John Simpson Kirkpatrick

John Simpson | |

|---|---|

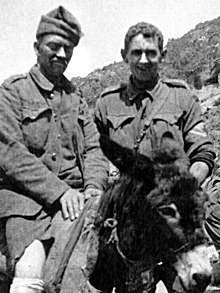

Simpson (right) with his donkey | |

| Birth name | John Kirkpatrick |

| Born | 6 July 1892 South Shields, England |

| Died | 19 May 1915 (aged 22) Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, Ottoman Turkey |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | Australia |

| Service | Australian Imperial Force |

| Years of service | 1914–1915 |

| Rank | Private |

| Service number | 202 |

| Unit | 3rd Field Ambulance |

| Battles / wars | |

| Awards | Mentioned in Despatches |

John Kirkpatrick (6 July 1892 – 19 May 1915), commonly known as John Simpson, was a stretcher bearer with the 3rd Australian Field Ambulance during the Gallipoli campaign – the Allied attempt to capture Constantinople, capital of the Ottoman Empire, during the First World War.

After the landing at Anzac Cove on 25 April 1915, Simpson used donkeys to provide first aid and carry wounded soldiers to the beach, from where they could be evacuated. He continued this work for three and a half weeks – often under fire – until he was killed by machine-gun fire during the third attack on Anzac Cove. Simpson and his donkey have become part of the Anzac legend.

Early life

[edit]Simpson was born on 6 July 1892 in Eldon Street, Tyne Dock, South Shields,[1] County Durham, England, to Scottish parents: Sarah Kirkpatrick (née Simpson) and Robert Kirkpatrick.[2][3][4] He was one of eight children, and worked with donkeys as a youth, during summer holidays.[2] He attended Barnes Road Junior School and later Mortimer Road Senior School.[5]

At 16, he volunteered to train as a gunner in the Territorial Force, as British Army reserve units were known at the time,[6] and in early 1909 he joined the British merchant navy.[7]

In May 1910, Simpson deserted his ship at Newcastle, New South Wales, and travelled widely in Australia, taking on various jobs, such as cane-cutting in Queensland and coal mining in the Illawarra district of New South Wales. In the three or so years leading up to the outbreak of the First World War, he worked as a steward, stoker and greaser on Australian coastal ships.[8]

Simpson held, or developed, left wing political views while he worked in Australia, and wrote in a letter to his mother: "I often wonder when the working men of England will wake up and see things as other people see them. What they want in England is a good revolution and that will clear some of these Millionaires and lords and Dukes out of it and then with a Labour Government they will almost be able to make their own conditions."[9] According to former union leader Alf Rankin, there is anecdotal evidence that Simpson belonged to the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or "Wobblies"), a radical international labour union, although that has never been confirmed by historical documents or other sources.[10]

Military service

[edit]Simpson enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force after the outbreak of war, apparently as a means of returning to England.[3] He enlisted as "John Simpson", and may have dropped his real surname to avoid being identified as a ship deserter.[2] Simpson enlisted as a field ambulance stretcher bearer, a role only given to physically strong men, on 23 August 1914 at Swan Barracks, Francis Street, in Perth,[2] and undertook training at Blackboy Hill Training Camp.[11] He was assigned to the 3rd Australian Field Ambulance and the regimental number 202.[12]

Simpson landed on the Gallipoli Peninsula on 25 April 1915 with the 3rd Field Ambulance as part of the 1st Australian Division.[2] In the early hours of the following day, as he was bearing a wounded comrade on his shoulders, he spotted a donkey and quickly began making use of it to carry his fellow soldiers.[2] Simpson would sing and whistle, seeming to ignore the bullets flying through the air, while he tended to his comrades.[2]

He used at least five different donkeys, known as "Duffy No. 1", "Duffy No. 2", "Murphy", "Queen Elizabeth" and "Abdul" at Gallipoli; some of the donkeys were killed and/or wounded in action.[13][8][14][15] He and the donkeys soon became a familiar sight to the Anzacs, many of whom knew Simpson by the nicknames such as "Scotty" (in reference to his ancestry) and "Simmy". Simpson himself was also sometimes referred to as "Murphy".[14] Other Anzac stretcher bearers began to emulate Simpson's use of the donkeys.[13]

Colonel (later General) John Monash wrote: "Private Simpson and his little beast earned the admiration of everyone at the upper end of the valley. They worked all day and night throughout the whole period since the landing, and the help rendered to the wounded was invaluable. Simpson knew no fear and moved unconcernedly amid shrapnel and rifle fire, steadily carrying out his self-imposed task day by day, and he frequently earned the applause of the personnel for his many fearless rescues of wounded men from areas subject to rifle and shrapnel fire."[2]

Other contemporary accounts of Simpson at Gallipoli speak of his bravery and invaluable service in bringing wounded down from the heights above Anzac Cove through Shrapnel and Monash gullies.[16] However, his donkey service spared him the even more dangerous and arduous work of hauling seriously wounded men back from the front lines on a stretcher.[17]

On 19 May 1915, during the Third attack on Anzac Cove, Simpson was killed by machine gun fire.[2][18]

Private Victor Laidlaw, with the 2nd Field Ambulance, wrote in his diary of Simpson's death:

Another fatality I found out today – was a private in the 1st Field Ambulance, he had been working between the base and the firing line bringing down wounded on a donkey, he had done invaluable service to our cause. One day he was bringing down a man from the trenches and coming down an incline he was shot right through the heart, it is regretted on all sides as this chap was noticed by all, and everybody got to know him, one couldn't miss him as he used to always work with his donkey, cheerful and willing, this man goes to his death as a soldier.[19][20]

He was survived by his mother and sister, who were still living in South Shields.[4] He was buried at the Beach Cemetery.[21]

Commemoration, depiction and myth

[edit]Conflation with Richard Henderson

[edit]

Soon after his death, Simpson was being conflated with at least one other stretcher bearer using a donkey around Anzac Cove, Richard Alexander Henderson, of the New Zealand Medical Corps (NZMC).[14][15] Henderson said later that he had taken over one of Simpson's donkeys, known as "Murphy".[14][15]

An iconic image (right) of Henderson, with a donkey at Gallipoli,[14][22] has often been wrongly assumed to portray John Simpson Kirkpatrick. The image originated in a photograph taken by Sergeant James G. Jackson of the NZMC on 12 May 1915 (a week before Simpson's death).[23] The image became famous after Horace Moore-Jones, a New Zealand artist, who had been a member of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force at Gallipoli,[24] painted at least six versions of it.[23] Following the death of Simpson, Henderson continued to rescue wounded soldiers from the battlefield and was later awarded the Military Medal.[25][26] Moore-Jones' paintings have usually been referred to by titles such as Private Simpson, D.C.M., & his donkey at Anzac and/or The Man with the Donkey. Many derivatives of the image, including sculptures, have appeared and a variation of it was included on three postage stamps issued in Australia in 1965 to mark the 50th anniversary of Gallipoli – on the five penny, eight penny and two shillings and three pence stamps.[27]

Growth of legend

[edit]The legend surrounding Simpson, sometimes under the misnomer "Murphy" grew largely from an account of his actions published in a 1916 book, Glorious Deeds of Australasians in the Great War. This was a wartime propaganda effort, and many of its stories of Simpson, supposedly rescuing 300 men and making dashes into no man's land to carry wounded out on his back, are demonstrably untrue. In fact, transporting that many men down to the beach in the three weeks that he was at Gallipoli would have been a physical impossibility, given the time the journey took.[28] However, the stories presented in the book were widely and uncritically accepted by many people, including the authors of some subsequent books on Simpson.[citation needed]

Popular culture

[edit]A silent film based on Simpson's exploits, Murphy of Anzac, was released in 1916.[12]

His life inspired the 1938 radio play The Man with the Donkey.[29]

In 1965, in the lead up to the fiftieth anniversary of Gallipoli, there were calls for a commemorative medal for veterans of the Gallipoli campaign and/or the award of a late Victoria Cross to Simpson. Both proposals were rejected by the Australian Federal Government in 1965. In January 1966, Robert Menzies who had been Prime Minister of Australia since 1949 retired and was replaced by Harold Holt. The new government soon announced that Australia would present to Australian Army and Royal Australian Navy veterans of the Gallipoli campaign in 1915, an Anzac Commemorative Medal. Both living veterans and next of kin of deceased veterans could apply for the medallion but only living veterans would receive a lapel badge. The first medallions were issued to Gallipoli veterans shortly before Anzac Day 1967.[30] The medallion and lapel badge featured Simpson and his donkey.[31] They were also portrayed on a series of Anzac postage stamps issued on 14 April 1965.[32]

In 1977, a donkey "joined" the Royal Australian Army Medical Corps, under the name "Jeremy Jeremiah Simpson", with the rank of Private and the regimental number MA 0090. In 1986, this particular donkey was permanently adopted as the official mascot of the corps.[33]

Simpson featured in an episode of the television show Michael Willessee's Australians called "Private John Simpson" in 1988.[34] [35]

At least two songs have been written about him: "John Simpson Kirkpatrick" by Issy and David Emeney with Kate Riaz, on the album Legends and Lovers,[36] and "Jackie and Murphy" by Martin Simpson on the album Vagrant Stanzas.[37]

The Australian RSPCA, in May 1997 posthumously awarded its Purple Cross to the donkey Murphy for performing outstanding acts of bravery towards humans.[38]

In 2011, a play by Valerie Laws entitled The Man and the Donkey premiered at the Customs House in South Shields.[39] The part of John Simpson Kirkpatrick was played by local actor Jamie Brown.[40]

On 19 May 2015, the Australian High Commissioner, Alexander Downer, visited South Shields as part of special celebrations marking 100 years to the day that John Simpson Kirkpatrick was killed in action.[41]

Campaign to award Simpson the Victoria Cross

[edit]There have been several petitions over the decades to have Simpson awarded a Victoria Cross (VC) or a Victoria Cross for Australia.[42] There is a persistent myth that he was recommended for a VC, but that this was either refused or mishandled by the military bureaucracy. However, there is no documentary evidence that such a recommendation was ever made.[43] The case for Simpson being awarded a VC is based on diary entries by his commanding officer that express the hope he would receive either a Distinguished Conduct Medal or VC. However, the officer in question never made a formal recommendation for either of these medals.[12] Simpson's Mention in Despatches was consistent with the recognition given to other men who performed the same role at Gallipoli.[44]

In April 2011, the Australian Government announced that Simpson would be one of thirteen servicemen examined in an inquiry into "Unresolved Recognition for Past Acts of Naval and Military Gallantry and Valour".[45] The tribunal for this inquiry was directed to make recommendations on the awarding of decorations, including the Victoria Cross. Concluding its investigations in February 2013, the tribunal recommended that no further award be made to Simpson, since his "initiative and bravery were representative of all other stretcher-bearers of 3rd Field Ambulance, and that bravery was appropriately recognised as such by the award of an MID."[44][46]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Pearn, John H. (21 April 2003). "An Anzac's childhood: John Simpson Kirkpatrick (1892–1915)" (PDF). Medical Journal of Australia. 178 (8). semanticscholar: 400–402. doi:10.5694/J.1326-5377.2003.TB05259.X. PMID 12697013. S2CID 45873058. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i ANZACS.net: Simpson – Australia's favourite hero (c. 2010). Retrieved on 19 June 2010.

- ^ a b Australian War Memorial: Simpson and his donkey (2010). Retrieved on 18 June 2010.

- ^ a b Australian War Memorial: Roll of Honour – John Simpson Kirkpatrick (2010). Retrieved on 18 June 2010.

- ^ Jim Mulholland (2015) John Simpson Kirkpatrick: The Untold Story of the Gallipoli Hero's Early Life

- ^ Wilson, G. Dust Donkeys and Delusions: The Myth of Simpson and His Donkey Exposed

- ^ Tribunal Report. Chapter 15 p160.

- ^ a b Walsh, G.P. "Kirkpatrick, John Simpson (1892–1915)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ^ Humphrey McQueen, 2004, Social Sketches of Australia, St Lucia, Qld; University of Queensland Press, p. 76.

- ^ "The 'real story' of unionist, anti war Gallipoli martyr Kirkpatrick aka Simpson and his Donkey". Sydney Alternative Media. 14 January 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ "Anzac Day 2016: WWI hero Simpson's will discovered by WA State Records Office". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 22 April 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ a b c "Chapter 15: Private John Simpson Kirkpatrick" (PDF). The Report of the Inquiry into Unresolved Recognition for Past Acts of Naval and Military Gallantry and Valour. Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ^ a b Peter Cochrane, 2014, Simpson and the Donkey: Anniversary Edition: the Making of a Legend, Carlton, Vic.; Melbourne University Publishing, pp. 56, 67, 152–3, 159.

- ^ a b c d e "Man with donkey not Australian". The Argus (Melbourne). 17 April 1950. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ a b c Walker Books: Simpson and His Donkey Archived 5 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine (27 May 2009). Retrieved on 25 June 2010.

- ^ "Murphy of Anzac". Cairns Post (Qld.: 1909–1954). Qld.: National Library of Australia. 30 January 1919. p. 2. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^ Cochrane, P. (1992). Simpson and the Donkey: The Making of a Legend. Burwood, Australia: Melbourne University Press.

- ^ "Private John Simpson Kirkpatrick". www.awm.gov.au. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ Laidlaw, Private Victor. "Diaries of Private Victor Rupert Laidlaw, 1914–1984 [manuscript] ". State Library of Victoria. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Cochrane, Peter (2014). Simpson and his donkey. Carlton: MUP.

Author notes that Laidlaw had misidentified Simpson as being attached to 1st rather than the correct 3rd Field Ambulance

- ^ "Simpson, John". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "The Man With The Donkey". New Zealand RSA. Archived from the original on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ^ a b P03136.001 (description of photograph), Australian War Memorial. Retrieved March 2013.

- ^ Gray, Anne (1 September 2010). "Moore-Jones, Horace Millichamp – Biography". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ "Anzac Heirs: A selfless lifetime of service – A picture of bravery". NZ Herald. New Zealand Herald. 22 April 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ "About Richard Henderson. The Man with the Donkey". NZ Returned and Services Association. Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ "50th Anniversary of Gallipoli Landings". PreDecimal Stamps of Australia. 14 April 1965. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ Wilson, G. (2006). "The Donkey Vote: A VC for Simpson – The case against". Sabretache: The Journal and Proceedings of the Military Historical Society of Australia. 47 (4): 25–37.

- ^ Australasian Radio Relay League. (1 April 1938), "RADIO PLAYS FOR APRIL", The Wireless Weekly: The Hundred per Cent Australian Radio Journal, 31 (13), Sydney: Wireless Press, nla.obj-712298226, retrieved 6 November 2023 – via Trove

- ^ Clive Johnson. Australians awarded: a comprehensive reference for military and civilian awards, decorations and medals to Australians since 1772 (2nd Edition), Renniks Publications, April 2014, 1SBN 978 0 9873386 3 1, p. 678

- ^ Baker, Mark (6 March 2013). "Taken for a ride?". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ Pearn, John and Bronwyn Wales. "How We Licked Them: The Role of the Philatelic Medium" (PDF). Journal of the Royal Historical Society. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ "RAAMC Customs, Traditions and Symbols". Royal Australian Army Medical Corps. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ "Michael Willesee's Australians". Australian Television Information Archive. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ^ Hooks, Barbara (8 March 1988). "History can't excuse but it can explain". The Age. p. 14.

- ^ "Legends & Lovers by Issy & David Emeney with Kate Riaz". Wild Goose Records. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ^ Denselow, Robin (26 July 2013). "Martin Simpson: Vagrant Stanzas – Review". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ^ "Donkey Activities". Donkey Society of Queensland. 29 August 2012. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ "Writer's Plea to Remember Hero". Shields Gazette. 11 February 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ "Man and the Donkey". Tyne Tees Television. 11 February 2011. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ^ "South Shields pays tribute to Man with the Donkey". Shields Gazette. 19 May 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ^ AAP (19 May 2008). "Anzac legend Simpson to miss out on VC". The West Australian. Archived from the original on 19 September 2006. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- ^ Australian Department of Defence (November 2007). "Defence Honours and Awards" (PDF). Australian Department of Defence. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ^ a b Valour Archived 7 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine at Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal. Retrieved on 2 March 2013.

- ^ Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal (April 2011). "Inquiry into Unresolved Recognition for Past Acts of Naval and Military Gallantry and Valour: Terms of Reference" (PDF). Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 April 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- ^ 'Fog of war' blamed for VC denials at The Telegraph

References

[edit]- Books

- Adam-Smith, P. (1978): The ANZACs. Penguin Books. (ISBN 0-7343-0461-7)

- Buley, E. C. (1916): Glorious Deeds of Australasians in the Great War. London: Andrew Melrose.

- Cochrane, P. (1992): Simpson and the Donkey: The Making of a Legend. Burwood, Australia: Melbourne University Press.

- Cochrane, P. (2014): Simpson and the Donkey Anniversary Edition: The Making of a Legend. Carlton, Vic.; Melbourne University Publishing.

- Curran, T. (1994): Across the Bar: The Story of "Simpson", the Man with the Donkey: Australia and Tyneside's great military hero. Yeronga: Ogmios Publications.

- Greenwood, M. (2008): Simpson and his Donkey. Australia: Walker Books. (ISBN 978-1-9211-5018-0)

- Mulholland, J. (2015): John Simpson Kirkpatrick The Untold Story of the Gallipoli Hero's Early Life. Alkali Publishing.

External links

[edit]- Australian War Memorial page on Simpson (and see also AWM biographical data and Roll of Honour data)

- Digger History page on Simpson with many images and information on New Zealander Richard Henderson, and his donkey.

- "Simpson: Hero or Myth?" – article by Kitty-Mae Carver, edited for publication by Robert Brokenmouth.

- National Archives – First Australian Imperial Forces personnel dossiers – Service Records Archived 26 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine and Pay Records[permanent dead link]

- John Simpson Kirkpatrick, A true ANZAC hero. – includes quotes of recollections of Kirkpatrick during his service and several digitised images.

- 1892 births

- 1915 deaths

- Anglo-Scots

- Australian Army soldiers

- Australian folklore

- Australian military personnel killed in World War I

- Australian people of English descent

- Australian people of Scottish descent

- People of the Gallipoli campaign

- Australian pacifists

- Combat medics

- People from South Shields

- British Merchant Navy personnel

- Burials at Beach Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemetery

- Military personnel from Tyne and Wear

- 20th-century British Army personnel

- British Army soldiers

- Territorial Force soldiers