Gil Kane

| Gil Kane | |

|---|---|

Kane at the 1976 San Diego Comic-Con | |

| Born | Eli Katz April 6, 1926 Riga, Latvia |

| Died | January 31, 2000 (aged 73) Miami, Florida, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Area(s) | Writer, Penciller |

| Pseudonym(s) | Scott Edward, Gil Stack, Stack Til, Stacktil, Pen Star, Phil Martell |

Notable works | Green Lantern Atom Spider-Man Blackmark Adam Warlock |

| Awards | National Cartoonists Society Award (1971, 1972, 1975, 1977) Shazam Award (1971) Inkpot Award (1975) |

Gil Kane (/ɡɪl keɪn/; born Eli Katz /kæts/, Latvian: Elija Kacs; April 6, 1926 – January 31, 2000) was a Latvian-born American comics artist whose career spanned the 1940s to the 1990s and virtually every major comics company and character.

Kane co-created the modern-day versions of the superheroes Green Lantern and the Atom for DC Comics, and co-created Iron Fist and Adam Warlock with Roy Thomas for Marvel Comics. He was involved in the anti-drug storyline in The Amazing Spider-Man #96–98, which, at the behest of the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, bucked the then-prevalent Comics Code Authority to depict drug abuse, and ultimately spurred an update of the Code. Kane additionally pioneered an early graphic novel prototype, His Name Is... Savage, in 1968, and a seminal graphic novel, Blackmark, in 1971.

In 1997, he was inducted into both the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame and the Harvey Award Jack Kirby Hall of Fame.

Biography

[edit]Early life and career

[edit]Gil Kane was born Eli Katz (Latvian: Elija Kacs) on April 6, 1926, in Latvia[1] to a Jewish family that immigrated to the U.S. in 1929, settling in Brooklyn, New York City. His father was a struggling poultry merchant.[2] Kane attended high school at Manhattan's School of Industrial Art,[3] but left in his senior year[3] when he saw an opportunity to work at MLJ Comics (later Archie Comics). He recalled in a 1996 interview,

[F]rom the time I was 15, I was going up to the comics offices. ... My first job came the next year at 16. During my summer vacation [between years of high school], I went up and got a job working at MLJ in 1942 ... I was in my last year in high school [when I left]. I was 16 and I'd already started my last year but I'd already gotten my job the summer before at MLJ, so I didn't want to give up my job. I quit school in the last grade.[4]

Until being fired after three weeks, Kane worked in production, "putting borders on pages. The letterers would only put in the lettering, not the balloons, so I would put in the borders, balloons, and I'd finish up artwork—whatever had to be done on a lesser scale."[4] Within "a couple of days" of being let go, "I got a job with Jack Binder's agency. Jack Binder had a loft on Fifth Avenue and it just looked like an internment camp. There must have been 50 or 60 guys up there, all at drawing tables. You had to account for the paper that you took." Kane began penciling professionally there, but, "They weren't terribly happy with what I was doing. But when I was rehired by MLJ three weeks later, not only did they put me back into the production department and give me an increase, they gave me my first job, which was 'Inspector Bentley of Scotland Yard' in Pep Comics, and then they gave me a whole issue of The Shield and Dusty, one of their leading books".[4] He would also do spot illustrations for other studios.[2]

His earliest known credit is inking Carl Hubbell on the six-page Scarlet Avenger superhero story "The Counterfeit Money Code" in MLJ's Zip Comics #14 (cover-dated May 1941), on which he signed the name "Gil Kane".[5] Other early credits include some issues of the company's Pep Comics, sometimes under pseudonyms including Stack Til and Stacktil, and, in conjunction with artist Pen Shumaker, Pen Star.[5][6][7] He even used his birth name on rare occasions, including on at least one story each in the Temerson / Helnit / Continental publishing group's Terrific Comics and Cat-Man Comics.[5]

In 1944 he did his first work for the future Marvel Comics, as one of two inkers on the 28-page "The Spawn of Death" in the wartime kid-gang comic Young Allies #11 (March 1944), and the future DC Comics, as the uncredited ghost artist for Jack Kirby on the Sandman superhero story "Courage a la Carte" in Adventure Comics #91 (May 1944).[5] That same year Kane either was drafted[3] or enlisted in the Army and served in the World War II Pacific theater of operations.[2][8] After 19 months in the service, he returned to in December 1945. All-American Publications editor Sheldon Mayer hired him in 1947, for a stint that lasted six months.[3] He contributed again to the "Sandman" feature in Adventure Comics and, as penciler Gil Stack and inker Phil Martel, to the "Wildcat" feature in Sensation Comics.[5] Around this time, he said, he "worked with director Garson Kanin when he was involved in TV", drawing storyboards.[8]

In 1949, Kane began a longtime professional relationship with Julius Schwartz, an editor at National Comics, the future DC Comics.[3] Kane drew stories for several DC series in the 1950s including All-Star Western[9] and The Adventures of Rex the Wonder Dog.[10]

Silver Age of Comic Books

[edit]

In the late 1950s, freelancing for DC Comics precursor National Comics, Kane illustrated works in what fans and historians call the Silver Age of Comic Books, creating character designs for the modern-day version of the 1940s superhero Green Lantern,[11] for which he pencilled most of the first 75 issues of the reimagined character's comic. Comics historian Les Daniels praised Kane's work on the character, stating "The design was part of an approach that emphasized grace as well as strength, an approach especially notable in Kane's flying scenes ... Green Lantern appeared to soar effortlessly across the cosmos."[12] DC Comics writer and executive Paul Levitz noted in 2010 that Kane "modeled the Guardians on Israeli founding father David Ben-Gurion, even as the human figures in the cast tended to mimic Kane's own tall, elongated build."[13] Kane and writer John Broome's stories for the Green Lantern series included transforming Hal Jordan's love interest, Carol Ferris, into the Star Sapphire in issue #16.[14] Black Hand, a character featured prominently in the "Blackest Night" storyline in 2009–2010, debuted in issue #29 (June 1964) by Broome and Kane.[15] The creative team created Guy Gardner in the story "Earth's Other Green Lantern!" in issue #59 (March 1968).[16]

Kane similarly co-created an updated version of the Atom with writer Gardner Fox.[17] Kane — who by 1960 was living in Jericho, New York, on Long Island[18] — also drew the youthful superhero team the Teen Titans, a revival of Plastic Man,[19] and, in the late 1960s, such short-lived titles as Hawk and Dove and the licensed-character comic Captain Action, based on the action figure. Kane and Marv Wolfman created an origin for Wonder Girl in Teen Titans #22 (July–Aug. 1969) which introduced the character's new costume.[20]

He briefly freelanced some Hulk stories in Marvel Comics' Tales to Astonish, first under the pseudonym Scott Edward and then in his own name, defying the practice in which DC artists moonlighting at Marvel used pseudonyms.[21] He and writer/editor Stan Lee introduced the Abomination as an enemy of the Hulk in Tales to Astonish #90 (April 1967).[22] Kane also freelanced in the 1960s for Tower Comics' T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents, a superhero/espionage title,[23] as well as the "Tiger Boy" strip for Harvey Comics. Kane then found a home at Marvel, eventually becoming the regular penciller for The Amazing Spider-Man, succeeding John Romita in the early 1970s, and becoming the company's preeminent cover artist through that decade. Kane's first Spider-Man storyline culminated in the death of supporting character George Stacy.[24]

During that run, he and editor-writer Stan Lee produced in 1971 a three-issue story arc in The Amazing Spider-Man #96-98 (May–July 1971) that marked the first challenge to the industry's self-regulating Comics Code Authority since its inception in 1954. The Code forbade mention of drugs, even in a negative context. However, Lee and Kane created an anti-drug storyline conceived at the behest of the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, and upon not receiving Code Authority approval, Marvel published the issues without the Code seal on their covers.[25] The comics met with such positive reception and high sales that the industry's self-censorship was undercut, and the Code soon afterward was revamped.[26] Another landmark in Kane's Spider-Man run was the arc "The Night Gwen Stacy Died" in issues #121–122 (June–July 1973), in which Spider-Man's girlfriend Gwen Stacy, as well as the long-time villain Green Goblin were killed, an unusual occurrence at the time.[27]

With writer Roy Thomas, Kane helped revise the Marvel Comics version of Captain Marvel,[28] and revamped a preexisting character as Adam Warlock.[29] Kane and Thomas co-created the martial arts superhero Iron Fist,[30] and Morbius the Living Vampire.[31] Kane and writer Gerry Conway transformed John Jameson, an incidental character in The Amazing Spider-Man series, into the Man-Wolf.[32]

Conway, Kane's collaborator on the death-of-Gwen-Stacy storyline and elsewhere, described Kane in 2009 as

... a marvelous draftsman and an idiosyncratic storyteller. I quickly learned that working with him Marvel-style (that's when a writer gives the artist a plot and the artist breaks down the story, panel by panel and page by page) could sometimes result in lopsided storytelling; the first two-thirds of a story would be leisurely paced, and the last third would be hellbent-for-leather as Gil tried to make up for loose storytelling in the first half [sic]. So after doing a few stories with him in my usual loosely plotted style, I began giving him tighter plots, indicating where the story had to be by such-and-such a page. He seemed to prefer this, and I'm generally happier with the later stories we did together than the first few.[33]

Pioneering new formats

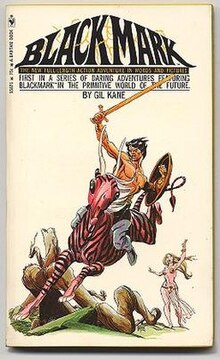

[edit]Kane's side projects include two long works that he conceived, plotted and illustrated, with scripting by Archie Goodwin (writing under the pseudonym of Robert Franklin): His Name Is... Savage (Adventure House Press, 1968), a self-published, 40-page, magazine-format comics novel; and Blackmark (1971), a science-fiction/sword-and-sorcery paperback published by Bantam Books and one of the earliest examples of the graphic novel, a term not in general use at the time. Howard Chaykin served as Kane's assistant during the production of Blackmark and would call Kane "the most influential male" in his life.[34]

Later career

[edit]During the 1970s and 1980s, Kane did character designs for various Hanna-Barbera[23] and Ruby-Spears[35] animated TV series including The Centurions which he co-created with Jack Kirby. In 1974 he contributed to redesigning the obscure Marvel Comics character the Cat into Tigra,[36] and three years later created the newspaper daily comic strip Star Hawks with writer Ron Goulart. The strip, which ran through 1981,[37] was known for its experimental use of a two-tier format during the first years. During this decade he also illustrated paperback and record-album covers, drew model box art, and co-wrote, with John Jakes, the 1980 novel Excalibur![38] He drew the John Carter, Warlord of Mars series for Marvel beginning in June 1977.[39]

In 1971, Kane met Michel "Greg" Regnier, then the editor of French-Belgian comics anthology Tintin Weekly. He ended up creating a science fiction/fantasy tale called Jason Drum, about an astronaut stranded on a sword and sorcery world. The series debuted in Tintin weekly, making the cover of #202 (July 1979). Due to a medical emergency Kane reached out to Joe Staton to help with layouts and, starting with Tintin #205, uninked penciled pages were sent to France. Belgian artist Franz inked five pages of Kane’s pencils and pencilled and inked the last pages of the story himself (in #206 and 207 [Aug. ’78]). After his recovery, Kane lost contact with Tintin. In 2006 Kane´s friend Gary Groth and publisher at Fantagraphics discovered that Kane did evidently finish the Jason Drum project with 44 fully inked pages with dialogue. The project had never been published in English, but the original 27 page version assisted by Staton and Franz was published in some other languages including Swedish (as back-up in Lee Falk's The Phantom in 1980).[40][41]

Kane was one of the artists on the double-sized Justice League of America #200 (March 1982).[42] and had a brief run on The Micronauts series in 1982 [43] In the early 1980s, he shared regular art duties on the Superman feature in Action Comics with Curt Swan and contributed to the 1988 Superman animated TV series.[23] The Brainiac character, a nemesis of Superman, was revised by Kane and Marv Wolfman in Action Comics #544 (June 1983).[44] He was one of the contributors to the DC Challenge limited series in 1986.[45] Kane was the artist on the early Green Lantern serial in the short-lived anthology Action Comics Weekly from issues #601–605 with writer James Owsley,[46] and illustrated the Nightwing cover for issue #627 in 1988. He returned to drawing the Atom in the Sword of the Atom limited series, a collaboration with writer Jan Strnad.[47] In 1989–1990 Kane illustrated a comic-book adaptation of Richard Wagner's mythological opera epic The Ring of the Nibelung.[37]

During the following decade, Kane drew for publishers including Topps Comics, for which he illustrated a miniseries adaptation of the film Jurassic Park; Malibu Comics, for which he and writer Steven Grant created the superhero Edge for a 1994–95 miniseries; Awesome Entertainment, in which he illustrated Alan Moore's four-page Kid Thunder story "Judgment Day: 1868" in Judgment Day Alpha #1 (June 1997); and DC, for which he drew several Superman stories. He was one of the many creators who contributed to the Superman: The Wedding Album one-shot wherein the title character married Lois Lane.[48] He and his former apprentice Howard Chaykin worked together again on a three-part story for Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight #24–26 (Nov. 1991 – Jan. 1992)[49] and the Superman: Distant Fires one-shot (1998).[50]

Kane collaborated with writer Mark Waid on The Life Story of the Flash graphic novel.[51] As well during that decade, he designed the set of the 1997 Santa Monica Playhouse production of the play Lovely!.[52]

Though his last full comic during his lifetime was Awesome's 40-page Judgment Day: Aftermath #1 (March 1998) — written by Moore and featuring the characters and teams Glory, Spacehunter, Youngblood and others in individual tales — his final narrative works, all for DC, were penciling the two-page "Antibiotics: The Killers That Save Lives" in Celebrate the Century: Super Heroes Stamp Album #5 (1999); portions of seven pages and the cover, all shared with humor artist Sergio Aragonés, of DC's Fanboy #2 (April 1999); and a two-page pastiche of 1970s Hostess Fruit Pie superhero ads, "The Star Sheriffs", in Green Lantern Secret Files and Origins #2 (Sept. 1999). His last published comics art during his lifetime was a one-page illustration in Dark Horse Comics' Sin City: Hell and Back #4 (Oct. 1999).[5] Posthumously published was his final completed work, the two-issue Green Lantern / Atom story in Legends of the DC Universe #28–29 (May–June 2000); and four years later, the final issue, drawn in the mid-1990s, of Malibu's planned four-issue miniseries Edge, as part of the iBooks hardcover collection The Last Heroes.[5][53]

Death and legacy

[edit]He remained active as an artist until his death on January 31, 2000, in Miami, Florida from complications of lymphoma.[1] He was survived by his second wife, Elaine;[54][55] as well as a son and two stepchildren,[38] Scott, Eric and Beverly.[1] For a time the family lived in Wilton, Connecticut,[8] where he was drama chairman of the Wilton Arts Council.[56] His final home was Aventura, Florida.[1]

An homage to Kane and to writer John Broome appears in In Darkest Night, a novelization of the Justice League animated series. The book refers to the Kane/Broome Institute for Space Studies in Coast City.[57] The Broome Kane Galaxy in Green Lantern: Emerald Knights is named for him and John Broome. Writer Alan Moore made Kane a character in Awesome Comics' Judgment Day: Aftermath which Kane illustrated.[52]

While he was alive, Kane was made the lead character in writer Mike Friedrich's story "His Name Is... Kane" (a play on Kane's His Name Is... Savage) in DC Comics' supernatural anthology House of Mystery #180 (June 1969). In the six-and-a-half-page tale, penciled by Kane and inked by Wally Wood, frustrated comic-book artist Gil Kane kills his House of Mystery editor, Joe Orlando. Orlando, also an artist, and Friedrich exact revenge by drawing Kane into artwork that is then framed and mounted in the house.[58][59]

Kane's work has been extensively reprinted. Marvel Comics released Marvel Visionaries Gil Kane in 2002[60] and DC Comics published Adventures of Superman: Gil Kane in 2013.[61] IDW Publishing released an "artist's edition", a reproduction of the original art, of Kane's Spider-Man work in 2012.[62][63]

Awards and exhibitions

[edit]Kane received numerous awards over the years, including the 1971, 1972, and 1975 National Cartoonists Society Awards for Comic Books: Story, and the group's "Newspaper Strip: Story Strip Award" for 1977 for Star Hawks.[64]

He also received the comic book industry's Shazam Award for Special Recognition in 1971 "for Blackmark, his paperback comics novel" and was given an Inkpot Award in 1975.[65] Kane was named to both the Eisner Award Hall of Fame[66] and the Harvey Award Jack Kirby Hall of Fame in 1997.[67]

Work by Kane was part of the 1995 Muckenthaler Cultural Center exhibit "KAPOW: A Showcase of Superheroes", in Fullerton, California.[52]

Bibliography

[edit]Adventure House Press

[edit]- His Name Is... Savage (1968)

DC Comics

[edit]- Action Comics (Superman) #539–541, 544–546, 551–554, 642 (four pages only), 715; (Green Lantern) #601–605, (Nightwing cover art) #627 (1983–95)

- Adventure Comics #92–99, 101–102, 425 (1944–46, 1972)

- Adventures of Rex the Wonder Dog #3–46 (1952–59)

- All-American Men of War #12 (1954)

- All-American Western #107–108, 114–115, 117–126 (1949–52)

- All Star Comics #53 (1950)

- All-Star Western #58–75, 80–119 (1951–61)

- All-Star Western vol. 2 #3–4, 6, 8 (1970–71)

- Atari Force #3, 5 (1982–83)

- Atom #1–37 (1962–68)

- Batman #208 (1969)

- Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight #24–26 (1991–92)

- Blue Beetle #22 (1988)

- Blue Devil #7 (1984)

- Boy Commandos #30–31, 35 (1948–49)

- Captain Action #2–5 (1968–69)

- DC Challenge #4 (1986)

- DC Comics Presents (Johnny Thunder) #28; (Rex the Wonder Dog) #35; (Superman and Shazam!) Annual #3 (1980–84)

- Detective Comics (Batman and Robin) #371, 374; (Elongated Man) #368, 370, 372–373; (Batgirl) #384–385, 388–389, 392–393, 396, 401, 406–407; (Robin) #390–391, 394, 398–399, 402–403; (Catwoman) #520 (1967–82)

- Doomsday Annual #1 (1995)

- Falling in Love #3, 5, 32, 70, 73 (1956–65)

- Fanboy #2 (1999)

- The Flash #195, 197–199 (1970)

- Forbidden Tales of Dark Mansion #13 (1973)

- Girls' Love Stories #32 (1954)

- Girls' Romances #25, 29, 107 (1954–65)

- Green Lantern, vol. 2, #1–61, 68–75, 156; (Green Lantern Corps) #177 (1960–70, 1982–84)

- Green Lantern Corps #223–224 (1988)

- Green Lantern Secret Files and Origins #2 (1999)

- Hawk and the Dove #3–6 (1968–69)

- Hopalong Cassidy #123–135 (1957–59)

- House of Mystery #180, 184, 196, 253, 300 (1969–82)

- House of Secrets #85 (1970)

- Jimmy Wakely #6–11, 15–18 (1950–52)

- Justice League of America #200 (six-pages only)(1982)

- Legends of the DC Universe (Green Lantern and the Atom) #28–29 (2000)

- Life Story of the Flash HC (1997)

- Metal Men #30–31 (1968)

- Mr. District Attorney #15 (1950)

- Mystery in Space #3–5, 12–16, 18–43, 47, 50, 53–54, 56, 59–61, 67, 100–102 (1951–61, 1965)

- Our Army at War #1, 3 (1952)

- Plastic Man #1 (1966)

- Power of Shazam! #14, 19 (this issue with Joe Staton) (1996)

- Ring of the Nibelung #1–4 (miniseries) (1990)

- Secret Hearts #22, 35, 95 (1954–64)

- Secret Origins vol. 2 (Blue Beetle) #2; (Midnight) #28 (1986–88)

- Sensation Comics #70–74, 89 (Wildcat); #101, 103–106 (Astra); #109 (1947–52)

- Sensation Mystery #115 (1953)

- Showcase (Green Lantern) #22–24; (the Atom) #34–36 (1959–62)

- Star-Spangled Comics #31–32 (1944)

- Star Spangled War Stories #55, 169 (1957–73)

- Static #31 (1996)

- Strange Adventures #7–8, 11, 16, 25–29, 31, 35–81, 83, 106, 108, 113, 124–125, 130, 138, 146, 148, 151, 153–154, 15, 159, 173–174, 176, 179, 182, 184–186; (Adam Strange) #222 (1951–70)

- Super DC Giant #S-15 (1970)

- New Adventures of Superboy (comic book) (covers only) 32, 33, 35, 39, 41, 42, 43–49 (1982–84)

- Superman (Fabulous World of Krypton) #367, 375; (Superman 2021) #372 (1982)

- Superman vol. 2 #99, 101–103 (1995)

- Superman: Blood of My Ancestors (with John Buscema) (2003, posthumous)

- Superman: Distant Fires (1998)

- Superman Special #1–2 (1983–84)

- Superman: The Wedding Album (among other artists) (1996)

- Sword of the Atom #1–4 (miniseries), Special #1–2 (1983–85)

- Tales of the Green Lantern Corps Annual #1 (1985)

- Tales of the Unexpected #88 (1965)

- Talos of the Wilderness Sea (1987)

- Teen Titans #19, 22–24 (1969)

- Teen Titans vol. 2 #12 (1997)

- Time Warp #2 (1979)

- Vigilante #12–13 (1984)

- Weird Mystery Tales #10 (1974)

- Weird Western Tales #15, 20 (1972–73)

- Western Comics #44–76 (Nighthawk); #77–85 (Matt Savage) (1954–61)

- Witching Hour #12 (1970)

- World's Finest Comics (Green Arrow and Black Canary) #282–283; (Captain Marvel) #282 (1982)

- Young Romance #175 (1971)

Le Lombard

[edit]- Tintin (magazine) (Jason Drum) #202 – 205 (1979)

Malibu Comics

[edit]- Edge #1–3 (1994)

Marvel Comics

[edit]- Adventure into Fear (Morbius) #21 (1974)

- Adventures into Terror #13, 17, 21 (1952–1953)

- Adventures into Weird Worlds #12 (1952)

- The Amazing Spider-Man #89–92, 96–105, 120–124, 150; Annual #10, 24 (1970–76, 1990)

- Astonishing Tales (Ka-Zar) #11, 15 (1972)

- Captain America #145 (with John Romita Sr.) (1972)

- Captain Marvel #17–21 (1969–70)

- Conan the Barbarian #12, 17–18, 127–134, Annual #6; Giant-Size #1–4 (1971–1982)

- Creatures on the Loose (Gullivar Jones) #16–17 (1972)

- Daredevil #141, 146–148, 151 (1977–78)

- Deadly Hands of Kung Fu (Sons of the Tiger) #23 (1976)

- Ghost Rider #21 (1976)

- Giant-Size Defenders #2 (1974)

- Giant-Size Super-Heroes #1 (Spider-Man, the Man-Wolf, and Morbius) (1974)

- Girl Confessions #31 (1952)

- Inhumans #5–7 (1976)

- The Invincible Iron Man #43–50 (1972)

- John Carter, Warlord of Mars #1–10 (1977–78)

- Journey into Mystery, vol. 2, #1–2 (1972)

- Jungle Action, vol. 2 (Black Panther) #9 (1974)

- Ka-Zar the Savage #11–12, 14 (Zabu backup stories) (1982)

- Kull and the Barbarians #2 (1975)

- Lovers #58 (1954)

- Marvel Comics Presents (Two-Gun Kid) #116 (1992)

- Marvel Fanfare (Mowgli) #9-11 (1983)

- Marvel: Heroes & Legends #2 (1997)

- Marvel Premiere (Adam Warlock) #1–2; (Iron Fist) #15 (1972–74)

- Marvel Preview (Blackmark) #17 (1978)

- Marvel Tales #117 (1953)

- Marvel Team-Up (Spider-Man team-ups) #4–6, 13–14, 16–19, 23 (1972–74)

- Marvel Two-in-One (The Thing team-ups) #1–2 (1974)

- Men's Adventures #21 (1953)

- Micronauts #38, 40–45 (1982)

- Monsters Unleashed #3 (1973)

- My Own Romance #27 (1953)

- Mystic #8, 24 (1952–53)

- New Warriors Annual #4 (1994)

- Savage Sword of Conan #1–4, 8, 47, 63–65, 67, 85–86 (1974–83)

- Savage Tales (Conan) #4 (with Neal Adams) (1974)

- Scarlet Spider #1 (1995)

- Spider-Man #63 (1995)

- Star Trek #15 (1981)

- Supernatural Thrillers #3 (1973)

- Suspense #14 (1952)

- Tales of Suspense (Captain America) #88–91 (1967)

- Tales to Astonish (Hulk) #76, 88–91 (1966–67)

- Thor #318 (1982)

- Vampire Tales (Morbius, the Living Vampire) #5 (1974)

- War Comics #19 (1953)

- Warlock #1–5 (1972–73)

- Web of Spider-Man Annual #6 (1990)

- Werewolf by Night #11–12 (1973)

- What If? (Avengers) #3, (Spider-Man) #24 (1977–80)

- Worlds Unknown #1–2 (1973)

- Young Allies #11 (1944)

Quality Comics

[edit]- Doll Man #19 (1948)

Tower Comics

[edit]- Noman #1 (1966)

- T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents #1, 5, 14, 16 (1965–67)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Martin, Douglas (February 3, 2000). "Gil Kane, Comic-Book Artist, Is Dead at 73". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009.

- ^ a b c Sedlmeier, Cory (ed.). Marvel Masterworks: The Incredible Hulk Volume 2. Marvel Entertainment. p. 244.

- ^ a b c d e Herman, Daniel (2004). Silver Age: The Second Generation of Comic Artists. Neshannock Township, Lawrence County, Pennsylvania: Hermes Press. p. 68. ISBN 1-932563-64-4.

- ^ a b c "Interview with Gil Kane, Part I". The Comics Journal (186). Seattle, Washington: Fantagraphics Books. April 1996. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Note: The New York Times obituary and the Hulk Marvel Masterworks capsule biography erroneously say he left school at age 15.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gil Kane at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Bails, Jerry; Ware, Hames, eds. "Kane, Gil". Who's Who of American Comic Books, 1928–1999. Archived from the original on March 16, 2013.

{{cite web}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Case of the Laughing Corpse" (Pen Star credit) at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ a b c Kane, Gil. "Gil Kane". National Cartoonists Society. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ^ Irvine, Alex; Dolan, Hannah, ed. (2010). "1950s". DC Comics Year By Year A Visual Chronicle. London, United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-7566-6742-9.

With work by artists Gil Kane, Carmine Infantino, and Alex Toth and writer Robert Kanigher, among others, All-Star Western would run for ten years.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Irvine "1950s" in Dolan, p. 71

- ^ Irvine "1950s" in Dolan, p. 95: "DC had decided to revamp a number of characters to inject new life into the genre. Writer John Broome and artist Gil Kane ensured that Green Lantern got his turn in October's Showcase #22."

- ^ Daniels, Les (1995). "Green Lantern Lit Again Comics Get Cosmic Consciousness". DC Comics: Sixty Years of the World's Favorite Comic Book Heroes. New York, New York: Bulfinch Press. p. 124. ISBN 0821220764.

- ^ Levitz, Paul (2010). "The Silver Age 1956–1970". 75 Years of DC Comics The Art of Modern Mythmaking. Cologne, Germany: Taschen. p. 252. ISBN 9783836519816.

- ^ McAvennie, Michael "1960s" in Dolan, p. 105: "In his first confrontation with Star Sapphire, Green Lantern didn't realize he was actually battling his lady love, Carol Ferris. As was revealed by scribe John Broome and artist Gil Kane ..."

- ^ McAvennie "1960s" in Dolan, p. 111: "Scribe John Broome and artist Gil Kane split this issue into two stories ... William Hand, introduced in a cameo by Kane, informed readers of a power light he invented to collect remnant energy from Green Lantern's power ring."

- ^ McAvennie "1960s" in Dolan, p. 129: "John Broome's script and Gil Kane's renderings debuted a character who would one day become a Green Lantern – Guy Gardner."

- ^ McAvennie "1960s" in Dolan, p. 103: "The Atom was the next Golden Age hero to receive a Silver Age makeover from writer Gardner Fox and artist Gil Kane."

- ^ Thomas, Roy (Autumn 1999). "Splitting the Atom". Alter Ego. 3 (2). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 12.

- ^ McAvennie "1960s" in Dolan, p. 119

- ^ McAvennie "1960s" in Dolan, p. 134: "Four years after the debut of Wonder Girl, writer Marv Wolfman and artist Gil Kane disclosed her origins."

- ^ While working for DC, Kane (and other artists) began to moonlight at Marvel, and needed to conceal their identities. See: Ro, Ronin. Tales to Astonish: Jack Kirby, Stan Lee and the American Comic Book Revolution, p. 92 (Bloomsbury, 2004); Scott Edward at the Grand Comics Database; and Evanier, Mark (April 14, 2008). "Why did some artists working for Marvel in the sixties use phony names?". P.O.V. Online (column). Archived from the original on November 26, 2009. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- ^ DeFalco, Tom; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2008). "1960s". Marvel Chronicle A Year by Year History. London, United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 121. ISBN 978-0756641238.

Stan Lee needed a villain who could stand up to the Hulk ... Working with artist Gil Kane, he proudly presented the Abomination.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Gil Kane". Lambiek Comiclopedia. December 14, 2007. Archived from the original on January 6, 2014.

- ^ Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1970s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. London, United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 55. ISBN 978-0756692360.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Manning "1970s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 56: Stan Lee skirted the system by tackling the controversial subject of drug abuse with the help of penciler Gil Kane.

- ^ Daniels, Les (1991). Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics. New York, New York: Harry N. Abrams. pp. 152 and 154. ISBN 9780810938212.

As a result of Marvel's successful stand, the Comics Code had begun to look just a little foolish. Some of its more ridiculous restrictions were abandoned because of Lee's decision.

- ^ Manning "1970s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 68: "This story by writer Gerry Conway and penciler Gil Kane would go down in history as one of the most memorable events of Spider-Man's life."

- ^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 138: "Rick Jones ... became bonded to Captain Mar-Vell thanks to Roy Thomas and artist Gil Kane."

- ^ Sanderson, Peter "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 156: "Adam Warlock received his own bimonthly comic book in August [1972], written by Roy Thomas and pencilled by Gil Kane."

- ^ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 165: "Marvel combined the superhero and martial arts genres when writer Roy Thomas and artist Gil Kane created Iron Fist in Marvel Premiere #15."

- ^ Manning "1970s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 59: "In the first issue of The Amazing Spider-Man to be written by someone other than Stan Lee ... Thomas also managed to introduce a major new player to Spidey's life – the scientifically created vampire known as Morbius."

- ^ Manning "1970s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 70: "The Man-Wolf, a major new threat to Spider-Man and his supporting cast, was introduced in a two-part tale that saw the werewolf terrorize J. Jonah Jameson."

- ^ Gerry Conway quoted in Buchanan, Bruce (October 2009). "Morbius the Living Vampire". Back Issue! (36). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 31.

- ^ Greenberger, Robert (2012). The Art of Howard Chaykin. Mount Laurel, New Jersey: Dynamite Entertainment. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-1606901694.

- ^ "Gil Kane on Jack Kirby". Jack Kirby Collector (21). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing. October 1998. Archived from the original on December 24, 2010. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

- ^ Cassell, Dewey (August 2006). "Talking About Tigra: From the Cat to Were-Woman". Back Issue! (17). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 26–33.

- ^ a b "Kane, Gil: American artist, Eli Katz". Encyclopædia Britannica Book of the Year, 2001. Britannica.com. Archived from the original on February 11, 2009. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- ^ a b Holland, Steve (February 3, 2000). "Gil Kane: Illustrator who revived America's comic heroes". The Guardian. London, United Kingdom. Archived from the original on March 17, 2013. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

- ^ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 179: "Writer Marv Wolfman and artists Gil Kane and Dave Cockrum produced John Carter, Warlord of Mars, based on another Edgar Rice Burroughs' character."

- ^ "Comic Book Creator #11 by TwoMorrows Publishing – Issuu". February 9, 2016.

- ^ "Jason Drum : Gil Kane".

- ^ Sanderson, Peter (September–October 1981). "Justice League #200 All-Star Affair". Comics Feature (12/13). New Media Publishing: 17.

- ^ Lantz, James Heath (October 2014). "Inner-Space Opera: A Look at Marvel's Micronauts Comics". Back Issue! (76). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 48.

- ^ Manning, Matthew K. "1980s" in Dolan, p. 202: "[Brainiac] got a complete wardrobe and powers makeover in this double-sized special ... writer Marv Wolfman and artist Gil Kane chronicled Brainiac's evolution into robot form."

- ^ Greenberger, Robert (August 2017). "It Sounded Like a Good Idea at the Time: A Look at the DC Challenge!". Back Issue! (98). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 37–38.

- ^ Martin, Brian (August 2017). "Where the Action is ... Weekly". Back Issue! (98). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 62.

- ^ Trumbull, John (October 2014). "Swords, Sorcery, and Size-Changing: Sword of the Atom". Back Issue! (76). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 33–39.

- ^ Manning "1990s" in Dolan, p. 275: " The behind-the-scenes talent on the monumental issue appropriately spanned several generations of the Man of Tomorrow's career. Written by Dan Jurgens, Karl Kesel, David Michelinie, Louise Simonson, and Roger Stern, the one-shot featured the pencils of John Byrne, Gil Kane, Stuart Immonen, Paul Ryan, Jon Bogdanove, Kieron Dwyer, Tom Grummett, Dick Giordano, Jim Mooney, Curt Swan, Nick Cardy, Al Plastino, Barry Kitson, Ron Frenz, and Dan Jurgens."

- ^ Greenberger (2012) p. 131: "Chaykin signed on to write a three-part Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight arc for DC in 1991, which marked his first work with Gil Kane since Chaykin apprenticed with him nearly 20 years earlier."

- ^ Greenberger (2012) p. 141: "Another Chaykin Elseworlds project arrived in 1998: Superman: Distant Fires, illustrated by Gil Kane and Kevin Nowlan."

- ^ Manning "1990s" in Dolan, p. 281: "Writers Mark Waid and Brian Augustyn, with illustrators Gil Kane, Joe Staton, and Tom Palmer, recounted the life and times of the Silver Age Flash Barry Allen in this ninety-six-page hardcover."

- ^ a b c Oliver, Myrna (February 2, 2000). "Gil Kane; Innovative Comic Book Artist". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 9, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Last Heroes [Ibooks]". bookinfo.com. Retrieved July 20, 2024.

- ^ Janulewicz, Tom (February 1, 2000). "Gil Kane, Space-Age Comic Book Artist, Dies". Space.com. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009.

- ^ "Bullpen Bulletins", Marvel Comics cover-dated December 1974.

- ^ "Artists Will Join 'Chalk Talk' to Open Stan Drake Exhibit" (PDF). The Wilton Bulletin. Wilton, Connecticut. March 25, 1981. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- ^ Friedman, Michael Jan (2002). In Darkest Night. New York, New York: Bantam Books. pp. 144. ISBN 978-0553487718.

- ^ "His Name Is... Kane" at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Levitz "The Silver Age 1956–1970", pp. 300–301: "It's said that many comics artists ... tend to draw characters that resemble themselves ... and here Kane is perfectly justified"

- ^ Marvel Visionaries Gil Kane. Marvel Comics. 2002. p. 256. ISBN 978-0785108887.

- ^ Adventures of Superman: Gil Kane. DC Comics. 2013. p. 392. ISBN 978-1401236748.

- ^ "CCI: IDW To Release Gil Kane's The Amazing Spider-Man Artist's Edition". Comic Book Resources. July 13, 2012. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Archive requires scrolldown

- ^ Gil Kane's the Amazing Spider-Man Artists Edition. IDW Publishing. 2012. ISBN 978-1613775257.

- ^ "NCS Awards > Division Awards". National Cartoonists Society. Archived from the original on April 18, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ^ "Inkpot Award Winners". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on July 9, 2012. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ Hahn, Joel (ed.). "1997 Will Eisner Comic Industry Award Nominees and Winners". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on November 2, 2010. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ^ Hahn, Joel (ed.). "1997 Harvey Award Nominees and Winners". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013.

Further reading

[edit]- Herman, Daniel (2001). Gil Kane: The Art of the Comics. Neshannock Township, Lawrence County, Pennsylvania: Hermes Press. ISBN 0-9710311-2-6.

- Herman, Daniel (2002). Gil Kane Art and Interviews. Neshannock, Pennsylvania: Hermes Press. ISBN 978-0-9710311-6-6.

External links

[edit]- Schenk, Ramon (ed.). "Gil Kane Index". Archived from the original on September 20, 2005.

- Gil Kane at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

- Gil Kane at IMDb

- Gil Kane Archived April 4, 2023, at the Wayback Machine at Mike's Amazing World of Comics

- Gil Kane at the Unofficial Handbook of Marvel Comics Creators

- 1926 births

- 2000 deaths

- American comics artists

- American comics writers

- United States Army personnel of World War II

- Artists from Brooklyn

- Deaths from cancer in Florida

- Golden Age comics creators

- Hanna-Barbera people

- High School of Art and Design alumni

- Inkpot Award winners

- Jewish American comics creators

- Latvian emigrants to the United States

- Latvian Jews

- Marvel Comics people

- People from Aventura, Florida

- People from Jericho, New York

- People from Wilton, Connecticut

- Silver Age comics creators

- United States Army soldiers

- Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame inductees

- DC Comics people

- Jews from New York (state)