Battle of Raphia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2011) |

| Battle of Raphia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Fourth Syrian War | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Ptolemaic Egypt | Seleucid Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Ptolemy IV | Antiochus III | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

75,000: 70,000 infantry, 5,000 cavalry, 73 elephants |

68,000: 62,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry, 102 elephants | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

2,200:

|

14,300:

| ||||||

The Battle of Raphia, also known as the Battle of Gaza,[citation needed] was fought on 22 June 217 BC near modern Rafah between the forces of Ptolemy IV Philopator, king and pharaoh of Ptolemaic Egypt and Antiochus III the Great of the Seleucid Empire during the Syrian Wars.[1] It was one of the largest battles of the Hellenistic kingdoms and of the ancient world, and determined the sovereignty of Coele Syria.

Prelude

[edit]The two largest Hellenistic kingdoms in the 3rd century BC, Ptolemaic Egypt and the Seleucid Empire, repeatedly fought for control of Syria in a series of conflicts known as the Syrian Wars. The Fourth Syrian War began in 219 BC, during which time Ptolemaic Egypt was ruled by Ptolemy IV, and the Seleucid Empire was ruled by Antiochus III the Great.

In 217 BC, both armies were on campaign through Syria. The Seleucid and Ptolemaic armies met near the small Syrian town of Rafah. Antiochus initially set up his camp at a distance of 10 (about 2 km) and then only 5 stades (about 1 km) from his adversary's. The battle began with a series of small skirmishes around the perimeter of each army. One night, Theodotus the Aetolian, formerly an officer of Ptolemy, sneaked inside the Ptolemaic camp and reached what he presumed to be the King's tent to assassinate him; but he was absent and the plot failed.

Forces

[edit]Seleucid Army

[edit]Antiochus' army was composed of 5,000 lightly armed Daae, Carmanians, and Cilicians under Byttacus the Macedonian, 10,000 Phalangites (the Argyraspides or Silver Shields) under Theodotus the Aetolian, the man who had betrayed Ptolemy and handed much of Coele Syria and Phoenicia over to Antiochus, 20,000 Macedonian Phalangites under Nicarchus and Theodotus Hemiolius, 2,000 Persian and Agrianian archers and slingers with 2,000 Thracians under Menedemus (Μενέδημος) of Alabanda, 5,000 Medes, Cissians, Cadusii, and Carmanians under the Aspasianus the Mede, 10,000 Arabians under Zabdibelus, 5,000 Greek mercenaries under Hippolochus the Thessalian, 1,500 Cretans under Eurylochus, 1,000 Neocretans under Zelys the Gortynian, and 500 Lydian javelineers and 1,000 Cardaces (Kardakes) under Lysimachus the Gaul.

Four thousand horsemen under Antipater, the nephew of the King and 2,000 under Themison formed the cavalry and 102 Indian war elephants marched under Philip and Myischos.

Ptolemaic Army

[edit]Ptolemy had just ended a major recruitment and retraining plan with the help of many mercenary generals. His forces consisted of 3,000 Hypaspists under Eurylochus the Magnesian (the Agema), 2,000 peltasts under Socrates the Boeotian, 25,000 Macedonian Phalangites under Andromachus the Aspendian and Ptolemy, the son of Thraseas, and 8,000 Greek mercenaries under Phoxidas the Achaean, and 2,000 Cretan under Cnopias of Allaria and 1,000 Neocretan archers under Philon the Cnossian. He had another 3,000 Libyans under Ammonius the Barcian and 20,000 Egyptians under his chief minister Sosibius trained in the Macedonian way. These Egyptians were trained to fight alongside the Macedonians. Apart from these he also employed 4,000 Thracians and Gauls from Egypt and another 2,000 from Europe under Dionysius the Thracian.[2]

His Household Cavalry (tis aulis) numbered 700 men and the local (egchorioi) and Libyan horse, another 2,300 men, had as appointed general Polycrates of Argos. Those from Greece and the mercenaries were led by Echecrates the Thessalian. Ptolemy's force was accompanied by 73 elephants of the African stock.

According to Polybius, Ptolemy had 70,000 infantry, 5,000 cavalry, and 73 war elephants and Antiochus 62,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry, and 102 elephants.[3]

War elephants

[edit]This is the only known battle in which African and Asian elephants were used against each other. Due to Polybius' descriptions of Antiochus' Asian elephants (Elephas maximus), brought from India, as being larger and stronger than Ptolemy's African elephants, it had once been theorized[4] that Ptolemy's elephants were in fact the African forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis), a close relative to the African bush elephant (Loxodonta africana) – a typical African bush elephant would tower over an Asian one, meaning that the smaller forest elephant would be a better fit with Polybius' descriptions. However recent DNA research[5] has revealed that most likely, Ptolemy's elephants were in fact Loxodonta africana, albeit culled from a population of more diminutive African bush elephants still found in Eritrea today. Another possibility is that Ptolemy utilized the now extinct North African elephants (Loxodonta africana pharaoensis).[6] Much smaller than their Indian or Bush cousins, members of this subspecies were typically around 8-foot (2.4 m) high at the shoulder.[7] Regardless of origin, according to Polybius, Ptolemy's African elephants could not bear the smell, sound, and sight of their Indian counterparts. The Indian's greater size and strength easily routed the Africans.

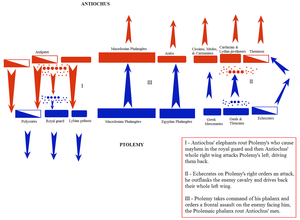

Battle

[edit]After five days of skirmishing, the two kings decided to array their troops for battle. Both placed their Phalangites in the center. Next to them they fielded the lightly armed and the mercenaries in front of which they placed their elephants and even further in the wings their cavalry. They spoke to their soldiers, took their places in the lines – Ptolemy in his left and Antiochus in his right wing – and the battle commenced.

In the beginning of the battle, the elephant contingents on the wings of both armies moved to charge. Ptolemy's diminutive African elephants retreated in panic before the impact with the larger Indians and ran through the lines of friendly infantry arrayed behind them, causing disorder in their ranks. At the same time, Antiochus had led his cavalry to the right, rode past the left wing of the Ptolemaic elephants charging the enemy horse. The Ptolemaic and Seleucid phalanxes then engaged. However, while Antiochus had the Argyraspides, Ptolemy's Macedonians were bolstered by the Egyptian phalanx. At the same time, the right wing of Ptolemy was retreating and wheeling to protect itself from the panicked elephants. Ptolemy rode to the center encouraging his phalanx to attack, Polybius tells us "with alacrity and spirit". The Ptolemaic and Seleucid phalanxes engaged in a stiff and chaotic fight. On the Ptolemaic far right, Ptolemy's cavalry was routing their opponents.

Antiochus routed the Ptolemaic horse posed against him and pursued the fleeing enemy en masse, believing to have won the day, but the Ptolemaic phalanxes eventually drove the Seleucid phalanxes back and soon Antiochus realized that his judgment was wrong. Antiochus tried to ride back, but by the time he rode back, his troops were routed and could no longer be regrouped. The battle had ended.

After the battle, Antiochus wanted to regroup and make camp outside the city of Raphia but most of his men had already found refuge inside and he was thus forced to enter it himself. Then he marched to Gaza and asked Ptolemy for the customary truce to bury the dead, which he was granted.

According to Polybius, the Seleucids suffered a little under 10,000 infantry dead, about 300 horse, and 5 elephants, and 4,000 men were taken prisoner. The Ptolemaic losses were 1,500 infantry, 700 horse, and 16 elephants. Most of the Ptolemies' elephants were captured by the Seleucids.[8]

Aftermath

[edit]Ptolemy's victory secured the province of Coele-Syria for Egypt, but it was only a respite; at the Battle of Panium in 200 BC Antiochus defeated the army of Ptolemy's young son, Ptolemy V Epiphanes and recaptured Coele Syria and Judea.

Ptolemy owed his victory in part to having a properly equipped and trained native Egyptian phalanx, which for the first time formed a large proportion of his phalangitis, thus ending his manpower problems. The self-confidence the Egyptians gained was credited by Polybius as one of the causes of the secession in 207–186 of Upper Egypt under pharaohs Hugronaphor and Ankhmakis, who created a separate kingdom that lasted nearly twenty years.

The battle of Raphia marked a turning-point in Ptolemaic history. The native Egyptian element in 2nd-century Ptolemaic administration and culture grew in influence, driven in part by Egyptians having played a major role in the battle and in part by the financial pressures on the state aggravated[9] by the cost of the war itself. The stele that recorded the convocation of priests at Memphis in November 217, to give thanks for the victory was inscribed in Greek and hieroglyphic and demotic Egyptian:[10] in it, for the first time, Ptolemy is given full pharaonic honours in the Greek as well as the Egyptian texts; subsequently this became the norm.[11]

Some biblical commentators see this battle as being the one referred to in Daniel 11:11, where it says, "Then the king of the South will march out in a rage and fight against the king of the North, who will raise a large army, but it will be defeated."[12]

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Battle of Raphia, 22 June 217". www.historyofwar.org. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ Bill Thayer (ed.). "The Histories of Polybius – Book 5". University of Chicago. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ Polybius V. 65 and V. 79–87.

- ^ Gowers, William (1948). "African Elephants and Ancient Authors". African Affairs. 47 (188): 173–180. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a093647. JSTOR 718306.

- ^ Brandt, Adam L.; Hagos, Yohannes; Yacob, Yohannes; David, Victor A.; Georgiadis, Nicholas J.; Shoshani, Jeheskel; Roca, Alfred L. (27 November 2013). "The Elephants of Gash-Barka, Eritrea: Nuclear and Mitochondrial Genetic Patterns". Journal of Heredity. 105 (1): 82–90. doi:10.1093/jhered/est078. ISSN 1465-7333. PMID 24285829.

- ^ "War elephant myths debunked by DNA". EurekAlert!. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014.

- ^ "War Elephant Myths Debunked by DNA | the Institute for Genomic Biology". Archived from the original on 14 January 2014. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Polybius, 5.86

- ^ The Ptolemaic currency had already been debased under Ptolemy V (F. W. Walbank, The Hellenistic World 1981:119.

- ^ Raphia Decree at attalus.org. See also the trilingual Decree of Memphis (Ptolemy IV) of ca 218.

- ^ As on the Rosetta stone. F. W. Walbank, The Hellenistic World 1981:119.

- ^ Jordan, James B. (2007). The Handwriting on the Wall: A Commentary on the Book of Daniel. American Vision. p. 553.

External links

[edit]- Raphia Decree – English translation by E.R.Bevan