popular story concerning Purser Thomas Shields and Surgeon Robert Morrell, who were sent under a flag of truce to negotiate the return of the prisoners on parole. They were placed in a cabin where their conversation could be heard. Shields, having hearing difficulties, talked loudly and mentioned that 20,000 troops were under Jackson's command. There was nothing in the actions of the British commanders to indicate they believed they were faced with superior numbers.[26]

Disembarkation by the British

[edit]Sixteen hundred British soldiers under the command of General John Keane were rowed 60 miles west from Cat Island to Pea Island (possibly now Pearl Island), situated about 30 miles (48 km) east of New Orleans. It took six days and nights to ferry the troops, each transit taking around ten hours.[27]

There were three potential routes to the east of the Mississippi that the British could take, in addition to traversing up the Mississippi itself. [24] Rather than a slow approach to New Orleans up the Mississippi River, the British chose to advance on an overland route.[28] The first route was to take the Rigolets passage into Lake Pontchartrain, and thence to disembark two miles north of the city. One hindrance was the fort at Petit Coquilles at the Rigolets passage.

The second option was to row to the Plain of Gentilly via the Bayou Chef Menteur, and to take the Chef Menteur Road that went from the Rigolets to the city. It was narrow, and could be easily blocked. Jackson was aware of this, and had it well guarded.[24]

The third option was to head to Bayou Bienvenue, then Bayou Mazant and via the Villeré Canal to disembark at a point one mile from the Mississippi and seven miles south of the city. This latter option was taken by Keane.[24]

Andrew Lambert notes that Keane squandered a passing opportunity to succeed, when he decided to not take the open road from the Rigolets to New Orleans by way of Bayou Chef Menteur.[28] Reilly observes that there has been a general acceptance that Cochrane cajoled Keane into a premature and ill-advised attack, but there is no evidence to support this theory.[29] Codrington's correspondence does imply that the first option was intended to be followed by Cochrane, based upon inaccurate map details, as documented by Cochrane's papers. The shallow waters of the narrow passes of the Rigolets and the Chef Menteur could not take any vessel drawing eight feet or more.[30]

A further hindrance was the lack of shallow draft vessels, which Cochrane had requested, yet the Admiralty had refused.[31] As a consequence, even when using all shallow boats, it was not possible to transport more than 2,000 men at a time.[32][24][30]

Villeré Plantation

[edit]

On the morning of December 23, Keane and a vanguard of 1,800 British soldiers reached the east bank of the Mississippi River, 9 miles (14 km) south of New Orleans.[34] They could have attacked the city by advancing a few hours up the undefended river road, but Keane decided to encamp at Lacoste's Plantation[35] and wait for the arrival of reinforcements.[36] The British invaded the home of Major Gabriel Villeré, but he escaped through a window[36][37] and hastened to warn General Jackson of the approaching army and the position of their encampment.[38]

Commencement of battle

[edit]Jackson's raid on the British camp

[edit]Following Villeré's intelligence report, on the evening of December 23, Jackson led 2,131[40] men in a brief three-pronged assault from the north on the unsuspecting British troops, who were resting in their camp. He then pulled his forces back to the Rodriguez Canal, about 4 miles (6.4 km) south of the city. The Americans suffered 24 killed, 115 wounded, and 74 missing,[41] while the British reported their losses as 46 killed, 167 wounded, and 64 missing.[42][d] The action was consequential, since at December 25 Pakenham's forces now had an effective strength of 5,933 out of a headcount of 6,660 soldiers.[44] Historian Robert Quimby states that the British won a "tactical victory, which enabled them to maintain their position",[45] but they "were disabused of their expectation of an easy conquest".[46] As a consequence, the Americans gained time to transform the canal into a heavily fortified earthwork.[47]

British reconnaissance-in-force

[edit]On Christmas Day, General Edward Pakenham arrived on the battlefield. Two days later he received nine large naval artillery guns from Admiral Cochrane along with a hot shot furnace to silence the two U.S. Navy warships, the sloop-of-war USS Louisiana and the schooner USS Carolina, that were harassing the army for 24 hours per day the past week from the Mississippi River. The Carolina was sunk in a massive explosion by the British, but the Louisiana survived thanks to the Baratarian pirates aboard getting into rowboats and tying the ship to the rowboats and rowing it further north away from the British artillery. The Louisiana was not able to sail northward under her own power due to the attack. These two vessels were now no longer a danger to the British, but Jackson ordered the ships' surviving guns and crew to be stationed on the west bank and provide covering fire for any British assault on the river road to Line Jackson (name of the U.S. defensive line at the Rodriguez Canal) and New Orleans. After silencing the two ships, Pakenham ordered a reconnaissance-in-force on December 28 against the earthworks. The reconnaissance-in-force was designed to test Line Jackson and see how well-defended it was, and if any section of the line was weak the British would take advantage of the situation, break through, and call for thousands of more soldiers to smash through the defenses. On the right side of this offensive the British soldiers successfully sent the militia defenders into a retreating panic with their huge show of force and were just a few hundred yards from breaching the defensive line, but the left side of the reconnaissance-in-force turned into disaster for the British. The surviving artillery guns from the two neutralized warships successfully defended the section of Line Jackson closest to the Mississippi River with enfilading fire, making it look like the British offensive completely failed even though on the section closest to the swamp the British were on the verge of breaking through. Pakenham inexplicably decided to withdraw all the soldiers after seeing the left side of his reconnaissance-in-force collapsing and retreating in panic. The British suffered 16 killed and 43 wounded and the Americans suffered 7 killed and 10 wounded. Luck saved Line Jackson on this day and this was the closest the British came during the whole campaign to defeating Jackson.[48]

After the failure of this operation Pakenham met with General Keane and Admiral Cochrane that evening for an update on the situation. Pakenham wanted to use Chef Menteur Pass as the invasion route, but he was overruled by Admiral Cochrane, who insisted that his boats were providing everything needed.[49] Admiral Cochrane believed that the veteran British soldiers would easily destroy Jackson's ramshackle army, and he allegedly said that if the army did not do it, his sailors would, and the meeting settled the method and place of the attack.[50]

When the British reconnaissance force withdrew, the Americans immediately began constructing earthworks to protect the artillery batteries, further strengthening Line Jackson. They installed eight batteries, which included one 32-pound gun, three 24-pounders, one 18-pounder, three 12-pounders, three 6-pounders, and a 6-inch (150 mm) howitzer. Jackson also sent a detachment to the west bank of the Mississippi to man two 24-pounders and two 12-pounders on the grounded warship USS Louisiana. Jackson in the first week of the New Orleans land campaign that began on December 23 also had the support of the warships in the Mississippi River, including USS Louisiana, USS Carolina, the schooner USS Eagle, and the steamboat Enterprise. The naval warships were neutralized by the heavy naval artillery guns brought in by Pakenham and Cochrane a few days after Christmas. Major Thomas Hinds' Squadron of Light Dragoons, a militia unit from the Mississippi Territory, arrived at the battle on December 22.[51]

Artillery duel

[edit]

The main British army arrived on New Year's Day 1815 and began an artillery bombardment of the American earthworks. Jackson's headquarters, Macarty House, was fired at for the first 10 minutes of the skirmish while Jackson and his officers were eating breakfast. The house was completely destroyed but Jackson and the officers escaped harm. The Americans recovered quickly and mobilized their own artillery to fire back at the British artillery. This began an exchange of artillery fire that continued for three hours. Several of the American guns were silenced, including the 32-pounder, a 24-pounder, and a 12-pounder, while some damage was done to the earthworks. The British suffered even greater, losing 13 guns (five British batteries out of seven total batteries were silenced by the Americans). The remaining British artillery finally exhausted its ammunition, and Pakenham canceled the attack. Major General Gibbs during the artillery duel sent soldiers to try to outflank Line Jackson on the right due to the near-success of the December 28 skirmish. A combined force of Tennessee militia and Choctaw warriors used heavy small arms fire to repel this maneuver. The Tennessee and Choctaw soldiers even moved forward in front of Line Jackson and counterattacked, guerrilla-style, to guarantee the British withdrawal. After yet another failure to breach Line Jackson Pakenham decided to wait for his entire force of 8,000 men to assemble before continuing his attack (the 40th Foot arrived too late, disembarking on 12 January 1815.[52]). The British lost 45 killed and 55 wounded in the artillery duel and the Americans lost 11 killed and 23 wounded.

Battle

[edit]

The Americans had constructed three lines of defense, with the forward line four miles south of the city. It was strongly entrenched at the Rodriguez Canal, which stretched from a swamp to the river, with a timber, loop-holed breastwork and earthworks for artillery.[53][54] General Lambert and two infantry battalions totaling 1700 soldiers disembarked and reinforced the British on January 5.[55] This brought the amount of disembarked men to about 8,000.[e]

The British battle plan was for an attack against the 20-gun right bank battery, then to turn those guns on the American line to assist the frontal attack.[57] Colonel William Thornton was to cross the Mississippi during the night with his force, move rapidly upriver, storm the battery commanded by Commodore Daniel Patterson on the flank of the main American entrenchments, and then open an enfilading fire on Jackson's line with the captured artillery, directly across from the earthworks manned by the vast majority of the American troops.

On the other bank, Major General Samuel Gibbs was to lead the main assault against the center left by his brigade. As a feint, a column of light infantry companies (from 4th, 21st Foot) led by Lieutenant Colonel Robert Rennie would march along the river. This would be 'considered as belonging to' the Brigade commanded by General Keane. Keane's men would move to either exploit the success along the river, or move against the center in support of Gibbs. The right flank, along the swamp, was to be protected by light infantry (detached from 7th, 43rd, 93rd Foot) commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Timothy Jones (of the 4th Foot). The brigade commanded by Major General John Lambert was held in reserve.[f]

The start of the battle was marked by the launch of a signal rocket[59] at 6:20am, soon after followed by artillery fire from the British lines towards Jackson's headquarters at the McCarty house.[60]

Right Bank

[edit]The preparations of the British had not gone unnoticed.[61] The British dug a canal to enable 42 small boats to get to the river.[57] Preparations for the attack had floundered early on January 8, as the canal collapsed and the dam failed, leaving the sailors to drag the boats through the mud with Thornton's right bank assault force. This left the force starting off just before daybreak, eight hours late according to Thornton's dispatch,[g] assessed in 2008 to be 12 hours late.[62][h] In the early morning of January 8, Pakenham gave his final orders for the two-pronged assault. The frontal attack was not postponed, however, as the British hoped that the force on the right bank would create a diversion, even if they did not succeed in the assault.[57]

As a consequence of the sides of the canal caving in and choking the passage that night, only enough boats got through to carry 560 men,[64][65][g] [i][j] just one-third of the intended force.[k] Captain Rowland Money led the Navy detachment, and Brevet Major Thomas Adair led the Marines. Money was captain of HMS Trave, and Adair was the commanding officer of HMS Vengeur's detachment of Marines.[70] Thornton did not make allowance for the current, and it carried him about two miles below the intended landing place.

The only British success of the battle was the delayed attack on the right bank of the Mississippi River, where Thornton's brigade of the 85th Regiment of Foot and detachments from the Royal Navy and Royal Marines[71] attacked and overwhelmed the American line.[42] The 700 militiamen were routed.[72] The British had the advantage of the element of surprise. The decision by General Morgan to deploy his troops in two positions a mile apart, neither defensible, was favorable for the British. Morgan's mismanagement of his Kentucky and Louisiana militiamen was an open invitation to defeat.[73] Whilst the retreat of the militia has been criticized, such a move was no less than prudent.[74] An inquiry found that the conduct was 'not reprehensible'.[75] Major Paul Arnaud, commanding officer of the 2nd Louisiana militia brigade, was targeted as a scapegoat for the retreat on the Right Bank.[76] His fellow Louisiana Militia officers Dejean, Cavallier and Declouet were admonished, as was Davis of the Kentucky Militia.[77]

At around 10 am, Lambert was made aware that the right bank had been taken,[78][79] as signalled by a rocket launched by Gubbins. His brigade won their battle, but Thornton was badly wounded, and delegated his command to Gubbins. Army casualties among the 85th Foot were two dead, one captured, and 41 wounded,[42] the battalion reduced to 270 effectives on the Right Bank.[80] Royal Navy casualties were two dead, Captain Rowland Money and 18 seamen wounded. Royal Marine casualties were two dead, with three officers, one sergeant, and 12 other ranks wounded. By contrast, the defenders' casualties were two dead, eleven wounded and nineteen missing.[81][82][83] Both Jackson and Commodore Patterson reported that the retreating forces had spiked their cannon, leaving no guns to turn on the Americans' main defense line; Major Michell's diary, however, claims that he had "commenced cleaning enemy's guns to form a battery to enfilade their lines on the left bank".[84]

General Lambert ordered his Chief of Artillery Colonel Alexander Dickson to assess the position. Dickson reported back that no fewer than 2,000 men would be required to hold the position. Lambert issued orders to withdraw after the defeat of their main army on the east bank and retreated, taking a few American prisoners and cannon with them.[42][85] The Americans were so dismayed by the loss of this battery, which would be capable of inflicting much damage on their lines when the attack was renewed, that they were preparing to abandon the town when they received the news that the British were withdrawing, according to one British regimental historian.[86] Reilly does not agree, but does note that Jackson was eager to send Humbert to take command of 400 men to retake the position from Thornton's troops.[84][l] Carson Ritchie goes as far to assert that 'it was not Pakenham, but Sir Alexander Dickson who lost the third battle of New Orleans' in consequence of his recommendation to evacuate the Right Bank,[84] and that 'he could think of nothing but defense'.[84]

This success, being described as 'a brilliant exploit by the British, and a disgraceful exhibition [of General Morgan's leadership] by the Americans,'[90][91] had no effect on the outcome of the battle.[90][91]

Left Bank

[edit]

Preparation for the assault by the 44th Foot

[edit]The 44th Regiment of Foot was assigned by General Edward Pakenham to be the advance guard for the first column of attack on 8 January 1815, and to carry the fascines and ladders which would enable the British troops to cross the ditch and scale the American ramparts. The commanding officer of the 44th, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Mullins had been commended twice during the Chesapeake campaign, and was recently promoted. He was noted as being haughty, and less than diligent in his duties as a staff officer in the days prior to the attack.[92] Pakenham ordered Mullins to determine the locations of those fascines and ladders that evening of the 7th, in order that there would be no delays in retrieving them the following morning.[92]

Gibbs also instructed him to confirm the locations of those fascines and ladders. Mullins delegated this to a subordinate, Johnston, who went to headquarters to do so. Whilst there, he was observed by General Gibbs, who enquired what he was doing. Upon being told, Gibbs wrote a formal order to Mullins that 'The Commanding Officer of the 44th will ascertain where the fascines and Ladders are deposited this evening.' A map of where the items were stored was given to Johnston. Upon returning, he presented the map to Mullins, which he dismissively put in his waistcoat.[93]

At 5 pm that evening, Mullins summoned his officers for a meeting, to discuss the attack. One of his subordinates questioned the location of the ladders, and received a caustic rebuke. He was approached by his Captain and hut-mate at 8 pm, and diplomatically suggested preparing for the next day, including the order from Gibbs to personally see where the items were stored. Mullins was dismissive, and stated there would be plenty of time in the morning.[93] Pakenham sent an order to an engineer officer to communicate with Mullins as to where the items were stored, in the redoubt. Coincidentally, Mullins arrived in the presence of the engineer officer and the artillery officer. Upon being read Pakenham's instructions, and being asked if he had any questions, Mullins replied that it was clear.[94]

During the night, an advance battery was set up forward of the advance redoubt, a distance of about 880 yards (800 m) [95] or 500 yards (460 m),[96] positioned 800 yards (730 m) south from Line Jackson.[m] Mullins, thinking this to be the location of the materiel, passed the advance redoubt and halted the regiment at the battery. Upon discovering his mistake, he sent about 300 of his 427 men back to the redoubt at the double-quick to pick up the fascines and ladders, but it was too late. The other regiments were already advancing behind the 44th, the party of 300 lost formation as they struggled to reach the redoubt, and as day dawned, the attack commenced before the supplies could be brought forward.[98][99]

The attack on the Left Bank

[edit]The main attack began in darkness and a heavy fog, but the fog lifted as the British neared the main American line, exposing them to withering artillery fire. The British column had already been disordered by the passage of the 300 returning to the redoubt, and they advanced into a storm of American fire. Without the fascines and ladders, they were unable to scale and storm the American position. [53] The British forces fell into confusion, thrown into disorder by the flight of the advance guard.[73] Most of the senior officers were killed or wounded, including Major General Samuel Gibbs, who was killed leading the main attack column on the right, and Colonel Rennie, who led a detachment on the left by the river.[100] Mullins had compromised their attack.[101]

The Highlanders of the 93rd Regiment of Foot were ordered to leave Keane's assault column advancing along the river, possibly because of Thornton's delay in crossing the river and the artillery fire that might hit them, and to move across the open field to join the main force on the right. Keane fell wounded as he crossed the field with the 93rd. Rennie's men managed to attack and overrun an American advance redoubt next to the river, but they could neither hold the position nor successfully storm the main American line behind it without reinforcements.[100] Within a few minutes, the American 7th US Infantry arrived, moved forward, and fired upon the British in the captured redoubt; within half an hour, Rennie and nearly all of his men were dead. In the main attack on the right, the British infantrymen flung themselves to the ground, huddled in the canal, or were mowed down by a combination of musket fire and grapeshot from the Americans. A handful made it to the top of the parapet on the right, but they were killed or captured. The riflemen of the 95th Regiment of Foot had advanced in open skirmish order ahead of the main assault force and were concealed in the ditch below the parapet, unable to advance further without support.

The two large main assaults were repulsed. Pakenham and Gibbs were fatally wounded while on horseback by grapeshot fired from the earthworks.[102] Major Wilkinson of the 21st Regiment of Foot reformed his lines and made a third assault. They were able to reach the entrenchments and attempted to scale them. Wilkinson made it to the top before being shot. The Americans were amazed at his bravery and carried him behind the rampart.[103][104] The British soldiers stood out in the open and were shot apart with grapeshot from Line Jackson, including the 93rd Highlanders, having no orders to advance further or retreat.[102]

The light infantry companies commanded by Jones attacked the right flank, but were repulsed by Coffee's troops. The attack having failed, the troops withdrew, and sought cover in the woods. Lieutenant Colonel Jones was mortally injured.[105][106][107]

General Lambert was in the reserve and took command. He gave the order for his reserve to advance and ordered the withdrawal of the army. The reserve was used to cover the retreat of what was left of the British army in the field. Artillery fire from both sides ceased at 9 am[108] with American batteries ceasing at 2 pm.[109] Whilst the attack was of two hours duration, the main assault lasted only thirty minutes.[110]

Analysis

[edit]The Battle of New Orleans was remarkable both for its apparent brevity and its casualties, though some numbers are in dispute and contradict the official statistics. The defenders of the Left Bank had casualties amounting to 11 killed and 23 wounded;[83] American losses were only 13 killed, 39 wounded, and 19 missing or captured in total on that day.[4] Robert Remini[6] and William C Davis[111] make reference to the British casualty reports of 291 killed, 1,262 wounded, and 484 missing, a total loss of 2,037 men. Among the prisoners taken when the British retreated from the battlefield, Jackson estimated three hundred were mortally wounded.[112] Colonel Arthur P. Hayne's dispatch to Jackson dated January 13 estimated the British had 700 fatalities and 1400 wounded, with 501 prisoners of war in his custody.[113] A reduction in headcount due to 443 British soldiers' deaths since the prior month was reported on January 25, which is lower than Hayne's estimate of 700 for the battle alone.[114]

The large number of casualties suffered by the British on the Left Bank reflects their failure to maintain the element of surprise, with plenty of advance notice being given to the defenders, owing to the delays in executing the attack on the Right Bank.[115] The failure of the British to have breached the parapet and conclusively eliminated the first line of defense was to result in high casualties as successive waves of men marching in column whilst the prepared defenders were able to direct their fire into a Kill zone, hemmed in by the riverbank and the swamp.[116] The American cannon opened fire when the British were at 500 yards, the riflemen at 300 yards, and the muskets at 100 yards.[117]

Reilly supports the assertion that it was the American artillery that won the battle. The losses among the regiments out of range of small arms fire were disproportionately high, with almost every British account emphasizing the effect of heavy gunfire. In contrast, the riflemen of the 95th Foot in skirmish order, the most difficult target for artillery, had lost only 11 killed. Dickson's eyewitness account is clear that the British were only within musket shot range for less than five minutes. The account by Latour states the battalions of Plauché, Daquin, Lacoste, along with three quarters of the 44th US Infantry did not fire at all. In order to have inflicted such a heavy toll on the British, it would not have been possible to have done this primarily with musket fire, of which the best trained men could only manage two shots per minute.[76] Unlike their British counterparts, the American forces had larger guns, and more of them. They were situated in well-protected earthworks, with a ditch and stockade. The Americans therefore had a number of advantages, but they should not minimize the skill and bravery of their gunners.[118] Stoltz is of the opinion that Jackson was victorious because an American army guarded a strategic choke point and defended it with professionally designed fieldworks and artillery.[119]

Almost universal blame was assigned to Colonel Mullins of the 44th Foot which had been detailed to carry fascines and ladders to the front to enable the British soldiers to cross the ditch and scale the parapet and fight their way to the American breastwork. Mullins was found half a mile to the rear when he was needed at the front.[n] Pakenham learned of Mullins' conduct and placed himself at the head of the 44th, endeavoring to lead them to the front with the implements needed to storm the works, when he fell wounded after being hit with grapeshot. He was hit again while being helped to mount a horse, this time mortally wounded.[86][121]

Pakenham's choice of units has come under question. Pakenham's aide, Wylly, was scornful about the 44th Foot, and thought the 21st Foot was lacking in discipline. His most experienced infantry regiments, the 7th Foot and 43rd Foot, veterans of Wellington's Peninsular War army, were kept in reserve in the plan of attack.[122]

The inability of Thornton's troops to have taken the Right Bank at night, in advance of the main assault, meant that the British were enfiladed by the American batteries. It has been observed that Keane's failure, to have taken the Chef Menteur Road, was compounded when the aggressively natured Pakenham went ahead and launched a frontal assault before the vital flank operation on the other bank of the river had been completed, at a cost of over 2,000 casualties. [28]

Poor British planning and communication, plus costly frontal assaults against an entrenched enemy, caused lopsided British casualties.[123] The Duke of Wellington was saddened by the death of this man, his brother-in-law, with whom he had been on campaign in Spain. A grieving Wellington vented his anger towards Cochrane, whom he blamed:

I cannot but regret that he was ever employed on such a service or with such a colleague. The expedition to New Orleans originated with that colleague ... The Americans were prepared with an army in a fortified position which still would have been carried, if the duties of others, that is of the Admiral [Cochrane], had been as well performed as that of he whom we now lament.[124]

Patterson notes that the plan of attack was not his own, he conceded to follow it, despite his reservations, and his death prevented him from reformulating a subsequent attack, following the initial failure.[125]

Reilly opines that the brilliance of Cochrane's plan to take possession of the Right Bank batteries was fully comprehended, after its capture. He believes it was the failure of Pakenham's staff to wake him, and to let him know the Right Bank landing was not possible, neither at daylight, nor with the numbers of soldiers originally envisaged, more than any other action or omission in the entire campaign, that was the biggest failure on the part of the British that led to proceed with the attack, with the disastrous outcome that day.[100]

Aftermath

[edit]Fort St. Philip

[edit]Fort St. Philip, manned by an American garrison, defended the river approach to New Orleans. British naval forces attacked the fort on January 9 but withdrew after ten days of bombardment with exploding bomb shells from two bomb vessels, mounting a total of four mortars.[o] [p] In a dispatch sent to the Secretary of War, dated January 19, Jackson stated: "I am strengthened not only by [the defeat of the British at New Orleans] ... but by the failure of his fleet to pass fort St. Philip."[128]

British withdrawal

[edit]Despite news of capture of the American battery on the west bank of the Mississippi River, British officers concluded that continuing the Louisiana campaign would be too costly. Three days after the battle, General Lambert held a council of war. Deciding to withdraw, the British left camp at Villeré's Plantation by January 19.[66][129] They were not pursued in any strength.[q] The Chalmette battlefield was the plantation home of Ignace Martin de Lino (1755–1815), a Spanish veteran of the American Revolutionary War.[131] The British returned to where they had landed, a distance in excess of sixty miles. The final troops re-embarked on January 27.[132]

The British fleet embarked the troops on February 4, 1815 and sailed toward Dauphin Island at Mobile Bay on February 7, 1815.[133][134] The army captured Fort Bowyer at the entrance to Mobile Bay on February 12. Preparations to attack Mobile were in progress when news arrived of the Treaty of Ghent. General Jackson also had made tentative plans to attack the British at Mobile and to continue the war into Spanish Florida. With Britain having ratified the treaty and the United States having resolved that hostilities should cease pending imminent ratification, the British left, sailing to the West Indies.[135] The British government was determined on peace with the United States, and speculation that it planned to permanently seize the Louisiana Purchase has been rejected by historians. Thus Carr concludes, "by the end of 1814 Britain had no interest in continuing the conflict for the possession of New Orleans or any other part of American territory, but rather, due to the European situation and her own domestic problems, was anxious to conclude hostilities as quickly and gracefully as possible."[16][136]

It would have been problematic for the British to continue the war in North America, due to Napoleon's escape from Elba on February 26, 1815, which ensured their forces were needed in Europe.[137] General Lambert participated in the Battle of Waterloo, as did the 4th Foot.

Distinguished service as mentioned in dispatches

[edit]In his general orders of January 21, General Jackson, in thanking the troops, paid special tributes to the Louisiana organizations, and made particular mention of Capts. Dominique and Belluche, and the Lafitte brothers, all of the Barataria privateers; of General Garrique de Flanjac, a State Senator, and brigadier of militia, who served as a volunteer; of Majors Plauche, St. Geme. Lacoste, D'Aquin, Captain Savary, Colonel De la Ronde, General Humbert, Don Juan de Araya, the Mexican Field-Marshal; Major-General Villeré and General Morgan, the Engineers Latour and Blanchard; the Attakapas dragoons, Captain Dubuclay; the cavalry from the Felicianas and the Mississippi territory. General Labattut had command of the town, of which Nicolas Girod was then the mayor.[138][139]

Among those who most distinguished themselves during this brief but memorable campaign, were, next to the Commander-in-chief, Generals Villeré, Carroll, Coffee, Ganigues, Flanjac, Colonel Delaronde, Commodore Patterson, Majors Lacoste, Planche, Hinds, Captain Saint Gerne, Lieutenants Jones, Parker, Marent, and Dominique; Colonel Savary, a man of colour nor must we omit to mention Lafitte, pirate though he was.[140][139]

Assessment

[edit]

For the campaign, American casualties totaled 333 with 55 killed, 185 wounded, and 93 missing,[141] while British casualties totaled 2,459 with 386 killed, 1,521 wounded, and 552 missing,[142][143] according to the respective official casualty returns. A reduction in headcount due to 443 British soldiers' deaths since the prior month was reported on January 25. The effective strength of the British had reduced from 5,933[44] to 4,868 soldiers of the original force, bolstered by 681 and 785 soldiers of the 7th Foot and 43rd Foot respectively.[114] More than 600 prisoners of war were released from Jackson's captivity by March 1815.[144][145]

The hundreds of dead British soldiers were likely buried at Jacques Villeré's plantation, which was the headquarters of the British Army during the New Orleans campaign. Nobody knows exactly where their final resting spot is. The only deceased British soldiers transported back to the United Kingdom were Generals Pakenham and Gibbs.[146] Lieutenant Colonel Robert Rennie was buried by the 7th US Infantry, as ordered by Jackson, and his personal effects were passed on to Major Norman Pringle, via a flag of truce, to be passed on to Rennie's widow.[147]

A discredited historical interpretation holds that British had an ambitious colonization plan for the "Crown colony of Louisiana" if they had succeeded in capturing New Orleans and Mobile. While some British generals did speculate, the British government under Lord Liverpool rejected all such ideas and planned to finalize the peace by ratifying the Treaty of Ghent as soon as possible, regardless of what happened in New Orleans.[148][16][149] Cavell notes that there is little in the correspondence to imply that Britain planned to permanent occupy or to annex New Orleans or Louisiana territory,[150] and Davis states in his book 'no one in [the British] government seems to have advocated permanent possession'.[151]

Legacy

[edit]The battle in American historiography

[edit]The battle became historically important mainly for the meaning Americans gave it, particularly with respect to Jackson. According to Matthew Warshauer, the Battle of New Orleans meant, "defeating the most formidable army ever arrayed against the young republic, saving the nation' s reputation in the War of 1812, and establishing [Jackson] as America's preeminent hero."[152] News of victory "came upon the country like a clap of thunder in the clear azure vault of the firmament, and traveled with electromagnetic velocity, throughout the confines of the land."[153] Popular pamphlets, songs, editorials, speeches, and plays glorified Jackson's new, heroic image.

The Eighth of January was a federal holiday from 1828 to 1861, and it was among the earliest national celebrations, as "previously, Americans had only celebrated events such as the Fourth of July or George Washington's birthday on a national scale".[154] The anniversary of the battle was celebrated as an American holiday for many years called "The Eighth".[155][156]

The historiography has been revisited by contemporary historians. According to Troy Bickham, the American victory at New Orleans "did not have an impact on the war's outcome", but it shaped "how the Americans received the end of the war by creating the illusion of military victory."[157] Benn notes while American popular memory focused on the victories at Baltimore, Plattsburgh, and New Orleans to present the war as a successful effort to assert American national honor, or a Second War of Independence, in which the mighty British Empire was humbled and humiliated.[158] In keeping with this sentiment, there is a popularly held view that Britain had planned to annex Louisiana in 1815.[17] The amoral depravity of the British, in contrast with the wholesome behavior of the Americans, has the "beauty and booty" story at the center of a popular history account of Jackson's victory at New Orleans.[159] According to historian Alan Taylor, the final victory at New Orleans had in that sense "enduring and massive consequences".[160] It gave the Americans "continental predominance", while it left the indigenous nations dispossessed, powerless, and vulnerable.[161]

The role played by riflemen of Jackson's army

[edit]"The Hunters of Kentucky" was a song written to commemorate Jackson's victory over the British at the Battle of New Orleans.[162] In both 1824 and 1828 Jackson used the song as his campaign song during his presidential campaigns.[163]

"Hunters of Kentucky" propagated various beliefs about the war. One of them was calling the Pennsylvania Rifle the Kentucky Rifle. Another was crediting the riflemen with the victory of the Battle of New Orleans, when it could be said it was Jackson's artillery that was actually responsible for the win. Finally, one stanza said that the British planned to ransack New Orleans, which was unlikely to happen.[164]

In keeping with the idea of the conflict as a "second war of independence" against John Bull, the narrative of the skilled rifleman in the militia had parallels with that of the Minuteman as the key factor in winning against the British.[165]

Somewhat ironically, the Kentucky militiamen were the worst equipped of Jackson's forces. Only a third were armed, lamented Jackson to Monroe.[166] On top of this, they were poorly clothed, and were weakened from the long journey. (This explains their poor performance against Thornton's troops on the Right Bank, where they were quickly routed.) Upon learning this, Jackson was purported to have quipped 'I never in my life seen a Kentuckian without a gun, a pack of cards, and a jug of whiskey.'[167]

The author Augustus Caesar Buell had a book about Jackson published posthumously. It contains his argument that the effect of the artillery, relative to riflemen, was negligible. He 'provides the most authentic solution' by claiming to quote from a primary source document from a fictitious department of the British Army. He declared there were 3,000 men wounded or killed by rifle munitions, 326 by musket or artillery.[168] The numbers provided run counter to those in primary sources with known provenance.[6] Ritchie notes the British reserve was 650 yards away from the American line, so never came within rifle range, yet suffered 182 casualties.[169]

Histories of the battle, in particular those directed towards a popular audience, have continued to emphasize the part played by the riflemen.[170] In more recent years, starting with Brown in 1969, scholarship has revealed that the militia played a smaller role, and that most British casualties were attributed to artillery fire.[171] The engineers who oversaw the erection of the ramparts, the enslaved persons of color who built them, and the trained gunners who manned the cannons have seen their contributions understated as a consequence of these popular histories that have been written since the Era of Good Feelings.[165] Popular memory's omissions of the numerous artillery batteries, professionally designed earthworks, and the negligible effect of aimed rifle fire during that battle lulled those inhabitants of the South into believing that war against the North would be much easier than it really would be.[172]

Until fairly recently, 'the supremacy of Kentucky and Tennessee rifles in deciding the battle was undisputed.'[173] Whilst this is recognised in some contemporary sources as folklore,[174][175] it is seen as an emblem of a bygone era in Kentucky. A bronze statue was dedicated in 2015 in honor of the local Soldier - Ephraim McLean Brank - who, as legend has it, was the "Kentucky rifleman" at the Battle of New Orleans. It is situated at Muhlenburg County Courthouse in Greenville, Kentucky.[176] There are still those who are happy to read accounts of forefathers from their state, and how the 'long riflemen killed all of the officers ranked Captain and above in this battle.'[177][178] Likewise, there are contemporary secondary sources that champion the riflemen as the cause of this significant victory against the British.[179]

"Beauty and Booty" controversy

[edit]After the battle, a claim was published by George Poindexter, in a letter dated January 20 to the Mississippi Republican, that Pakenham's troops had used "Beauty and Booty" as a watchword:

The watch-word and countersign of the enemy on the morning of the 8th was,

BOOTY AND BEAUTY

Comment is unnecessary on these significant allusions held out to a licentious soldiery. Had victory declared on their side, the scenes of Havre de Grace, of Hampton, of Alexandria . . . would, without doubt, have been reacted at New Orleans, with all the unfeeling and brutal inhumanity of the savage foe with whom we are contending.

This was republished in Niles' Register,[180] the National Intelligencer on February 13, and other newspapers.[181] Whilst there were criticisms from the Federalist press, as well as from Poindexter's enemies, as to how reliable this information was, it was widely accepted elsewhere. Senator Charles Jared Ingersoll made direct reference to this in his speech to Congress on February 16, reproduced in full in the National Intelligencer.[182] He continued, in an elated manner, 'with the tidings of this triumph from the south, to have peace from the east, is such a fullness of gratification as must overflow all hearts with gratitude.'[182] He saw the news of victory at New Orleans against an immoral foe, followed by news of peace, as a positive sentiment to unite the different peoples of the United States,[183] the zeitgeist of these postwar years later becoming known as the Era of Good Feelings.

This watchword claim, as originated by Poindexter, was repeated in Eaton's "Life of General Jackson", first published in 1817. A second edition of this biography was published in 1824, when Jackson made his first presidential bid. Further editions were published for the presidential elections of 1828 and 1833.[184] Editions from 1824 onwards now contained the claim that documentary evidence proved the watchword was used.[185] As a consequence it was reproduced in a travelogue in 1833.[186]

Following the publishing of a travelogue in 1833, whereby the author James Stuart referred to the watchword,[186] this hitherto unknown controversy became known in Great Britain. In response to the author, five British officers who had fought in the battle, Keane, Lambert, Thornton, Blakeney and Dickson, signed a rebuttal in August 1833. It is stated this was published in The Times by American sources,[187][188] but this is not the case.[189] [190][191] Somewhat ironically, Niles's Register, which originally printed Poindexter's claim, now printed the British rebuttal:[192]

We, the undersigned, serving in that army, and actually present, and through whom all orders to the troops were promulgated, do, in justice to the memory of that distinguished officer who commanded and led the attack, the whole tenor of whose life was marked by manliness of purpose and integrity of view, most unequivocally deny that any such promise (of plunder) was ever held out to the army, or that the watchword asserted to have been given out was ever issued. And, further, that such motives could never have actuated the man who, in the discharge of his duty to his king and country, so eminently upheld the character of a true British soldier.[193]

James Stuart's account was criticised by a veteran, Major Pringle, who wrote several letters to the Edinburgh Evening Courant. In response, Stuart published a book to refute these criticisms.[194] He quoted Major Eaton as a reliable source, and later went on to comment that as a result of Stuart, it had become accepted the watchword was a falsehood.[195] One quote from the book 'certainly the refutation of the charge as stated in Major Eaton's Book is, though tardy, complete'[196] considered the matter closed. Notwithstanding the refutation, the story had benefited both Jackson and Eaton's political careers, who had nothing left to prove.[197]

The publication of Eaton's book in Britain in 1834, and in subsequent editions, still contained the story of "booty and beauty". The British Ambassador, Sir Charles Richard Vaughan wrote to President Jackson about the matter. Vaughan wrote that Eaton 'expressed himself glad, that the report was at last contradicted' by the rebuttal, but there was no pressure on him to retract his comments from the Jackson biography.[198] There is no recounting in 1833 of Jackson's supposed encounter with the mystery Creole planter (Denis de la Ronde), as reported by S C Arthur (see below).

Arthur's 1915 publication, quoting from Parton's 1861 biography of Jackson, itself quoting extensively from Vincent Nolte's book published in 1854, has referred to a Creole planter reportedly visited a British military camp a few days prior to the battle, being welcomed in after claiming that he was supportive of a possible British takeover of the region. While dining at dinner with a group of British officers, the planter claimed he heard one officer offer the toast of "Beauty and Booty". After gathering information on Pakenham's battle plans, the planter left the camp the next day and reported the information he had gathered to Jackson; the rumor that the British were offering toasts to "Beauty and Booty" soon spread throughout New Orleans, in particular among the upper-class women of the city.[187] Nolte's book reveals the 'planter' to be no other than Denis de la Ronde,[199] the colonel commanding the Third Regiment of the Louisiana Militia.[200]

In the years since the Treaty of Ghent, not only did Jackson's reputation benefit from his major victory against the British, but also from vilifying the British as an amoral foe, against whom a second war of independence had been fought. As a national hero, it facilitated his subsequent career in politics, and tenure as President of the United States.

Political outcomes

[edit]New England as a whole was against the war. The leaders of the Federalist Party of New England met at the Hartford Convention and decided to deliver a set of demands to the federal government in January 1815.[201] The moderates were in charge and there was no proposal to secede from the union. When the Hartford delegation reached Washington word of the great American victory at New Orleans came and the Federalists were seen as traitors and anti-American; the Federalist Party was permanently ruined.[202]

The economic impact of the War of 1812 resulted in discord for those in the northern New England states harmed by the blockade. Their concerns were voiced through the Federalist Party. The Hartford Convention saw them discuss their grievances concerning the ongoing war and the political problems arising from the federal government's increasing power. Federalists were increasingly opposed to slavery, both on principle and because the Three-fifths Compromise gave a political advantage to their opponents, who gained increased representation because of the weight given to enslaved (and therefore disenfranchised) people. This had resulted in the dominance of Virginia in the presidency since 1800.

By the time the Federalist "ambassadors" got to Washington, the war was over and news of Andrew Jackson's stunning victory in the Battle of New Orleans had raised American morale immensely. The "ambassadors" hastened back to Massachusetts, but not before they had done fatal damage to the Federalist Party. The Federalists were thereafter associated with the disloyalty and parochialism of the Hartford Convention and destroyed as a political force. Across the nation, Republicans used the great victory at New Orleans to ridicule the Federalists as cowards, defeatists and secessionists. Pamphlets, songs, newspaper editorials, speeches and entire plays on the Battle of New Orleans drove home the point.[203]

The Era of Good Feelings resulted from the Battle of New Orleans. From 1815 to 1825 there was single-party rule in Washington and an overwhelming feeling of patriotism due to the extinction of the Federalist Party. The era saw the collapse of the Federalist Party and an end to the bitter partisan disputes between it and the dominant Democratic-Republican Party during the First Party System.

Andrew Jackson served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837.

The void left by the Federalist Party was replaced by the Whig Party (United States), which came into being in 1833, in opposition to Andrew Jackson, and his policies as President. The Whig Party fell apart in the 1850s due to divisions over the expansion of slavery. Once more, a division between southern and northern states came into being.

The victory at New Orleans effectively kept the United States unified for the next 45 years until the American Civil War.

Memorials

[edit]

The Louisiana Historical Association dedicated its Memorial Hall facility to Jackson on January 8, 1891, the 76th anniversary of the Battle of New Orleans.[204] The Federal government established a national historical park in 1907 to preserve the Chalmette Battlefield, which also includes the Chalmette National Cemetery. It features the 100-foot-tall Chalmette Monument and is part of the Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve. The monument was supposed to be at least 150 feet tall but the very soft and wet soil limited it to 100 feet.[205] A five-cent stamp in 1965 commemorated the sesquicentennial of the Battle of New Orleans and 150 years of peace with Britain. The bicentennial was celebrated in 2015 with a Forever stamp depicting United States troops firing on British soldiers along Line Jackson.

Prior to the twentieth century the British government commonly commissioned and paid for statues of fallen generals and admirals during battles to be placed inside St Paul's Cathedral in London as a memorial to their sacrifices. Major Generals Pakenham and Gibbs were both memorialized in a statue at St Paul's that was sculpted by Sir Richard Westmacott.[206]

|

In popular culture

[edit]- The Buccaneer, a 1938 American adventure film made by Cecil B. DeMille starring Fredric March, was based on Jean Lafitte and the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812.

- The Buccaneer, a 1958 pirate-war film starring Yul Brynner as Jean Lafitte and Charlton Heston as Andrew Jackson, is a fictionalization of the privateer Lafitte helping Jackson win the Battle of New Orleans.

- Johnny Horton's cover of the Jimmy Driftwood song The Battle of New Orleans, which describes the battle from the perspective of an American soldier, reached number 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1959.

See also

[edit]Notes and citations

[edit]Notes

- ^ The monthly returns for British forces in North America, archive reference WO 17/1218, prepared on the 25th day of the month, provide valuable details on unit strengths. Images of the original documents can be seen on microfilm at The Historic New Orleans Collection's research center. Transcriptions of the returns are online and can be downloaded via Bamford 2014.

- ^ Lambert, p.342. 'Nor did he [Bunbury] favour attacking New Orleans... the target looked difficult with nightmarish navigation, climate, and logistics.... Despite Bunbury's incisive critique, an attack on New Orleans was ordered.'[11]

- ^ Gene Allen Smith makes reference to a letter from the Secretary of the Admiralty to Cochrane dated August 10, 1814. A copy of this document is accessible at The Historic New Orleans Collection, via microfilm. Smith also mentions how several Royal Navy officers had suggested the idea of attacking Louisiana from 1813 onwards.[12]

- ^ Despatch from Hayne to Jackson dated January 10. 'Prisoners taken [December 24]- One major, 2 lieutenants, 1 midshipman 66 non-commissioned officers and privates' [43]

- ^ 'Fresh spirit was given to the army by the unexpected arrival of Major General Lambert, with the 7th and 43rd; two fine battalions, mustering each eight hundred effective men. By this reinforcement, together with the addition of a body of sailors and marines from the fleet, our numbers amounted now to little short of eight thousand men; a force which, in almost any other quarter of America, would have been irresistible.'[56] This figure of about 8,000 is corroborated by other sources.

- ^ The battle plan was outlined in a memorandum by Pakenham, a copy of which has been reproduced.[58]

- ^ a b "Despatch from Colonel Thornton to Sir Edward Pakenham dated January 8, 1815". Thegazette.co.uk. March 9, 1815. Retrieved December 3, 2021 – via London Gazette.

We were unable to proceed across the river until eight hours after the time appointed, and even then, with only a third of the force which you had allotted for the service.

- ^ Gleig narrates in the third person of his participation on the attack on the Right Bank. 'No boats had arrived; hour after hour elapsed before they came.... Instead of reaching the opposite bank at latest by midnight, dawn was beginning to appear before the boats quitted the canal.... It was in vain that they made good their landing and formed upon the beach, without opposition or alarm; day had already broke, and the signal-rocket was seen in the air, while they were yet four miles from the batteries, which ought hours ago to have been taken.'[63]

- ^ Concerning the strength and composition of Thornton's force. Correspondence from Cochrane to Admiralty dated January 18, contained within "No. 16991". The London Gazette. March 9, 1815., also in archives with reference ADM 1/508 folio 757, states 'the whole amounting to about six hundred men'. Gleig uses the source document a report from Thornton to Pakenham 'we were unable to proceed across the river until eight hours after the time appointed, and even then with only a third part of the force which you had allotted for the service viz 298 of the 85th, and 200 Seamen and Marines.'[66] Duncan, with recourse to Dickson's papers: '[Pakenham] sent to enquire how many men had been embarked: and, having been informed that the 85th Foot, with some Marines—amounting in all to 460 — had been put on board, and that there was room for 100 more, he ordered that additional number to be embarked, and the whole to cross without delay.'[67]

- ^ 'The force of the enemy did not exceed four hundred men.' Despatch from Major Foelcker to General Jackson dated January 8, 1815. 'The force of the enemy on this side amounted to 1,000, men.' Despatch from Patterson to United States Secretary of the Navy dated January 13, 1815. Both reproduced in a secondary source[68]

- ^ Hughes & Brodine quotes from a letter from General Lambert to the Secretary of State for War dated January 10, republished in "No. 16991". The London Gazette. March 9, 1815., which mentions the original plan was to send over a larger force of a further 100 sailors, a further 300 marines, four cannons with gunners, and the battalion of the 5th West India Regiment.[69]

- ^ Davis, quoting from correspondence from Shaumburg to Claiborne, states that Humbert arrived, demanding 400 men without written orders, and was rebuffed by Morgan.[87] The written order from Jackson has survived, however, with Humbert accompanied by Lafitte. Patterson's letter dated January 13 mentions 'a large re-enforcement of militia having been immediately despatched by general Jackson to this side.'[88] Latour, an eye witness, has the following to say: '[Humbert was ordered] to cross over with a re-enforcement of four hundred men, take the command of the troops, and repulse the enemy.. The order he had received, was only verbal, owing to the urgency of the occasion. There arose disputes concerning military precedence. Other militia officers did not think it right that a French general... should be sent to remedy the faults of others...[The implication is that the militia officers were refusing to be subordinate to Humbert, and that they considered Morgan to continue to be the Commanding Officer.] Happily, during this discussion, the enemy, as I have observed, thought it prudent to retreat, which they did that night and next morning.'[89]

- ^ 'An advanced battery in our front was thrown up during the night about 800 yards from the enemy’s line.'[97]

- ^ Major McDougall, the aide-de-camp to Pakenham testified at the court martial on Mullins. 'It is my opinion, that the whole confusion of the column proceeded from the original defective formation of the 44h; the fall of Sir edward Pakenham deprived the column of its best chance of success; and, had the column moved forward according to order, the enemy's lines would have been carried with little loss.' [120]

- ^ Roosevelt dismissively summarized the engagement in one sentence: "At the same time [as the British Army's withdrawal from New Orleans], a squadron of vessels, which had been unsuccessfully bombarding Fort Saint Philip for a week or two, and had been finally driven off when the fort got [the ammunition for] a mortar large enough to reach them with, also returned; and the whole fleet [thereafter] set sail for Mobile."[126]

- ^ 'A British squadron appeared in the river below Fort St. Philip, Two bomb-vessels, under the protection of a sloop, a brig, and a schooner, bombarded the fort without effect until January 18, when they withdrew.'[127]

- ^ Despatch from Jackson to Secretary of War dated January 19. "Last night at 12 o'clock, the enemy precipitately decamped and returned to their boats, leaving behind him, under medical attendance, eighty of his wounded including two officers, 14 pieces of his heavy artillery and a quantity of shot... Such was the situation of the ground he abandoned, and of that through which he returned, protected by canals, redoubts, entrenchments and swamps on his right, and the river on his left, that I could not, without encountering a risk which true policy did not seem to require, or to authorize, attempt to annoy him much on his retreat ... [I am of] the belief that Louisiana is now clear of its enemy."[130]

Citations

- ^ a b Remini (1999), p. 136.

- ^ Anthony Eley. "Pushmataha, Brigadier General". National Museum of the United States Army. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Battle of New Orleans Facts & Summary". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved July 8, 2018.

- ^ a b Remini (1977), p. 285, quoting Jackson's report dated January 14, 1815

- ^ James, p. 563, reproducing Adjutant General Robert Butler's casualty report to Brigadier General Parker dated January 16, 1815.

- ^ a b c d Remini (1999), p. 195.

- ^ "The Battle of New Orleans". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- ^ Mclemore, Laura, ed. (2016). The Battle of New Orleans in History and Memory. Louisiana State University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-80-716466-2.

- ^ Lorusso, Nicholas J. (June 24, 2019). The Battle of New Orleans: Joint Strategic and Operational Planning Lessons Learned (Joint Professional Military Education Phase II dissertation thesis). Norfolk, VA: Joint Forces Staff College. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ a b Grodzinski (ed) (2011), p.1

- ^ Lambert (2012), p. 342.

- ^ Smith (2008), p. 89.

- ^ "Army historian corrects myths on Battle of New Orleans' 200th anniversary". Army.mil. January 9, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ "Film reel 17, War Office Records, Outletters, North America,1814", One volume of the Out-letters of Lord Bathurst, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, North America, 1814, War of 1812 Documents from the British National Archives microfilm, The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2006, WO 6/2, archived from the original on December 18, 2021, retrieved December 20, 2021

- ^ Latimer (2007), pp. 401–402.

- ^ a b c Carr 1979, p. 273–282.

- ^ a b Eustace (2012), p. 293.

- ^ British Foreign Policy Documents, p. 495.

- ^ a b Roosevelt (1900), p. 73.

- ^ Refer to the map of Louisiana.

- ^ Roosevelt (1900), p. 77.

- ^ Hickey (1989), p. 208.

- ^ Brown (1969), p. 81.

- ^ a b c d e Daughan (2011), p. 381.

- ^ Smith (2000), p. 30.

- ^ Reilly (1976), pp. 228–229.

- ^ Brown (1969), pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b c Lambert (2012), p. 344.

- ^ Reilly (1976), p. 221.

- ^ a b Reilly (1976), p. 226.

- ^ Daughan (2011), p. 379.

- ^ Gleig (1827), p. 273.

- ^ Lossing, Benson (1868). The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. Harper & Brothers, Publishers. p. 1032.

- ^ Remini (1999), p. 62–64.

- ^ Quimby, p. 836.

- ^ a b Remini 1977, p. 262.

- ^ Bunner 1855, p. 220.

- ^ Arthur 1915, p. 97.

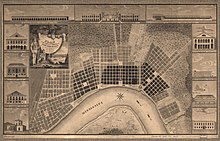

- ^ Tom (March 18, 2015). "Rare 1815 Plan of the City and Suburbs of New Orleans". Cool Old Photos. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Quimby, p. 843.

- ^ James, p. 535, reproducing Adjutant General Robert Butler's casualty report to Brigadier General Parker dated January 16, 1815.

- ^ a b c d "No. 16991". The London Gazette. March 9, 1815. pp. 440–446.

- ^ Brannan (1823), pp. 457–458.

- ^ a b Within Monthly Return, December 1814 via Bamford 2014

- ^ Quimby, p. 852.

- ^ Quimby, pp. 852–853.

- ^ Groom, pp. 145–147.

- ^ Dale 2015, pp. 97–101.

- ^ Patterson, Benton Rain, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Patterson, Benton Rain, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Remini (1999), p. 74.

- ^ Smythies, pp. 172-175

- ^ a b Porter, p. 361

- ^ Davis (2019), pp. 162–165.

- ^ Levinge 2009, p. 220: 'On the 5th of January the 7th and 43rd landed.. mustering upwards of 1700 bayonets'

- ^ Gleig (1827), p. 320.

- ^ a b c Porter, p. 362

- ^ Forrest 1961, p. 40-42.

- ^ Reilly (1976), p. 289.

- ^ Davis (2019), p. 239-241.

- ^ Hughes & Brodine 2023, p. 1011-1015.

- ^ Patterson, Benton Rain, p. 236.

- ^ Gleig (1827), p. 323.

- ^ Hickey (1989), p.211

- ^ Brown (1969), p. 152.

- ^ a b Gleig (1827), p. 340.

- ^ Duncan (1873), p. 405-406.

- ^ Hughes & Brodine (2023), p. 1014-1015,1018-1019.

- ^ Hughes & Brodine 2023, p. 1002-1006.

- ^ The Navy List, Corrected to the end of January 1815, pg 72. John Murray. 1814. p. 145. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

- ^ Patterson, Benton Rain, p. 230.

- ^ Hickey (1989), p. 211.

- ^ a b Reilly (1976), p. 298.

- ^ Reilly (1976), pp. 302–303.

- ^ Court martial of inquiry, relative to the retreat on January 8, reproduced in Latour (1816), appendix LXII, p.cxxxii

- ^ a b Reilly (1976), p. 307.

- ^ Latour 1816, p. cxxxii.

- ^ Hughes & Brodine 2023, p. 1005.

- ^ Parton 1861, p. 217.

- ^ Brown (1969), p. 156.

- ^ Greene (2009), p. 159, with reference to both Jackson's papers and Tatum's journal, both edited by Bassett

- ^ Bassett (ed) (2007), p. 130 with reference to Tatum's journal

- ^ a b Bassett (ed) (1969), p. 143 with Jackson's papers corroborating Tatum's figures

- ^ a b c d Reilly (1976), p. 305.

- ^ Patterson, Benton Rain, p. 253.

- ^ a b Porter, p. 363

- ^ Davis (2019), p. 273.

- ^ Latour 1816, p. lxii.

- ^ Latour 1816, p. 175-176.

- ^ a b Brown (1969), p. 157.

- ^ a b Roosevelt (1900), p. 232.

- ^ a b Davis (2019), p. 200.

- ^ a b Davis (2019), p. 224-225.

- ^ Davis (2019), p. 225-226.

- ^ Davis (2019), p. 226.

- ^ James (1818), p. 374-375.

- ^ Hughes & Brodine 2023, p. 1004.

- ^ Gleig (1840), p. 339.

- ^ Davis (2019), p. 232-237.

- ^ a b c Reilly (1976), p. 299.

- ^ Davis (2019), p. 238-239.

- ^ a b Reilly (1976), p. 300.

- ^ Gleig (1840), pp. 344–345.

- ^ Stuart 1834, pp. 95–98.

- ^ Reilly (1976).

- ^ Davis (2019), p. 269.

- ^ Dale 2015, pp. 160, 191.

- ^ Hughes & Brodine 2023, p. 1020.

- ^ Reilly (1976), p. 296.

- ^ Owsley 2000, p. 161.

- ^ Davis (2019), p. 278.

- ^ James, pp.557-559, contains despatch from Jackson to Secretary of War dated January 9. 'The loss which the enemy sustained on this occasion, cannot be estimated at less than 1500 in killed, wounded and prisoners. Upwards of three hundred have already been delivered over for burial.... We have taken about 500 prisoners, upwards of 300 of whom are wounded, and a great part of them mortally.'

- ^ Brannan, p.459, contains despatch from Hayne to Jackson dated January 13. 'Prisoners taken - Prisoners taken - One major, 4 captains, 11 lieutenants, 1 ensign, 483 camp followers and privates'

- ^ a b Within Monthly Return, January 1815 via Bamford 2014

- ^ Gleig (1827), p. 332.

- ^ Gleig (1827), p. 335.

- ^ Horsman (1969), p. 244.

- ^ Ritchie (1969), p. 10.

- ^ Stoltz (2017), p. 12.

- ^ Gleig (1840), p. 344.

- ^ Davis (2019), p. 255-256.

- ^ Davis (2019), p. 223.

- ^ "Alexander Cochrane". National Park Service. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ Holmes, Richard (2003). Wellington: The Iron Duke. HarperCollins. p. 206.

- ^ Patterson 2008, p. 265.

- ^ Roosevelt (1900), p. 237.

- ^ Adams (1904), p. 383.

- ^ James (1818), pp. 459–460.

- ^ Latour, p. 184

- ^ James (1818), p. 563-564.

- ^ "Chalmette Plantation". War of 1812. The historical marker database. August 23, 2016. Retrieved April 6, 2024.

Inscription: Named for Ignace Francois Martin de Lino de Chalmet (1755-1815), veteran of the American Revolution. Attained the rank of captain of infantry in the Spanish Army; retired about 1794. Purchased plantations below New Orleans and began acquisition of properties in 1805, which would become the Chalmette Plantation stretching 22 arpents along the Mississippi River; main house, sugar mill and almost all out buildings destroyed in the Battle of New Orleans. Decisive engagement on January 8, 1815. Erected by: St. Bernard Tourist Commission.

- ^ James (1818), pp. 387–388.

- ^ Gleig (1827), p. 184–192.

- ^ James (1818), p. 391.

- ^ Fraser, p. 297

- ^ Mills (1921), p. 19-32.

- ^ Lambert, p. 381 "While Napoleon remained in power, few British soldiers could be spared for North America. Wellington was always looking for more manpower."

- ^ Coleman 1885, p. 177.

- ^ a b Brannan 1823, p. 477-480.

- ^ Bunner 1855, p. 231.

- ^ James, p. 388, quoting from Butler's "report of the killed, wounded and missing" to Brigadier General Parker dated January 16, reproduced in the appendices.

- ^ An aggregation of totals for four casualty returns shows 386 killed, 1,516 wounded, and 552 missing. Casualty returns within "No. 16991". The London Gazette. March 9, 1815. pp. 443–446.

- ^ James, p. 388. states 385 killed, 1,516 wounded, and 591 missing, 39 light dragoons in a boat being added to the missing.

- ^ "POWs returned by General Andrew Jackson in 1815, a transcription". TheNapoleonicWars.net. New Work & Research. December 27, 2021. ADM 103/466. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ^ Bassett (1969), p. 157 contains a letter from Jackson to Colonel Hays dated February 4. "After the exchange is compleated [sic], there will remain between three and four hundred Prisoners in my hands".

- ^ Reilly (1976), p. 301.

- ^ Davis (2019), p. 277.

- ^ Howe 2007, p. 16.

- ^ for the discredited speculation see Abernethy, Thomas P. (1961). The South in the New Nation, 1789–1819: A History of the South. LSU Press. pp. 389–390. ISBN 9780807100042.

- ^ Cavell 2022.

- ^ Davis (2019), p. 15.

- ^ Warshauer 2013, p. 79–92.

- ^ Ward 1962, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Stoltz, Joseph F. (2012). "'It Taught our Enemies a Lesson': The Battle of New Orleans and the Republican Destruction of the Federalist Party". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 71 (2): 112–127. JSTOR 42628249.

- ^ The War of 1812 : official National Park Service handbook. Eastern National. 2013. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-57-864763-7.

- ^ Stoltz (2017), p.1 47

- ^ Bickham 2017.

- ^ Benn 2002, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Eustace 2012, p. 212.

- ^ Taylor 2010, p. 421.

- ^ Taylor 2010, p. 437.

- ^ Stoltz 2017, p. 15.

- ^ Hickey 2006, p. 347.

- ^ Hickey 2006, p. 348.

- ^ a b Stoltz 2017, p. 27.

- ^ Davis (2019), p. 197.

- ^ Buell 1904, p. 423.

- ^ Buell 1904, p. 40-42.

- ^ Ritchie 1969, p. 13.

- ^ Stoltz 2017, p. viii.

- ^ Stoltz 2017, p. 25.

- ^ Stoltz 2017, p. 47.

- ^ Ritchie 1969, p. 8.

- ^ "Americans celebrate an idealized version of their militia". April 29, 2015 – via National Park Service.

- ^ "6 Myths About the Battle of New Orleans". The History Channel, A&E Networks. MYTH #5: Kentucky riflemen were responsible for the American victory. January 8, 2015.

- ^ "The legend of Kentucky's lone marksman at the Battle of New Orleans". Kentucky National Guard. January 8, 2019.

- ^ Claypool, James (January 6, 2015). "Remarkable Kentuckians: The Sharpshooter That Broke the British in New Orleans". WKMS - Murray State's NPR Station. Murray, KY.

- ^ Cummings, Lt Col USMC Retd Edward B. (September 2023). "E Pluribus, Unum: The American Battle Line At New Orleans, 8 January 1815". The Army Historical Foundation. Fort Belvoir, VA.

Victory was made possible by an unlikely combination of oddly disparate forces, British logistic oversights and tactical caution, and superior American backwoods marksmanship.

- ^ Remini 1999, p. 146.

- ^ Poindexter, George (1815). "From the Mississippi Republican-Extra, New Orleans, January 20th, 1815". Niles's Weekly Register. Vol. 8. pp. 58–59.

BEAUTY and BOOTY. Comment is unnecessary on these significant allusions held out to a licentious soldiery.

- ^ Eustace 2012, pp. 213–215.

- ^ a b Eustace 2012, p. 215.

- ^ Eustace 2012, pp. 216, 220.

- ^ Eustace 2012, p. 229.

- ^ Eaton 1828, p. 293.

- ^ a b Stuart 1833, pp. 142–143.

- ^ a b Arthur 1915, p. 216.

- ^ Parton 1861, p. 225.

- ^ "THE TIMES DIGITAL ARCHIVE 1785-2019". The Times. Retrieved January 20, 2023 – via Gale Primary Sources.

A database search between January 1st and December 31st 1833 does not fetch the rebuttal signed by Blakeney et al

- ^ Stuart, 1834, p.105 quoting letter from Stuart to Lambert dated August 24, 1833: ' I have no other way of making the important information contained in your [rebuttal] communication generally known, than by sending it for insertion; in the public journals, and by requesting one of my friends at New York to have it inserted in newspapers published there and at Washington.'

- ^ Ingersoll, (1852), p.241 'In 1833, all the surviving British commanders... deemed it proper to publish, in an English journal [their rebuttal].' Which journal is not stated. A Scottish journal. Edinburgh Evening Courant, is the most likely.

- ^ "BEAUTY and BOOTY". Niles's Weekly Register. October 19, 1833. p. 121.

Six of the principal officers.... have distinctively denied any knowledge [of the watchword].. The following interesting documents have been sent us for insertion.

- ^ Stuart 1834, pp. 102–104.

- ^ Stuart 1834, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Stuart, 1834, pp.106–108 'Six extracts [taken in October 1833 from: New York journal of Commerce, New York Gazette and General Advertiser, Philadelphia Commercial Herald, New York Commercial Advertiser, New York American, New York Albion]..the Watchword... had been universally believed in the United States of America for eighteen years; and also shewing the good spirit with which the complete refutation of the statement had been received in America.'

- ^ Stuart 1834, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Eustace 2012, p. 230.

- ^ "Letter from Sir Charles Vaughan to Andrew Jackson, July 14, 1833". Retrieved January 20, 2023 – via Library of Congress.

- ^ Nolte 1934, p. 220.

- ^ "Denis de La Ronde Site". Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ Morison 1968, p. 38-54, 166.

- ^ Howe 2007, p. 61, 90.

- ^ Stoltz, Joseph F. (2012). ""It Taught our Enemies a Lesson:" the Battle of New Orleans and the Republican Destruction of the Federalist Party". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 71 (2): 112–127. JSTOR 42628249.

- ^ "Kenneth Trist Urquhart, "Seventy Years of the Louisiana Historical Association", March 21, 1959, Alexandria, Louisiana" (PDF). Lahistory.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2010. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- ^ "Chalmette Monument Marker". Hmdb.org. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ "Memorial to Major General The Hon Sir E Pakenham and Major General S Gibbs". IWM War Memorial Register. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

References

[edit]- Abernethy, Thomas P. (1961). The South in the New Nation, 1789–1819: A History of the South. LSU Press. ISBN 9780807100042.

- Adams, Henry (1904) [1890]. History of the United States of America during the Administration of James Madison. Vol. 8. New York: C. Scribner's sons. p. 383. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

- Arthur, Stanley Clisby (1915), The story of the Battle of New Orleans, New Orleans: Louisiana Historical Society, OCLC 493033588

- Bamford, Andrew (May 2014). "British Army Unit Strengths: 1808-1815 War of 1812 - American Coast". The Napoleon Series. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- Bassett, John Spencer, ed. (2007) [1922]. Major Howell Tatum's journal while acting topographical engineer (1814) to General Jackson, commanding the Seventh military district. Smith College studies in history. Northampton, Mass. Dept. of History of Smith College. OCLC 697990493.