Erwin Piscator

Erwin Piscator | |

|---|---|

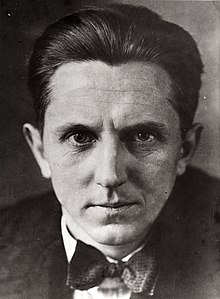

Portrait of Piscator, c. 1929 | |

| Born | Erwin Friedrich Max Piscator 17 December 1893 |

| Died | 30 March 1966 (aged 72) |

| Education | |

| Occupation(s) | Theatre director, producer |

| Known for | Founded the Dramatic Workshop at The New School for Social Research (1940). |

| Notable work | The Political Theatre (1929) |

| Style | Epic Theatre, Documentary theatre |

| Spouse(s) | Hildegard Jurczyk (m. 1919)[1] Maria Ley (m. 1937) |

| Relatives | Johannes Piscator |

| Signature | |

| |

Erwin Friedrich Maximilian Piscator (17 December 1893 – 30 March 1966) was a German theatre director and producer. Along with Bertolt Brecht, he was the foremost exponent of epic theatre, a form that emphasizes the socio-political content of drama, rather than its emotional manipulation of the audience or the production's formal beauty.[2]

Biography

[edit]Youth and wartime experience

[edit]

Erwin Friedrich Max Piscator was born on 17 December 1893 in the small Prussian village of Greifenstein-Ulm, the son of Carl Piscator, a merchant, and his wife Antonia Laparose.[3] His family was descended from Johannes Piscator, a Protestant theologian who produced an important translation of the Bible in 1600.[4] The family moved to the university town Marburg in 1899 where Piscator attended the Gymnasium Philippinum. In the autumn of 1913, he attended a private Munich drama school and enrolled at University of Munich to study German, philosophy and art history. Piscator also took Arthur Kutscher's famous seminar in theatre history, which Bertolt Brecht later also attended.[5]

Piscator began his acting career in the autumn of 1914, in small unpaid roles at the Munich Court Theatre, under the directorship of Ernst von Possart. In 1896, Karl Lautenschläger had installed one of the world's first revolving stages in that theatre.[6]

During the First World War, Piscator was drafted into the German army, serving in a frontline infantry unit as a Landsturm soldier from the spring of 1915 (and later as a signaller). The experience inspired a hatred of militarism and war that lasted for the rest of his life. He wrote a few bitter poems that were published in 1915 and 1916 in the left-wing Expressionist literary magazine Die Aktion. In summer 1917, having participated in the battles at Ypres Salient and been in hospital once, he was assigned to a newly established army theatre unit. In November 1918, when the armistice was declared, Piscator participated in the November Revolution, giving a speech in Hasselt at the first meeting of a revolutionary Soldiers' Council (Soviet).[6]

Early success in the Weimar Republic

[edit]Piscator returned to Berlin and joined the newly formed Communist Party of Germany (KPD). He left briefly for Königsberg, where he joined the Tribunal Theatre. He participated in several expressionist plays and played the student, Arkenholz, in the Ghost Sonata by August Strindberg. He joined Hermann Schüller in establishing the Proletarian Theatre, Stage of the Revolutionary Workers of Greater Berlin.[7]

In collaboration with writer Hans José Rehfisch, Piscator formed a theatre company in Berlin at the Comedy-Theater on Alte Jacobsstrasse, following the Volksbühne ("people's stage") concept. In 1922–1923 they staged works by Maxim Gorky, Romain Rolland, and Leo Tolstoy.[8] As stage director at the Volksbühne (1924–1927), and later as managing director at his own theatre (the Piscator-Bühne on Nollendorfplatz), Piscator produced social and political plays especially suited to his theories.

His dramatic aims were utilitarian — to influence voters or clarify left-wing policies. He used mechanized sets, lectures, movies, and mechanical devices that appealed to his audiences. In 1926, his updated production of Friedrich Schiller's The Robbers at the distinguished Preußisches Staatstheater in Berlin provoked widespread controversy. Piscator made extensive cuts to the text and reinterpreted the play as a vehicle for his political beliefs. He presented the protagonist Karl Moor as a substantially self-absorbed insurgent. As Moor's foil, Piscator made the character of Spiegelberg, often presented as a sinister figure, the voice of the working-class revolution. Spiegelberg appeared as a Trotskyist intellectual, slightly reminiscent of Charlie Chaplin with his cane and bowler hat. As he died, the audience heard The Internationale sung.

Piscator founded the influential (though short-lived) Piscator-Bühne in Berlin in 1927. In 1928 he produced a notable adaptation of the unfinished, episodic Czech comic novel The Good Soldier Schweik. The dramaturgical collective that produced this adaptation included Bertolt Brecht.[9] Brecht later described it as a "montage from the novel".[10] Leo Lania's play Konjunktur (Oil Boom) premiered in Berlin in 1928, directed by Erwin Piscator, with incidental music by Kurt Weill. Three oil companies fight over the rights to oil production in a primitive Balkan country, and in the process exploit the people and destroy the environment. Weill's songs from this play, such as Die Muschel von Margate, are still part of the modern repertoire of art music.[11]

In 1929 Piscator published his The Political Theatre, discussions of the theory of theatre .[12] In the preface to its 1963 edition, Piscator wrote that the book was "assembled in hectic sessions during rehearsals for The Merchant of Berlin" by Walter Mehring, which had opened on 6 September 1929 at the second Piscator-Bühne.[13] It was intended to provide "a definitive explanation and elucidation of the basic facts of epic, i.e. political theatre", which at that time "was still meeting with widespread rejection and misapprehension."[13]

Three decades later, Piscator said that:

The justification for epic techniques is no longer disputed by anyone, but there is considerable confusion about what should be expressed by these means. The functional character of these epic techniques, in other words their inseparability from a specific content (the specific content, the specific message determines the means and not vice versa!) has by now become largely obscured. So we are still standing at the starting blocks. The race is not yet on ...[14]

International work, emigration, and late productions in West Germany

[edit]

In 1931, after the collapse of the third Piscator-Bühne, Piscator went to Moscow in order to make the motion picture Revolt of the Fishermen with actor Aleksei Dikiy, for Mezhrabpom, the Soviet film company associated with the International Workers' Relief Organisation.[15] As John Willett wrote, throughout the pre-Hitler years Piscator's "commitment to the Russian Revolution was a decisive factor in all his work."[16] With Hitler's rise to power in 1933, Piscator's stay in the Soviet Union became exile.[17]

In July 1936, Piscator left the Soviet Union for France. In 1937, he married dancer Maria Ley in Paris. Bertolt Brecht was one of the groomsmen.

During his years in Berlin, Piscator had collaborated with Lena Goldschmidt on a stage adaptation of Theodore Dreiser's bestselling novel An American Tragedy; under the title The Case of Clyde Griffiths. With American Lee Strasberg as director, it had run for 19 performances on Broadway in 1936. When Piscator and Ley subsequently immigrated to the United States in 1939, Piscator was invited by Alvin Johnson, the founding president of The New School, to establish a theatre workshop. Among Piscator's students at this Dramatic Workshop in New York were Bea Arthur, Harry Belafonte, Marlon Brando, Tony Curtis, Ben Gazzara, Judith Malina, Walter Matthau, Rod Steiger, Elaine Stritch, Eli Wallach, Jack Creley, and Tennessee Williams.[18]

Established in New York, Erwin and Maria Ley-Piscator lived at 17 East 76th Street, an Upper East Side townhome, sometimes remembered as the Piscator House.[19]

After World War II and the break-up of Germany, Piscator returned to West Germany in 1951 due to McCarthy era political pressure in the United States against former communists in the arts.[20] In 1962 Piscator was appointed manager and director of the Freie Volksbühne in West Berlin. To much international critical acclaim, in February 1963 Piscator premièred Rolf Hochhuth's The Deputy, a play "about Pope Pius XII and the allegedly neglected rescue of Italian Jews from Nazi gas chambers."[21] Until his death in 1966, Piscator was a major exponent of contemporary and documentary theatre. Piscator's wife, Maria Ley, died in New York City in 1999.

Effects on theatre

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

| In lieu of private themes we had generalisation, in lieu of what was special the typical, in lieu of accident causality. Decorativeness gave way to constructedness, Reason was put on a par with Emotion, while sensuality was replaced by didacticism and fantasy by documentary reality. |

| Erwin Piscator, 1929.[22] |

Piscator's contribution to theatre has been described by theatre historian Günther Rühle as "the boldest advance made by the German stage" during the 20th century.[23] Piscator's theatre techniques of the 1920s — such as the extensive use of still and cinematic projections from 1925 on, as well as complex scaffold stages — had an extensive influence on European and American production methods. His dramaturgy of contrasts led to sharp political satirical effects and anticipated the commentary techniques of epic theatre.[citation needed]

In the Federal Republic of Germany, Piscator's interventionist theatre model enjoyed a late second zenith. From 1962 on, Piscator produced several works that dealt with trying to come to terms with the Germans' Nazi past and other timely issues; he inspired mnemonic and documentary theatre in those years until his death. Piscator's stage adaptation of Leo Tolstoy's novel War and Peace[24] has been produced in some 16 countries since 1955, including three productions in New York City.[citation needed]

Legacy and honors

[edit]

In 1980, a monumental sculpture by Scottish artist Eduardo Paolozzi was dedicated to Piscator in central London.[25] In the fall of 1985, an annual Erwin Piscator Award was inaugurated in New York City, the adopted home of Piscator's widow Maria Ley. Additionally, a Piscator Prize of Honors has been annually awarded to generous patrons of art and culture in commemoration of Maria Ley since 1996. The host of the Erwin Piscator Award is the international non-profit organisation "Elysium − between two continents" that aims to foster artistic and academic dialogue and exchange between the United States and Europe. In 2016, a Piscator monument was erected in his birthplace of Greifenstein-Ulm.[26]

Piscator's artistic papers are held by the archive of the Academy of Arts, Berlin (since 1966) and the Southern Illinois University Carbondale (Morris Library, since 1971).[27]

Broadway productions

[edit]- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Nathan the Wise (Belasco Theatre, April 1942)

- Irving Kaye Davis, The Last Stop (Ethel Barrymore Theatre, September 1944)

Films

[edit]- Revolt of the Fishermen (Восстание рыбаков). Director: Erwin Piscator, Screenplay: Georgi Grebner, Willy Döll, Producer: Mikhail Doller, USSR 1932–1934.

Works

[edit]- Piscator, Erwin. 1929. The Political Theatre. A History 1914–1929. Translated by Hugh Rorrison. New York: Avon, 1978. ISBN 978-0-380401-88-8 (= London: Methuen, 1980. ISBN 978-0-413335-00-5).

- The ReGroup Theatre Company (ed.): The "Lost" Group Theatre Plays. Volume 3. The House of Connelly, Johnny Johnson, & Case of Clyde Griffiths. By Paul Green and Erwin Piscator. Prefaces by Judith Malina & William Ivey Long. New York, NY: CreateSpace, 2013. ISBN 978-1-484150-13-9.

- Tolstoy, Leo. War and Peace. Adapted for the Stage by Alfred Neumann, Erwin Piscator, and Guntram Prüfer. English adaptation by Robert David MacDonald. Preface by Bamber Gascoigne. London: Macgibbon & Kee, 1963.

Literature

[edit]- Connelly, Stacey Jones. Forgotten Debts: Erwin Piscator and the Epic Theatre. Bloomington: Indiana University 1991.

- Innes, Christopher D. Erwin Piscator's Political Theatre: The Development of Modern German Drama. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1972.

- Ley-Piscator, Maria. The Piscator Experiment. The Political Theatre. New York: James H. Heineman 1967. ISBN 0-8093-0458-9.

- Malina, Judith. The Piscator Notebook. London: Routledge Chapman & Hall 2012. ISBN 0-415-60073-1.

- McAlpine, Sheila. Visual Aids in the Productions of the First Piscator-Bühne, 1927–28. Frankfurt, Bern, New York etc.: Lang 1990.

- Probst, Gerhard F. Erwin Piscator and the American Theatre. New York, San Francisco, Bern etc. 1991.

- Rorrison, Hugh. Erwin Piscator: Politics on the Stage in the Weimar Republic. Cambridge, Alexandria VA 1987.

- Wannemacher, Klaus. "Moving Theatre Back to the Spotlight: Erwin Piscator’s Later Stage Work". In: The Great European Stage Directors. Vol. 2. Meyerhold, Piscator, Brecht. Ed. by David Barnett. London etc.: Bloomsbury (Methuen Drama) 2018, pp. 91–129. ISBN 1-474-25411-X.

- Willett, John. The Theatre of Erwin Piscator: Half a Century of Politics in the Theatre. London: Methuen 1978. ISBN 0-413-37810-1.

External links

[edit]- Erwin Piscator at IMDb

- Website on Erwin Piscator, including "Annotated Erwin Piscator Bibliography" with more than 1300 title entries (German)

- Erwin Piscator Papers, 1930–1971 Archived 25 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Special Collections Research Center

- Information on the annual Erwin Piscator Award

- Photo of Piscator at Find a Grave

References

[edit]- ^ erwin-piscator.de (in German)

- ^ Piscator, Erwin. Grolier Encyclopedia of Knowledge, volume 15, copyright 1991. Grolier Inc., ISBN 0-7172-5300-7

- ^ Willett, John. 1978. The Theatre of Erwin Piscator: Half a Century of Politics in the Theatre. London: Methuen. pg 13.

- ^ Willett (1978, 42).

- ^ Willett (1978, 43)

- ^ a b Willett (1978, 43).

- ^ Braun, Edward (1986). The Director & The Stage: From Naturalism to Grotowski. London: A & C Black. ISBN 978-1-4081-4924-9.

- ^ Willett (1978, 15–16, 46–47).

- ^ Willett (1978, 90–95).

- ^ See Brecht's Journal entry for 24 June 1943. Brecht claimed in his Journal entry to have written the adaptation, but Piscator contested that; the manuscript bears the names "Brecht, Gasbarra, Piscator, G. Grosz" in Brecht's handwriting (John Willett. 1978. Art and Politics in the Weimar Period: The New Sobriety 1917–1933. New York: Da Capo Press, 1996, 110). Brecht wrote another Schweik drama in 1943, Schweik in the Second World War.

- ^ The Kurt Weill Foundation for Music's Documentation on Muschel von Margate

- ^ Piscator (1929).

- ^ a b Piscator (1929, vi).

- ^ Piscator (1929, vii).

- ^ Gerhard F. Probst: Erwin Piscator and the American Theatre. New York etc.: Peter Lang, 1991, p. 7. ISBN 0-8204-1591-X

- ^ John Willett: Introduction, in: Erwin Piscator. 1893–1966. An Exhibition by the Archiv der Akademie der Künste Berlin, in cooperation with the Goethe Institute. Ed. by Walter Huder. London 1979, p. 1–4, p.1.

- ^ Hermann Haarmann: "Politisches Theater im Geiste der Polis. Die späte Heimkehr des Erwin Piscator". In: Freie Volksbühne Berlin 1890–1990. Beiträge zur Geschichte der Volksbühnenbewegung in Berlin. Ed. by Dietger Pforte. Berlin: Argon 1990. Pp. 195–210, p. 195.

- ^ Willett (1978, 166).

- ^ Art, Sebastian Izzard Asian. "MARCH 2004 and APRIL 2004". Sebastian Izzard Asian Art. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ Alexander Stephan: Im Visier des FBI. Deutsche Exilschriftsteller in den Akten amerikanischer Geheimdienste. Stuttgart, Weimar 1995, p. 373.

- ^ Gerhard F. Probst: Erwin Piscator and the American Theatre. New York etc.: Peter Lang, 1991, p. 19. ISBN 0-8204-1591-X

- ^ From a speech given on 25 March 1929, and reproduced in Schriften 2 p.50; Quoted by Willett (1978, 107).

- ^ Günther Rühle: "Erwin Piscator: Dream and Achievement", in: Erwin Piscator. 1893–1966. An Exhibition by the Archiv der Akademie der Künste Berlin, in cooperation with the Goethe Institute. Ed. by Walter Huder. London 1979, p. 12–19, p. 16.

- ^ Leo Tolstoy. War and Peace. Adapted for the stage by Alfred Neumann, Erwin Piscator and Guntram Prüfer. London: Macgibbon & Kee 1963.

- ^ Piscator – The Making of Eduardo Paolozzi's Euston Square Sculpture. Director: Murray Grigor. Inverkeithing: Everallin 1984 (documentary film).

- ^ Erwin Piscator Monument (in German), Greifenstein-Ulm website

- ^ Archive Performing Art at Academy of Arts, Berlin (in German), website, Erwin Piscator Papers, Southern Illinois University Carbondale, website Archived 25 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- 1893 births

- 1966 deaths

- People from Lahn-Dill-Kreis

- People from Hesse-Nassau

- German Marxists

- German theatre directors

- German theatre managers and producers

- Modernist theatre

- German Army personnel of World War I

- Refugees from Nazi Germany in the Soviet Union

- Commanders Crosses of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Burials at the Waldfriedhof Zehlendorf