Black Ships

The Black Ships (in Japanese: 黒船, romanized: kurofune, Edo period term) were the names given to both Portuguese merchant ships and American warships arriving in Japan in the 16th and 19th centuries respectively.

In 1543, Portuguese initiated the first contacts, establishing a trade route linking Goa to Nagasaki. The large carracks engaged in this trade had the hull painted black with pitch, and the term came to represent all Western vessels. In 1639, after suppressing a rebellion blamed on the influence of Christian thought, the ruling Tokugawa shogunate retreated into an isolationist policy, the Sakoku. During this "locked state", contact with Japan by Westerners was restricted to Dutch traders on Dejima island at Nagasaki.

In 1844, William II of the Netherlands urged Japan to also open the mainland to trade, but was rejected. [1] On July 8, 1853, the U.S. Navy sent four warships into the bay at Edo and threatened to attack if Japan did not begin trade with the West. The ships were Mississippi, Plymouth, Saratoga, and Susquehanna of the Expedition for the opening of Japan, under the command of Commodore Matthew Perry. The expedition arrived on July 14, 1853 at Uraga Harbor (present-day Yokosuka) in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.[2] Though their hulls were not black, their coal-fired steam engines belched black smoke.

Their arrival marked the reopening of the country to political dialogue after more than two hundred years of self-imposed isolation. Trade with Western nations followed five years later with the Treaty of Amity and Commerce. After this, the kurofune became a symbol of the end of isolation.

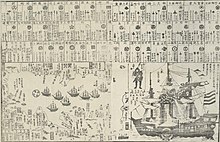

First kurofune ships: nau do trato

[edit]

In 1543 Portuguese traders arrived in Japan initiating the first contacts with the West. Soon they established a trade route linking their headquarters in Goa, via Malacca to Nagasaki. Large carracks engaged in the flourishing "Nanban trade", introducing modern inventions from the European traders, such as refined sugar, optics, and firearms; it was the firearms, arquebuses, which became a major innovation of the Sengoku period—a time of intense internal warfare—when the matchlocks were replicated. Later, they engaged in triangular trade, exchanging silver from Japan with silk from China via Macau.[3]

Carracks of 1200 to 1600 tons,[4] named nau do trato ('treaty ship') or nau da China by the Portuguese,[5] engaged in this trade had the hull painted black with pitch, and the term[6] came to apply for all western vessels. The name was inscribed in the Nippo Jisho, the first western Japanese dictionary compiled in 1603.

In 1549 Spanish missionary Francis Xavier started a Jesuit mission in Japan. Christianity spread, mingled with the new trade, making 300,000 converts among peasants and some daimyō (warlords). In 1637 the Shimabara Rebellion blamed on the Christian influence was suppressed. Portuguese traders and Jesuit missionaries faced progressively tighter restrictions, and were confined to the island of Dejima before being expelled in 1639.

The Tokugawa shogunate retreated back into a policy of isolationism identified as Sakoku (鎖国, lit. 'locked country'), forbidding contact with most outside countries. Only a limited-scale trade and diplomatic relations with China, Korea, the Ryukyu Islands, and the Dutch was maintained.[7] The Sakoku policy remained in effect until 1853 with the arrival of Commodore Perry and the "opening" of Japan.

Gunboat diplomacy

[edit]Commodore Perry's show of military force was the principal factor in negotiating a treaty allowing American trade with Japan, thus effectively ending the Sakoku period of more than 200 years in which trading with Japan had been permitted to the Dutch, Koreans, Chinese, and Ainu exclusively.

The sight of the four ships entering Edo Bay, roaring black smoke into the air and capable of moving under their own power, deeply frightened the Japanese.[8] Perry ignored the requests arriving from the shore that he should move to Nagasaki—the official port for trade with the outside—and threatened in turn to take his ships directly to Edo, and burn the city to the ground if he was not allowed to land. It was eventually agreed upon that he should land nearby at Kurihama, whereupon he delivered his letter and left.[9]

The following year, at the Convention of Kanagawa, Perry returned with a fleet of eight of the fearsome Black Ships, to demonstrate the power of the United States navy, and to lend weight to his announcement that he would not leave again, until he had a treaty. In the interim, after a debate by officials the Japanese government had decided to avoid war and agree to a treaty with the United States.[10] [8]

After roughly a month of negotiations, the shōgun's officials presented Perry with the Treaty of Peace and Amity. Perry refused certain conditions of the treaty but agreed to defer their resolution to a later time, and finally establishing formal diplomatic relations between Japan and the United States. The fleet departed, leaving behind a consul, Townsend Harris, at Shimoda to negotiate a more permanent agreement. The Harris Treaty was signed with the United States on July 29, 1858, and within five years of the signing of the Treaty of Peace and Amity, Japan had moved to sign treaties with other Western countries.[9]

In Japanese culture

[edit]The surprise and fear inspired by the first visit of the Black Ships are described in this famous kyōka (a humorous poem in 31-syllable waka form):

泰平の Taihei no 眠りを覚ます Nemuri o samasu 上喜撰 Jōkisen たった四杯で Tatta shihai de 夜も眠れず Yoru mo nemurezu

This poem is a complex set of puns (in Japanese, kakekotoba or "pivot words"). Taihei (泰平) means 'tranquil'; Jōkisen (上喜撰) is the name of a costly brand of green tea containing large amounts of caffeine; and shihai (四杯) means 'four cups', so a literal translation of the poem is:

Awoken from sleep

of a peaceful quiet world

by Jokisen tea;

with only four cups of it

one can't sleep even at night.

There is an alternative translation, based on the pivot words. Taihei can refer to the "Pacific Ocean" (太平); jōkisen also means 'steam-powered ships' (蒸気船); and shihai also means 'four vessels'. The poem, therefore, has a hidden meaning:

Breaking the halcyon slumber

of the Pacific;

The steam-powered ships,

a mere four boats are enough

to make us lose sleep at night.

Kurofune ("The Black Ships") is also the title of the first Japanese opera, composed by Kosaku Yamada and premiering in 1940, "based on the story of Tojin Okichi, a geisha caught up in the turmoil that swept Japan in the waning years of the Tokugawa shogunate".[11][12]

See also

[edit]- Treaty of Shimoda

- Russian frigate Pallada

- French Military Mission to Japan (1867-1868)

- Gunboat diplomacy

- Dutch missions to Edo

- Sakoku

- United States expedition to Korea

- Pacific Overtures, a musical about Japan's westernization in the 19th century by Stephen Sondheim

- Madama Butterfly, an opera about a US Navy officer and his Japanese wife by Giacomo Puccini

Notes

[edit]- ^ Akamatsu, Paul (1972). Meiji 1868: Revolution and Counter Revolution in Japan. Harper and Row. p. 86. ISBN 0060100443.

- ^ "Perry Ceremony Today; Japanese and U. S. Officials to Mark 100th Anniversary". New York Times. July 8, 1953.

- ^ Charles Ralph Boxer (1951). The Christian Century in Japan: 1549–1650. University of California Press. p. 91. GGKEY:BPN6N93KBJ7. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (1993). The Portuguese empire in Asia, 1500–1700: a political and economic history. University of Michigan: Longman. p. 138. ISBN 0-582-05069-3.

- ^ Rodrigues, Helena. "Nau do trato". Cham. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ M. D. D. Newitt (1 January 2005). A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion: 1400–1668. New York: Routledge. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-415-23980-6. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ^ Ronald P. Toby, State and Diplomacy in Early Modern Japan: Asia in the Development of the Tokugawa Bakufu, Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, (1984) 1991.

- ^ a b Nishiyama, Kazuo (2000-01-01). Doing Business With Japan: Successful Strategies for Intercultural Communication. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 9780824821272.

- ^ a b Beasley, William G (1972). The Meiji Restoration. Stamford University Press. p. 89. ISBN 0804708150.

- ^ Akamatsu, Paul (1972). Meiji 1868: Revolution and Counter Revolution in Japan. Harper and Row. pp. 99–100. ISBN 0060100443.

- ^ "'Black Ships' opera". New National Theatre Tokyo.

- ^ "Simon Holledge's interview with Hiroshi Oga citing the premiere of the 'Black Ships' opera". Archived from the original on 2010-05-31.

References

[edit]- Arnold, Bruce Makoto (2005). Diplomacy Far Removed: A Reinterpretation of the U.S. Decision to Open Diplomatic Relations with Japan (Thesis). University of Arizona. [1]

- Perry, Matthew Calbraith (1856). Narrative of the expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan, 1856. New York: D. Appleton and Company. Archived from the original on 2017-05-19. Retrieved 2008-08-13. [digitized by University of Hong Kong Libraries, Digital Initiatives, "China Through Western Eyes." ]

- Taylor, Bayard (1855). A visit to India, China, and Japan in the year 1853. New York: G.P. Putnam's sons. Archived from the original on 2016-03-11. Retrieved 2008-08-13. [digitized by University of Hong Kong Libraries, Digital Initiatives, "China Through Western Eyes." ]

External links

[edit]- Black Ship Festival celebrating the arrival of the Blackships and the opening of Japan to the world.

- New National Theatre Tokyo

- Opera Japonica